In 2019, keeping things IRL is tricky. Circulating magazine content—including more sleek mainstream matter—hinges upon Instagram algorithms and influence. Yet, perhaps now more than ever before, real life ink-on-fingers zine culture is on the rise—paper cuts and all. And thankfully, the underground spirit from which zine culture was birthed is alive and well in the form of zine fairs, artist collectives, and the resolutely radical content that they put into circulation.

A few decades ago, the ‘anarchic’ side of zine making was thought to be the hand-drawn punk and riot grrrl publications from the ’70s to the ’90s. But, from the very birth of the first zine—a sci-fi fan publication from the 1930s—self-publishing has been a radical act, and the contemporary scene has come to reflect this attitude. DIY radicalism now comes in limitless forms—content that’s subversive, political, aesthetically divergent, champions anarchistic inclusivity, or is just plain weird. Even the more established magazines of our generation have begun to resemble radical modes (take the latest ‘copycat’ issue of A-lister approved Buffalo zine, which ripped off famous front cover layouts from other magazines.) Whilst this idea resembles a specific Japanese self-publishing movement Doujinshi—in which Japanese artists radically remix official content for underground manga—the revolutionary approaches the publishing world is beginning to employ are growing more diverse by the day.

Whether it’s through CTRL+C content contesting copyright laws, or wholly original art, the world of radical publishing is primed for a renaissance. So dive in as we forecast the future of DIY-til-you-die through 5 game-changing indie mags, whilst revealing the crème de la crème of the 2019 zine scene.

DIZZY

Unpretentious and New York to the bone, Dizzy is the magazine rejecting enforced glossiness to embrace scrapbook inclusivity. Creators Milah Libin and Arvid Logan describe their bi-annual brainchild as part “zine, periodical and art book” that “bridges the gap between artists of different ages, backgrounds, and levels of exposure.” An MO of inclusive accessibility has sparked a joyous exit from the confines of a traditional art book. Their content ranges from graffiti-esque collages, to segments written by New York rappers like Wiki, “formal interviews”, and a “Pet Page”—“to engage readers of all ages”, the two explain. Circulating art for everyone, by everyone—under 12s included—the magazine is a tangible treasure trove of high and low brow art.

“We like the idea of Dizzy being an archive; something that you can collect and reference years later. We remember going to St. Marks Bookstore and sifting through the magazine racks, finding publications like Mass Appeal and Drop Dead Magazine; publications covering topics that wouldn’t make it to the mainstream. We still have these magazines and zines.”

Dizzy‘s identity as an ‘accessible archive’, and their low, $15 price point proposes a joyous model for the future of zines. Maybe the internet has made underground art accessible, but Dizzy makes it collectible, built for anyone’s bedroom wall or backpack. In the words of Libin and Logan, once printed matter “is in your hands”, “it becomes yours and only yours”—Dizzy reminds us that the art world belongs to us too.

FRUITCAKE

Founded as “a direct result of the transphobic media that has been circulating across the world over the past years”, FRUITCAKE is the queer publication spearheading real political change. Whilst many contemporary zines might suffer from the insular nature of community-led printing, each issue theme of this mag is politically outward-looking and “tailored towards an activist stance”, FRUITCAKE explain. As an IRL object, the magazine is beautiful, painting categorically queer stories and journeys with jaw-dropping aesthetics and intimate flourishes. However, alongside the activist activities of its editor in chief Jamie Windust—who recently created a viral petition for more gender options on legal documents—FRUITCAKE is equal parts radiant and revolutionary:

“I think it’s important for FRUITCAKE to be political, and radical, due to the fact that our identities are politicised socially, therefore often we aren’t given the choice as to whether or not we allow our identities to be political. Our rights and access to services across the world are used as political pawns, so it’s empowering to reclaim that political power over our identities and more specifically, our stories.”

LGBTQIA+ rights have long been subject to both violation and capitalist commercialisation. FRUITCAKE is here to usher in a new era in print media—led by queer voices and issues—in which magazines can be unapologetically political, and personal all at once.

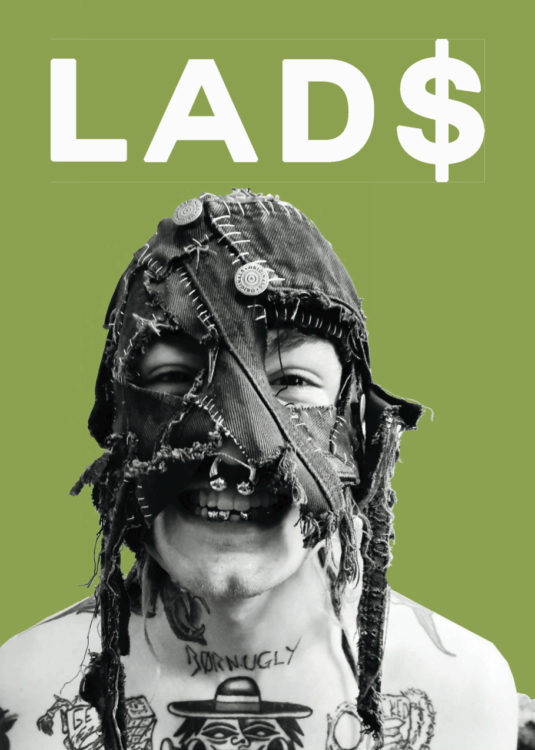

LAD$

After witnessing first-hand how the punk scene ostracised women, trans and non-binary people, a group of self-proclaimed activists, squatters, punks, and feminists formed LAD$. Based across the UK, this anarchistic and abrasive, yet endlessly artistic zine was birthed with visibility in mind—“to empower each other,” the founders explain. Empowering is certainly one way to describe LAD$—its pages drip with a raw, rallying energy that eschews the idea of ‘quiet’ progress. Instead of simulating a safe space, LAD$ feature “non-sugar coated real-life experiences… we encourage our readers and contributors to not be scared of engaging in discussion about difficult, sensitive issues,” they profess. If LAD$‘ defiant upheaval of the underground reminds you of riot grrrl—an earlier iteration of feminist, punk zine-making—you wouldn’t be the only one. But this collective is here to do better than their predecessors:

“One of the legitimate criticisms of riot grrrl was that it wasn’t inclusive enough (primarily focused on white middle-class cis-gendered women) and that it created this rather separatist ‘girls to the front’ approach. We prefer to seize the space that is rightfully ours, rather than to create an alternative that excludes people.”

Whilst LAD$‘ influences may stem from the past, its founders cite one specific idea by riot grrrl pioneer Kathleen Hanna to describe their approach towards the future: “Don’t revive it, make something better.” After all, the next wave of zine culture needs to re-evaluate to evolve—which, in this case, means ripping up and re-writing the riot grrrl format.

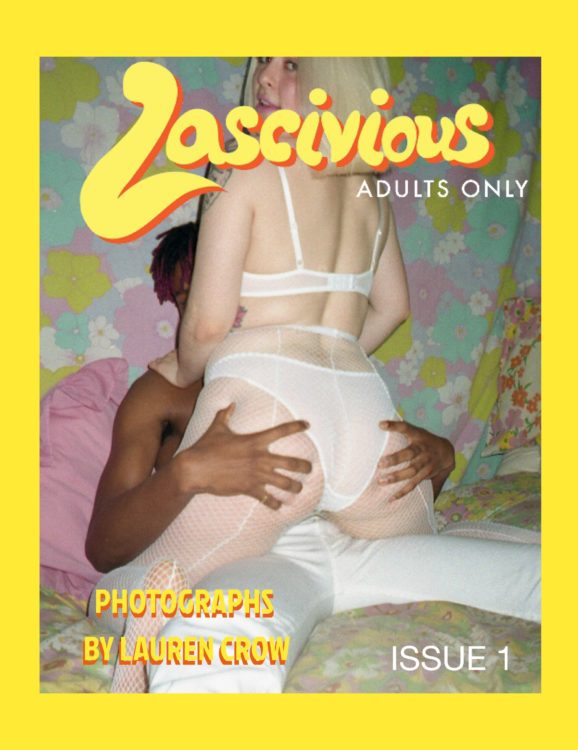

LASCIVIOUS

Divergent publishing may be on the rise, but decades of homogenised images and engrained taboo means some content is still not permitted to participate. Porn, unfortunately, remains largely in this category, and this is where NSFW, DIY porn mag Lascivious comes in. Curated and photographed by Los-Angeles based artist Lauren Crow, Lascivious is an “exploration of the sensuality and sexuality of my generation, questioning beauty ideals and who/what we consider beautiful”, Crow explains. Featuring vitally inclusive casting and an aesthetic plucked from a ’70s porn set—faded floral fabrics and a soft, analogue grain are abounding—the zine takes porn to an intriguingly intimate and vulnerable realm. Although that’s not to say the steamy, skin on skin scenes Lascivious lays on us are timid:

“My work could definitely be considered very shocking or uncomfortable to many people. Sex is a normal natural act, but we are only shown sex in very specific ways and with very specific people. There is still so much shame and disgust over sex and people who openly embrace and display these parts of their lives. But porn can be artful and beautiful—Lascivious was made to question what we consider ‘art’.”

Crow’s radical brand of page 3 empowerment is more than a subversive blip in the porn industry. With magazines like Lascivious on the rack, we are edging closer to a reality in which salacious sexuality is seen—and subsumed—by the art world.

FEM

Since its wholly DIY conception, the main object of London-based zine FEM has been to “diversify media.” For editors Georgia Mitchell and Mia Maxwell, this means creating content that “challenges the normative exclusion in media of marginalised genders, PoC, the queer community, and people with disabilities”. Intersectional, dyslexia-friendly, and utterly uncensored, FEM is a radical rarity in publishing—and a poetically personal one at that. This distinct tone all boils down to a submission-focused mantra: “the only way to produce a truly inclusive document is to relinquish editorial control and centre it on the voices of anyone who has something to say.” This resolute focus on empowering the individual also carries over into FEM‘s events—most recently, and fittingly, a radical zine panel, which offered seats at the table for marginalised voices—literally. For FEM, it’s through a combination of these IRL discussions and internet accessibility that publishing will progress:

“Zines are a way to break away from Instagram and screen culture and have something physical, uncensored and anti-mainstream but it’s also important to us that the content in the zine be accessed by rural areas, other countries, people without spare cash, etc. So for our latest Sex, Desire and Relationships issue—collating work from over 30 artists—FEM Zine has moved online, to make the work free and accessible for more people.”

FEM‘s online methodology may not be the traditional zine-making way—but perhaps it’s because its aims go beyond the traditional too. Mitchell and Maxwell hope their “push on representation will eventually bubble up to shape the norm of what is expected in publishing.” FEM is making sure marginalised perspectives are invited into the future of mainstream and DIY publishing—even if they have to break the door down.

Header image courtesy of FEM magazine