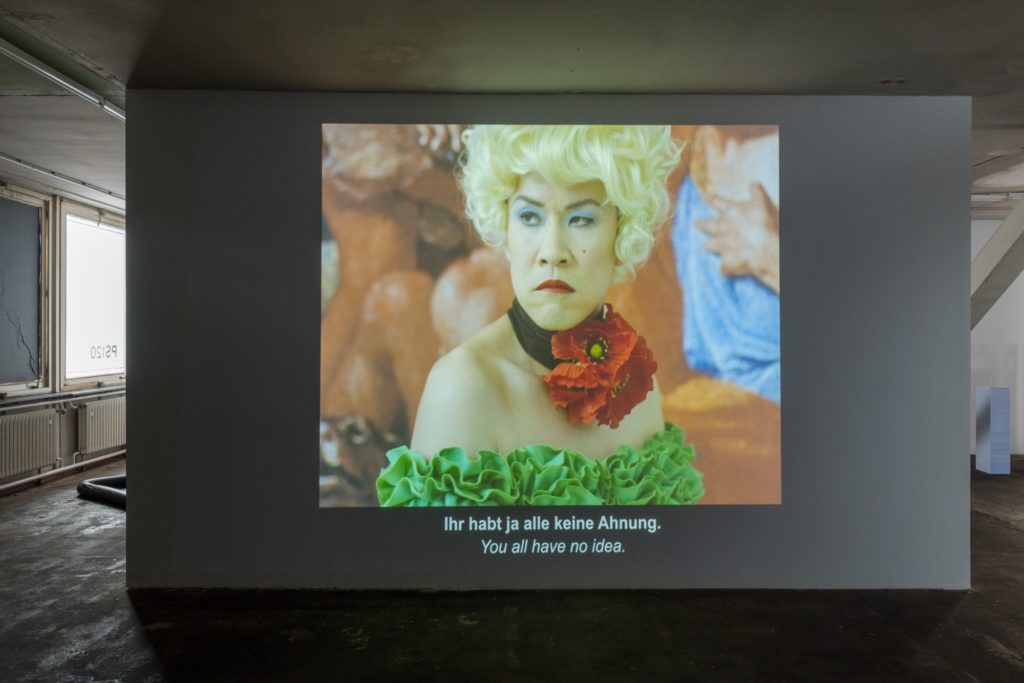

This summer’s pride brings with it two colossal red X’s in the queer calendar. June 28th marks 50 years to the day since the Stonewall riots first broke out in New York—perhaps the singular most important instance in the crusade for queer liberation in history. A month later it will be 100 years since the Institut für Sexualwissenschaft first opened its doors in Berlin. The birth of the Institute of Sexual Research is a lesser discussed cultural juncture, but it shouldn’t be. It was, in many respects, the genesis of gender reassignment surgery and queer research as we know it today. Now, a new exhibition at Berlin’s PS120, coined In-visible Realness, is fighting to ensure these foundations of LGBTQ+ life are never forgotten. The exhibition raises a number of questions: How do we quantify the shockwaves these events sent through time? In what ways does contemporary queer activism still correlate to these events? And what is it we need to remember in the first place?

Just after WW1, when the rest of the world was ignoring gay existence altogether, let alone the struggles of transgender people, Germany was an unlikely hotbed of underground queer spaces. At its vibrant core was the founder of the Institute of Sexual Research, Dr. Magnus Hirschfeld. Through the institute he formed the first official gay rights organisation to abolish homophobic German laws, pioneered gender studies, performed some of the first successful gender reassignment surgeries, and, to top it all off, wrote queer travel guides mapping Berlin’s gay bars and drag balls—all 100 years ago. If that’s not a pioneer, we honestly don’t know what is. The Institute of Sexual Research was violently yanked from the world by the Nazis in 1933. But in the wake of the burnt research lay the first flickering embers of LGBTQ+ emancipation—rekindled in full in the early hours of the morning in June in 1969 in a gay bar in Greenwich. The story is well known, a routine police raid blew into a flow blown riot spearheaded by a black drag queen, who threw the first brick. The queer community fought for days, but they were responding to the decades of systematic injustice and abuse they had suffered at the hand of institutions such as the police. This event led to Pride as we know it today—but more often than not, much of this history becomes lost to the joyful spectacle of the parade, which is why curators Justin Polera and Ben Livne Weitzman, alongside a host of Berlin artists, are revisiting and commemorating these catalytic events. Through performances, talks, photography, and installation, they the aim to widen the “heteronormative manner” in which we are taught history. To get to grips with In-visible Realness, and the complexities of queer history, we sat down with event curator Justin Polera and discussed where queer culture has come from, where it’s going, and “realness” à la Paris is Burning.

In-visible Realness explores the “shockwaves” Stonewall and the Institut für Sexualwissenschaft generated throughout history. What do you mean by shockwaves? And what else does the exhibition attempt to tackle?

This exhibition seems to do the impossible task of looking at this present moment in queer history, whilst simultaneously looking back at two locations geographically and two times historically, all at once. We agree with the theorists who say that in the face of an incredible need for survival a person is able to split themselves in two, defying the laws of physics, to be here and there at exactly the same moment. This is said of the enslaved person running for freedom. The shockwaves we refer to are the undercurrents (sometimes even unknown) that are still below contemporary queer activists that began 100 years ago. It is not a coincidence that in the told heteronormative Western white male history these are also critical years. In 1919 in Berlin, the Weimar Republic along with an unprecedented moment of sexual freedom before World War II. In New York City in 1969, protests to the Vietnam War collided full on with sexual liberation and the hippie movements.

Why do you think it’s important for these histories to be revisited?

History is not a single narrative. We shouldn’t only focus on what we’re repeatedly taught in school and in history books in a heteronormative manner. These two cases in 1919 and 1969—the establishment of the Institut für Sexualwissenschaft and the Stonewall Uprising respectively—are just as important and deserving of attention.

It’s also easy to take things for granted, which is why it’s essential to remember these, too often forgotten, queer histories and to be reminded of their significance. We must retell the stories and struggles for visibility of queer people and their right to be present everywhere, including in the public sphere: “You can be queer as long as you don’t show it in the streets.” This fight has always been a difficult matter, and that’s why revisiting the histories surrounding it is of such importance, to keep it alive and make it visible in people’s minds.

Where does the title In-visible Realness come from?

The title was inspired by the reference “undetectable realness”, which is a quote by Dorian Corey from the groundbreaking documentary Paris is Burning. I see the art of “realness” as the primary mode of queer artistic practices now, to which my co-curator Ben Livne Weitzman bought forward the word “visible”, due to the importance of the visibility in LGBTQ+ liberation. The hyphen in the title points directly to the process of making the unseen become seen (which relates to ideas around coming out). But it also brings together these two things that coexist, namely visibility and invisibility—both are needed to create site and non-sites of safety for the queer community.

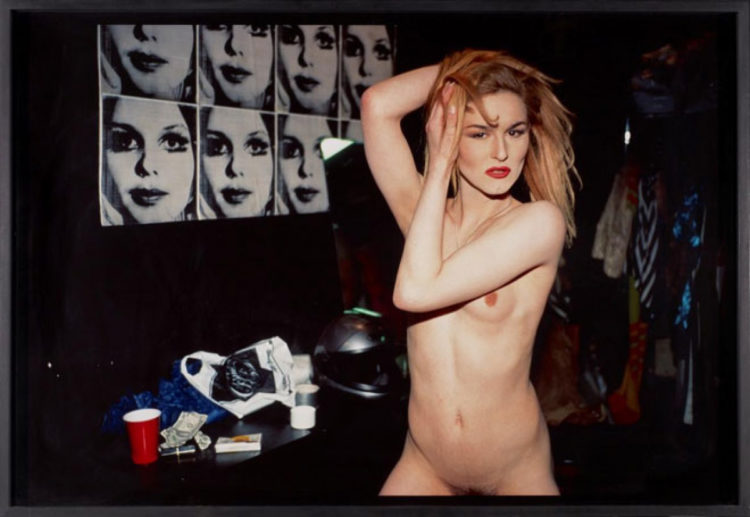

You have a wide range of artists involved in the exhibition, what are some of the modes and manners in which people are choosing to explore this history?

This exhibition presents archives next to contemporary art in order to compare them and make connections, bring forth what has been forgotten, and focus on their differences without separating them. The embodiment of queer figuration through abstraction is portrayed in various forms of media like paintings, photographs, videos, sculptures, and installations. The works are not explicit, and thus not defined within a certain frame, which allows for a bigger possibility for interpretation There is no depiction of people or action, they lack the presence of bodies, but they all tell stories united by their notions of pluralism and identity.

If we take a closer look into the exhibition, we can observe how an abstract painting by a queer artist, which would normally not be immediately described as queer art, within the frames of the other works, is attributed with a beautifully perverted note: “I desire to enter” embroidered into the canvas.

Event photography: Stefan Korte