Although he’s the founder of his own eponymous label, to call Wekaforé Jibril a designer is to do him a disservice. Frontman of sultry electronic ensemble Egosex, architect behind afro-funk afterhours Voodoo Club and now producer of an afrofuturist sci-fi series, the Lagos-born, Barcelona-based talent is living proof that you can be a master of four trades, jack of none. Unified by a resolute vision and uncompromising politics, his multifarious output is an unabashed celebration of Africanness that reframes colonialist rhetoric and sparks infectious energy in the process.

Jibril’s newly launched ‘Spirit 002’ collection approaches the dichotic concept of primitivity that arises from the ‘othering’ of Africans by their European colonisers. The result is something the designer terms “primitive futurism”, the process of legitimising primitivity by imagining a future in which the capitalist mindset—that governs the Western world and equates cold and distant technology with progress—is overthrown. The notion of primitive futurism may seem oxymoronic in a culture driven by consumerism, but for Jibril, it’s a not-so-distant dream. “I don’t think it’s that much of a paradox,” he argues. “Society has made us think that they’re so different, so opposite, but I think we could comfortably move into a primitive future.”

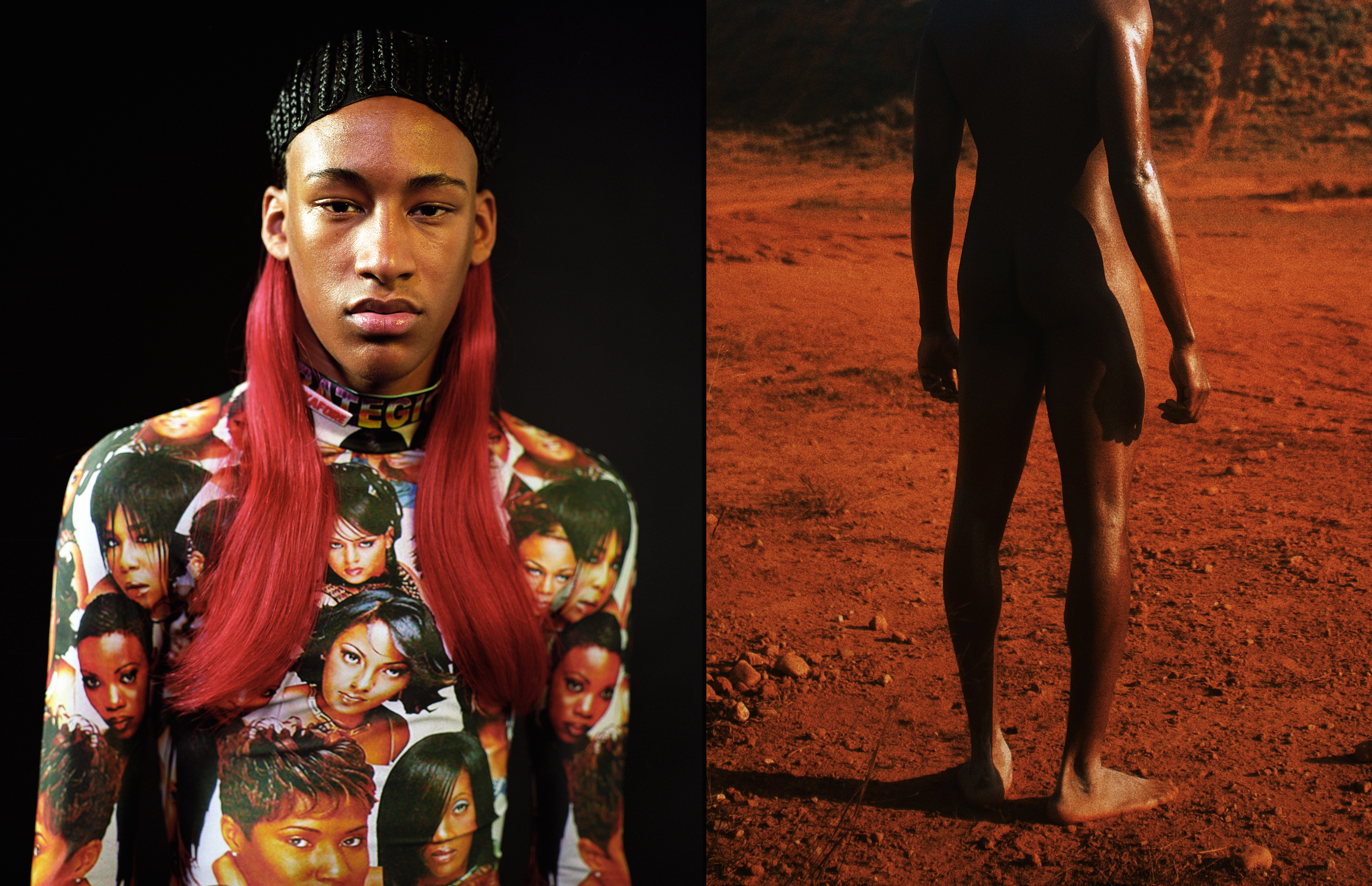

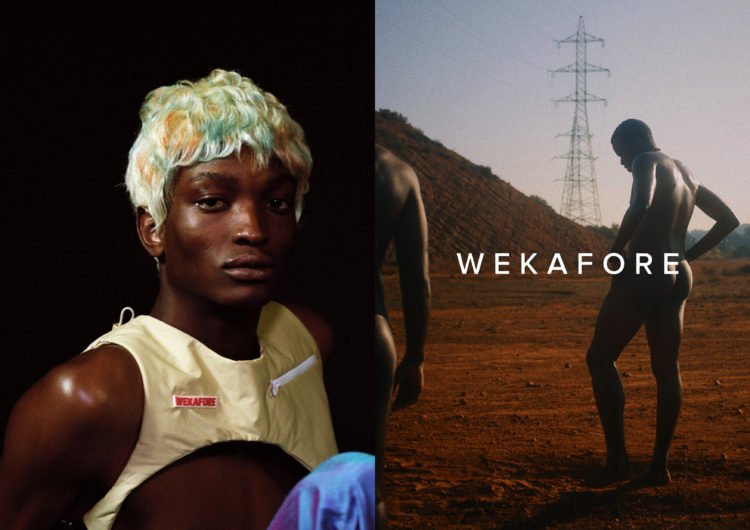

It’s this premise that guides Wekafore’s subversive designs, from icon-rich long-sleeves to the collection’s piste-de-resistance: a flesh-revealing leather chest rig that occupies the ambiguous realm between clothing and nakedness, re-affirming that the actions of wearing and covering are not inherently synonymous. “This is my take on primitivity,” Jibril elaborates. “When I imagine the collection, I almost imagine it without clothes. I imagine nakedness and purity. This piece is about necessity—a piece of wearable leather that holds your wallet, your keys, your phone.”

Drawing on the jarring duality of the European vs African perspective, Jibril’s colourful designs are loaded with symbolism, somehow marrying the stark polarity that plays out between the coloniser and the colonised. “When I started the process of developing these thoughts, I researched the European perception of primitivity—the first Europeans who took anthropology trips to Africa to take pictures of these ‘savages’ and how they portrayed us, how they talked about our culture; how they brought it back to Europe and sold it and used it for some National Geographic shit.”

Through Wekafore, Jibril takes the negative connotations of primitivity—the preconception that Africans are lesser, animalistic beings—and propels them into a new realm, one that defies the patronisation of colonial primitivism that’s still being unlearned today. “I wanted to rethink that, and turn it on its head by making primitivity cool.” By ascribing status to the Western-invented primitivism so heavy handedly thrust upon the entirety of Africa, Jibril takes ownership of primitive identity, reframing it within the context of provocative fashion. “Europeans saw us as primitive,” says Jibril, “but we saw ourselves as being one with the land, one with nature, only using what is necessary, just living. This is before technology came, before they gave us guns, you know. It’s sort of like an inexplicable amalgamation of both sides: how do I take both sides and make them into one thing, and make them survive each other?”

As their titles suggest, Wekafore’s ‘Spirit’ collections are also inspired by a notion of spirituality. For Jibril, what that entails is inherently shaped by his strict Christian upbringing, and the disillusionment it brought about later in life. “It’s still very much a part of me,” he admits, “the way I talk, the way I see myself, the way I see the world. But as you grow up you get more information about where you’re from, your history, where Christianity is from, what Christians have done, what they did to bring that religion to Africa.” Disenchanted with, or perhaps more rightly enlightened by the complex nuances and problematic history of a religion chosen for him in childhood, Jibril shaped his own spiritual outlook in adulthood. “I sort of morphed my own beliefs. I have more accommodation for other belief systems, even now that I know that these belief systems are indigenous to who I am, to my skin.” From name to nuance, ‘the spirit’ runs through Wekafore’s inimitable ouevre, which features t-shirts and hoodies stamped and branded and with the phrase. Although ‘the spirit’ is, to Jibril, an indescribable essence resisting categoric definition, its embodiment can be felt, and thus communicated, through his creations. “I can’t explain the spirit,” he stresses. “You either have it or you don’t. It’s just in the air and I can feel it and you can feel it, we all can feel it, but we deny it. We’ve grown up denying the spirit, but the spirit is real.”

The Wekafore aesthetic is also rich in iconography, adopting black bodies, faces, silhouettes and characters as its patterns, which Jibril describes an unconscious and instinctive pull towards. “I guess subconsciously I just wanted to normalise blackness as a high form of art, just the same way as we have these greek statues,” he explains. “How they romanticise the white body as godly, that’s the same thing I want to do for black bodies.” An unabashed form of self-celebration, Jibril calls this revolution “romanticism of the primitive negro”—”it makes me feel like I’m romanticising myself.”