For as long as subcultures have existed, fashion and art have looted them for cultural cachet, edge and originality, bringing concepts that once lived in the dark to light. BDSM is no exception — but is this so-called “alternative sexuality” finally becoming better understood?

From goth and punk, to new romantics and grunge, the darker selvedges of society have long been used as fertile ground for artistic and sartorial inspiration, ultimately packaged and sold on the high street or featured on the big screen, the following season. The assimilation of subcultural elements into a mass produced aesthetic allows consumers to indulge their “dark sides” superficially, without fully committing to a lifestyle, enabling them to adopt a shed-able persona for just one day or night.

However, this quick access to fashion and entertainment also means it’s easy for consumers to ignore the origins of the styles they’re wearing or features they’re watching. One subculture that fashion consistently borrows from in order to inject not only edge but a sense of risqué sexuality to its collections is BDSM — or bondage and discipline, domination and submission, sadism and masochism, to give it its full name. From latex dresses to studded dog collars, fashion’s love affair with bondage is no secret, but the way it borrows artefacts from this subculture, divesting it of its explicitly sexual context, means the lifestyle from which it’s taken remains dangerously misrepresented and widely misunderstood.

Subcultural Stigma

From Kim Kardashian’s latex phase to the classic Rihanna chorus, “whips and chains excite me,” to the full blown mania of Fifty Shades of Grey, the incorporation of BDSM elements in pop culture is, by now, a well-established phenomenon. Perhaps not as shocking as it once was, often now it’s used as a quick fix for edge and heightened sexuality, a kind of aesthetic seasoning, without the consumer in question having to openly profess to — and therefore avoid the stigma of — BDSM proclivities. However, the truth is that, for actual practitioners of BDSM sex, all the gear, apparel and toys are more a function of the sexuality, in service to pleasure itself, than vice versa. BDSM amounts to far more than simply donning a gag or picking up a paddle. That isn’t the turn on; the turn on is the specific mindset of submission or dominance (or being a “top” or “bottom”) that goes along with such acts, pointing to far deeper psychological roots for those who find bondage and discipline pleasurable.

For those in the community, such preferences are not something that can simply be adopted for one night and walked away from in the morning. In her paper on “BDSM Sexuality in the San Francisco Bay Area”, cultural anthropologist Margot Weiss found that BDSM — while not as inherent to their identity as sexual orientation (e.g. gay, straight, bi, etc.) — formed a key part of her subjects’ sense of self, with the practice being viewed by participants as a combination of work, community and leisure pursuit.

Like many subcultures that are considered dark or perverse, BDSM has a long and storied history of stigmatisation and discrimination. Indulgence in BDSM activities was once a potent taboo; until 2010 even, BDSM was classed as a mental illness, with voluntary submission to beating, binding, or other “alternate sexual expressions” being defined and diagnosed in the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. There was no distinction drawn between sexual sadism practised on a non-consenting partner, and sadism and masochism undertaken by consenting, enthusiastic adults. An interest in BDSM could even be used, in court, as a reason to remove a parent’s custody of their child. Even following its pathologic declassification, such assumptions about the psychology of fetishists and polyamorists endure. Commonly held beliefs include the notion that there exists a markedly higher prevalence of childhood trauma in those who have BDSM preferences or that kink stems from severe mental disorder of maladjustment. This stigma is only doubled when an individual also belongs to the LGBTQ community or is a person of colour.

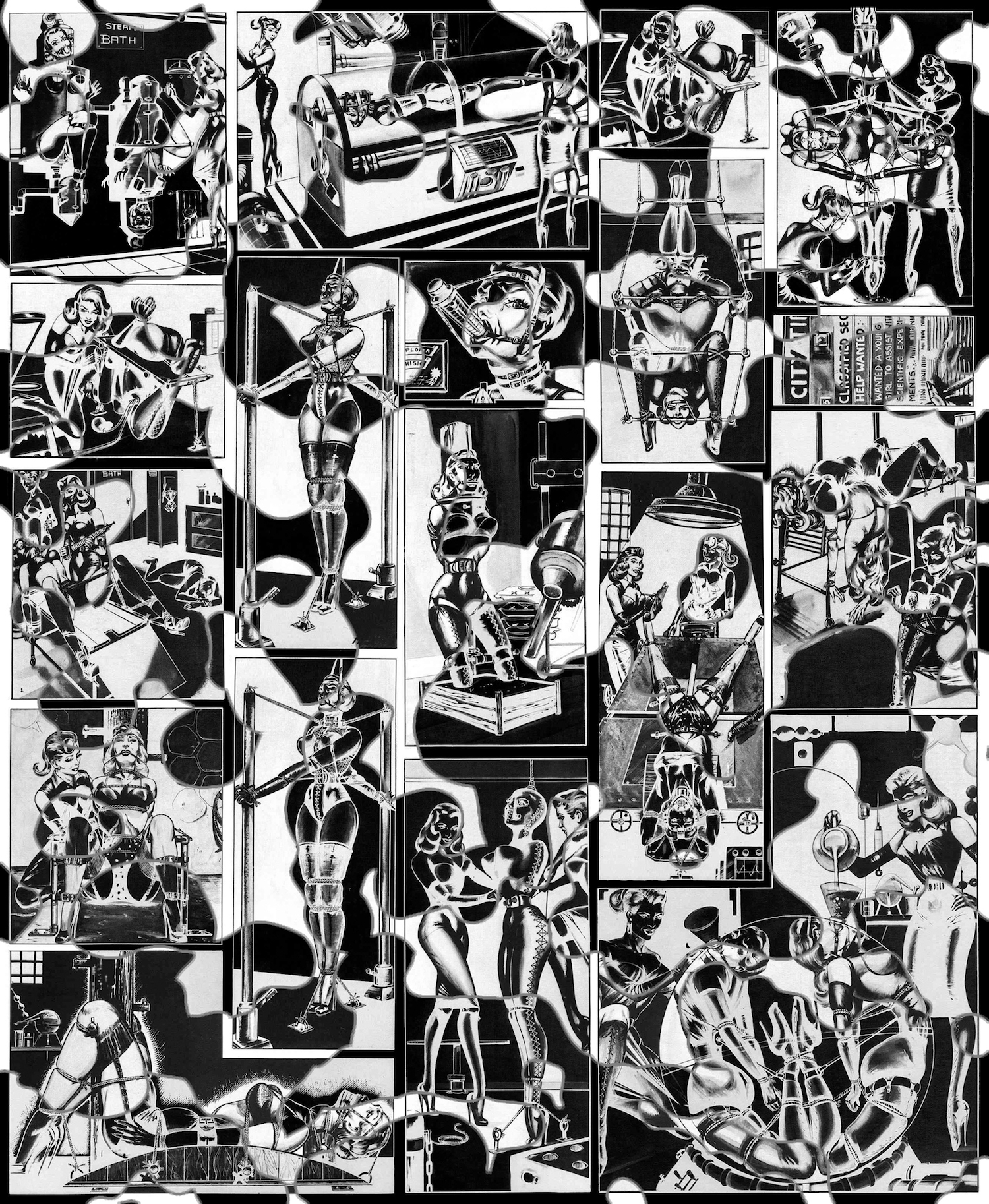

Captives Of The Scientists, 1950, Published by fetish art pioneer, Irving Klaw (1910 –1966)

However, in recent studies carried out in Australia and Holland, researchers found that there was no positive correlation between an interest in BDSM and mental distress. In fact, those who identified as belonging to the BDSM community enjoyed a greater sense of wellbeing than those in the “normal” control group. Subs and doms enjoyed an “altered state of consciousness” during play, resulting in a reduction in psychological stress after a session. Furthermore, an interest in BDSM tends to correlate to a high level of education, a higher-than-average income and greater open mindedness. The latter trait is perhaps self-explanatory; the former two may likely be linked to the high cost level associated in fully indulging a BDSM lifestyle, or participating in an organised community. Still, such facts paint a vastly different picture of bondage and discipline than the average stereotype of deviant, delinquent perverts who seek psychopathic debasement. It was for this reason precisely that BDSM was introduced as the preferred acronym to SM (sadism and masochism), which placed too high an emphasis on pain, obscuring the broader psychosexual appeal of BDSM activities.

Play as Political

Given the strictly taboo nature of BDSM — the dark secrecy that shrouded the practice for decades — it’s no surprise that its artefacts have been incorporated into art and fashion historically as a shocking, political statement. Think Robert Mapplethorpe’s sexually charged portraits, or Vivienne Westwood’s tartan bondage trousers; her shop SEX on the King’s Road in Chelsea peddled authentic rubberwear alongside her designs and Malcolm McLaren’s records when it originally opened.

Similarly, within the community itself, BDSM is not viewed simply as hedonistic pleasure. Professor Robin Bauer, in a paper surveying BDSM practices in the dyke+ bondage community across Europe and the States, found that, while the majority of his subjects reported partaking in bondage play for pleasure primarily, there was also a distinctly political lens applied to such acts and organisations. In queer circles, fantasy and play were safe spaces or “playgrounds” to “fuck with your gender”, allowing participants to explore the full spectrum of their masculinity and femininity, or lack thereof. Everything from age, gender and class was swapped and troubled in role play, with certain modes of play creating the chance to rename or reassign body parts in line with people’s inner gender orientations; for example, lesbian’s dildos were commonly referred to as “dicks”, or transmen’s vaginas referred to as “boy cunts”. In each case, such nomination positively contributed to practitioners’ views of their own bodies, allowing them to reconceptualise the body and reject the idea that biology is absolute in denominating sex and gender.

https://www.instagram.com/p/BeYvqx0ARm3/

Fashionable Fetish

Given the wide misrepresentation and stigma that BDSM is faced with, it can feel inauthentic at best, dangerous at worst, for the subculture to be trawled to pump life into mainstream fashion and culture. When transmuted into consumable, popular parts, subcultures tend to be strained through damaging norms, like heteronormativity, white privilege and sexism. Would Fifty Shades of Grey, for example, have been so popular if it didn’t regurgitate sexist power dynamics (which were widely decried by BDSM practitioners as misrepresentative of a healthy sub-dom relationship), and portray an affluent young straight white couple? It amounts to the age-old debate of appreciation versus appropriation. Do people buying PVC skirts and whips for Halloween costumes truly appreciate the positive, pleasurable connotations of BDSM, or are they using references to the culture specifically to highlight its perversion? Is it alright for someone to adopt aspects of the practice to appear edgy, only to be able to shed it the next day, when authentic BDSM practitioners have faced discrimination and stigmatisation for their preferences for years?

However, the creeping incorporation of BDSM aesthetics and references in fashion and pop culture, while perhaps diluting the potent sexuality of the practice, may in fact point to wider acceptance of it. In one 2015 study run by researcher Christian Joyal, called “What Exactly is an Unusual Sexual Fantasy?”, over 60% of both men and women had had fantasies about sexual submission or domination. In another 2017 study of the Belgian population, researchers found that 47% of people surveyed had performed at least one BDSM-related activity, with an additional 22% reporting to have had fantasies about it. The conclusion was a strong argument against the stigmatisation and pathologic characterisation of BDSM given its significant prevalence in the general population; that the findings signified BDSM was a “leisurely preference rather than a psychiatric affliction.” Given these findings, perhaps it’s fair to say that wider cultural visibility of BDSM is simply a reflection of reduced prudishness, or a heightened awareness that marital, heterosexual “vanilla” sex is not the only mode of play available — and, with proper education and boundaries established, a signal to society to let all your Secretary-inspired fantasies run free.

Taken from INDIE NO 61, THE DARK ISSUE – get your copy here.

Header image: Rihanna S&M (still) 2010 The Island Def Jam Music Group