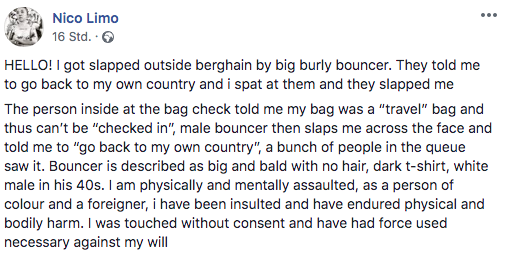

Some weeks ago, partygoer and organiser Nico Limo became the talk of Berlin’s freshman clubbing class after taking to social media to share an experience of brazen racism at the hands of a Berghain bouncer. The incident is the latest flashpoint in the Berlin club community’s biggest existential debates: how to stay true to its legendarily inclusive ethos as the city and its inhabitants change.

Per square-meter, few places in the world generate more conversation, or as wide a range of emotions, as the door to Berghain—the throbbing heart of the techno world. Getting in is a badge of almost unparalleled cultural clout, and being rejected is—there’s no other way to put it—humiliating. Tensions at the door run high, and the bouncers have a lot of power, which creates the possibility for confusion and all the ugly explanations that go along with it. Needless to say, we don’t condone spitting, and there are, of course, two sides to every story, but when somebody in a position of power makes you feel rejected or ostracised because of who you are, that’s a problem.

One of the many cults of personality to have developed around Berlin is its position as a haven for freaks and misfits; anyone who falls outside of a particular social boundary can find a place here, and what’s more, find a community—a family who accept them for who they are. Probably nowhere is that more true than in the city’s club community, which for the past pick-your-number-of-decades has held the world heavyweight title not just for quality of clubbing, but for its affordability and rigorously laissez-faire approach to inclusivity and expression on the dancefloor. It’s these second two that make the scene truly unique—it seems to hold some magical balance of a place where anyone can come to be whatever they want, and afford to.

But despite its utopian status for hedonism in its most free and inclusive form, the Berlin club scene is not without its issues. There’s always a story like Limo’s buzzing among the club community—that friend of a friend tale that passes through the city like a text from techno Gossip Girl. And it’s not just individuals either—from Konig Galerie’s ill-thought out Asian-themed party with Dandy Diary last year, which led to heavy backlash, to the controversial opening of the Humboldt Forum, fetishisation, tokenism, racism and discrimination are alive and un-well in Berlin.

The most overt place where inclusivity is managed is the doors of the club. Door policies are about plenty of things, most importantly keeping the party inside tantalising and relatively safe. It’s somewhat of a catch 22: in order to be safe and inclusive inside, certain people have to be excluded. “Door policies are one of the key factors that enhance and protect Berlin’s best clubs,” explains Sisyphos resident Fidelity Kastrow. “Otherwise they’d be over-run by wanna-be hipster types crowding out regulars. Door policies are also very effective at moderating people’s behaviour inside the clubs—queuing for hours and risking rejection seems to also make virtually every potential sex pest behave IF they get in (and that is a big IF).”

When Sven—the Berghain doorman who is almost as famous as the club itself—gets asked about how the bouncers decide who gets in, his answer is that “it’s subjective”, each bouncer makes their own decisions about who looks like they should or shouldn’t get in. That’s a good answer, and it’s probably true, but subjectivity (rather than, say, “safety”) is also a convenient format for people to mask or project other, more problematic forms of subjectivity—racism, ableism, homophobia, transphobia.

In a scene which relies on subjectivity as a standard, it’s easy for prejudice to be masked under the guise of exclusivity, but Willis Anne, founder of the record label and club night LAN, has always had positive experiences of the so-called crowd control implemented by bouncers. “I’ll always remember when I came to Berlin six years ago,” he explains, “my first impression and good feeling towards the Berghain club’s job at the doors. Straight and homosexual men and women, local and foreign people, of all skin colors, styles, young and old, casual to crazy. I liked seeing all this diversity inside the walls.”

But not everyone feels that way, and even just the possibility of discriminatory behavior can be enough to make people exclude themselves. “As a black trans woman, I often have issues with transphobic homophobic classist or racist bouncers who wish to flex on me,” says NYC-based DJ Jasmine Infiniti. “In Berlin, I remember attempting to go to Berghain with my daughter Yha Yha and rather than even bother I opted to simply forego it. I didn’t want to deal with the defeat and embarrassment of not getting in.”

Many of the clubs now considered pillars of the Berlin community began as places for gay men to meet (and fuck) at a time when homosexuality, not to mention queerness in general, was far more taboo than it is today. And while the scene still serves its original clients well, the queer community is broader and complex now than before.

Charles Schulz, of the iconic queer nightclub Schwuz, said that the one of the most important changes the club has made recently was welcoming asylum seekers and refugees. “The queer communities all around the world see Berlin as a place where they can be whatever they want to be. A lot of men—a lot of white, rich men—see Berlin as a place where they can have good sex and take a lot of drugs. If that’s your thing, that’s fine with me, but if you’re a Syrian kid who has little money but questions his own gender identity or sexual orientation, our door is definitely open to exactly you.”

Although Berlin has a well-earned reputation for being a multicultural city, and more than 1/6th of its residents are foreign-born, this doesn’t necessarily mean that it’s racially diverse, or that that diversity is integrated. Only 2% of the population is Afro-German or Black African, and only 3% is Asian, so the city still lags behind the racial diversity seen in metropoles like New York and London. In the absence of regular opportunities for people to get to meet and know people from other backgrounds, it can be easy for groups to self-segregate and remain isolated from (and misunderstanding of) one another.

This is exactly why freedom and openness of Berlin’s clubs have so much potential for inculcating integration. But inclusivity isn’t just about who gets in—it’s also about who lets people inside, who owns the clubs, who plays in them. Willis Anne says that increasing the diversity on the other side of the decks is one of the reasons he started LAN. “The audience is quite diverse, but I can’t say the same for the artists and lineups. I would like to see Berlin clubs invite more artists from South America, Asia and Africa. Also, even though an effort is definitely occurring to make space for women behind the DJ boot, I would like to see more female and queer artists play live.”

What the club cognoscenti do seem concerned about—and what probably almost everyone in Berlin apart from a handful of investor-types is worried about too—is how the increasing amounts of money pouring into the city will affect who can live here and thus who forms the basis of the party scene. Femme Fraktale’s Madalba is worried about the direction that Berlin’s club scene is taking. “Just look at the increase in entry prices in recent years, in most cases almost doubled. There is a process of commercialisation happening, closely linked to that of gentrification, which is endangering that same diversity that has always characterised the Berlin club public.”

Instances like Limo’s are inexcusable, and completely avoidable, but the sad truth is that they do happen. Race, sexuality and the many other dimensions of identity are complex, and every negotiation offers chances for people to screw things up. These issues will likely never disappear completely, but they can (and must) be combatted through speaking out, acting in solidarity, and refusing to tolerate discrimination in any form. For every one instance of hate or prejudice, there are thousands of Berliners who will not stand for it, and that’s the spirit keeping club culture alive here. Money, on the other hand, has a pretty clear track-record of marginalising everyone without it, and the violence that it causes is often more diffuse. Berlin doesn’t need to worry about good dance music shoring up any time soon, and there’s as much goodwill towards outsiders here as you’ll find almost anywhere in the world. But all that good stuff means that more and more people are clamouring to buy a piece of it—and that’s something we should worry about letting into clubs.