In 2001, the same year Britney and Justin donned double denim and Harry Potter went to Hogwarts, Hedwig—the East German drag queen on a revenge tour across the Midwest —and her so-called “angry inch” siren sang their way into cult film history as a rock opera masterpiece with an unapologetically queer protagonist. But twenty years on, even with its continued relevance in shows like Sex Education, the cult phenomenon of Hedwig & the Angry Inch has aged…poorly. With the increasing visibility and amplification of trans stories and voices, the eponymous Hedwig—a character created by cis gay theatremaker John Cameron Mitchell—has fallen from grace as a cult hero. Today, Hedwig reads as a cringeworthy symbol of the fears cis gay men have about their proximity to trans people under the heteronormative gaze.

In the wake of controversy after casting controversy, and cisgender actors winning awards for playing transgender roles, Hedwig—for all her depth and humanity—is still a genderqueer character imagined and played by a cisgender man. Her backstory is, at its core, the nightmare cis people imagine trans identity to be. Hedwig begins her story as Hansel, a femme twink in East Berlin obsessed with queer rock icons David Bowie and Iggy Pop. When dashing US GI Luther seduces him with a literal trail of candy, they decide to marry to help Hansel escape to the West—on one horrific condition: Hansel must undergo gender affirmation surgery to pass the full medical exam apparently necessary to marry a foreigner. In keeping with the perverse cis obsession with transition surgery, the operation is botched—leaving Hansel with the film’s titular “angry inch.” Their marriage doesn’t last long; Luther, conspicuously the only Black or explicitly bisexual character in the film, is a remorseless philanderer, leaving his wife Hedwig for a younger, hotter, uncastrated twink—a tired and damaging stereotype of both Black men and of bisexuality that persists to this day, even within the queer community.

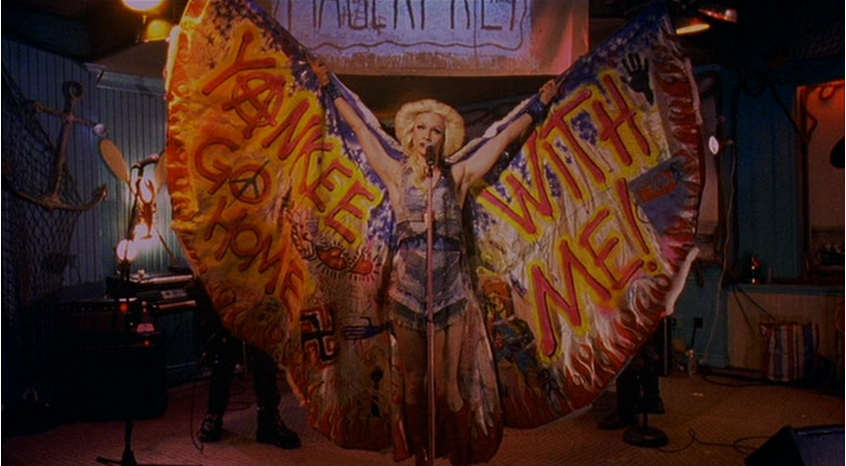

Mitchell himself admits that Hedwig is “a boy…forced into an uncomfortable gender reassignment that he never wanted.” Truthfully, Hedwig’s story is not a trans story at all, but the story of a gay man’s fears of being emasculated in a society that already mocks and scorns him for his perceived femininity. These fears—though valid—turn sour when they are used to weaponise the identities of actual trans women, who have been shunned from being the public faces of the LGBTQIA+ liberation movement they started. Hedwig, much like Jared Leto’s Rayon in Dallas Buyers Club, fulfills nearly every stereotype Hollywood has deemed necessary of a trans woman’s experience. Obsessive about her costumes and clothing, she screams at an ostensibly cis man for putting a bra in a laundromat dryer. She is self-absorbed and catty to the point of emotional abuse, holding her husband Yitzhak hostage by tearing his passport to pieces when he gets an opportunity beyond being her backup singer. After her chosen family and support network, her band, splits—a direct reaction to her treatment of Yitzhak—she turns to sex work. Hedwig struggles with substance abuse and a pervasive sense of victimhood, drunkenly slurring the story of how a teenage boy she molested stole her songs to build his successful music career as a rockstar. The climax of her substance abuse is realised when she crashes a car while driving drunk with him when they briefly reunite.

The next time Hedwig seeks out a lover, he is uncomfortably younger, and the audience is reminded of oblique references to Hedwig herself potentially having been molested by her father in childhood. These references to molestation—both implied and explicit —rely upon longstanding falsehoods linking sexual abuse to queerness, and queerness to pedophilia. Young Tommy is still straight, however, and this is made abundantly clear when he follows in the well-established tradition of straight men’s horror at discovering the absence of a vulva on someone he’s had sexual contact with.

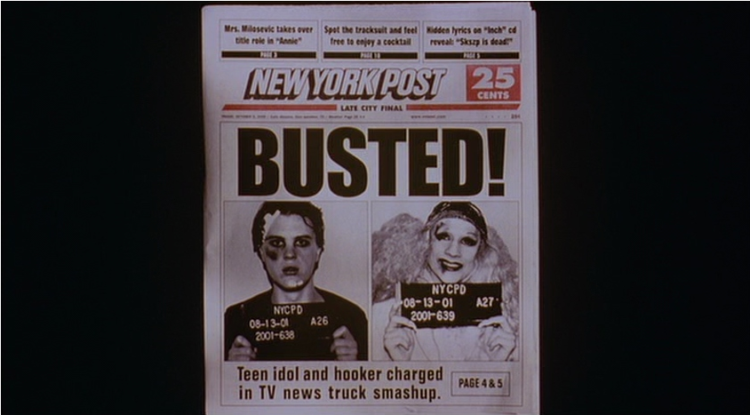

The final moments of the film are rife with additional problematic power dynamics. Hedwig gains the success she has always felt she deserved from the salaciousness of her tabloid story with Tommy, rather than suffering any of the very real violence trans women, particularly trans women of colour, experience when they are outed in the public eye. In a mix of rage and triumph, she strips off every last vestige of femininity until she is naked, returning to and embracing the public presentation of masculinity that was stolen in her—his—youth.

While it cannot and should not be denied that Hedwig & the Angry Inch broke barriers for representations of gender nonconformity in film, it is by no means the kind of representation trans—or even queer—people deserve. Hedwig triumphantly stripping away her femininity is a devastating rejection of a trans identity and an easy trigger for dysphoria for transfeminine viewers. Blackness and bisexuality exist only in promiscuity and betrayal. Relatively recent television shows like Orange is the New Black and Pose have catapulted trans women of colour into the spotlight on their own terms, with far more sensitive portrayals of trans life that exist outside the limited boxes of trauma, antisocial behaviours, and societal disgust. Hedwig & and the Angry Inch, for all its challenging of gender normativity, is framed through the uncompromising glare of the cis lens—and that just doesn’t cut it anymore. Trans people have always had the voice to tell their own stories, and now, twenty years after the film’s premiere, they are gaining the platform to do just that—without the need for such a car crash.

[Disclaimer on pronouns: The creator of Hedwig uses both masculine and feminine pronouns to describe the character at various points in their gender journey. That usage is reflected in the writing of this article.]