Among increasingly right-leaning rhetoric, racism, and religious division, former child soldier Emmanuel Jal spreads the spirit of activism and hope.

Imagine being eight years old and operating an AK-47 bigger than you are. Emmanuel Jal doesn’t have to imagine. Recruited as a child soldier by Sudan’s rebel army sometime in the late ‘80s—he doesn’t know exactly when—Jal was made to fight in the same war that ravaged his country and killed most of his family. Lasting 22 years, the Second Sudanese Civil War is one of the longest civil conflicts in history, with one of the highest number of fatalities since WWII. The Sudan People’s Liberation Army (SPLA) mainly represented Christians and animists, and fought to overthrow the country’s central Muslim government and re-establish the autonomy of South Sudan.

Jal witnessed his aunt’s rape when he was just five. At seven, he and many other children were kidnapped and taken to SPLA training camps in Ethiopia, which were disguised as schools so as not to rouse suspicion from the UN. At his most desperate, profound starvation led him to contemplate eating the rotting corpse of a fellow child soldier. When other kids were merely playing with Action Man figures, Jal was living it.

If hatred starts as a seed, it was planted in Jal early on. With every negative experience he endured at the hands of “the Arabs” or “the Muslims”—who quickly became synonymous with ‘the enemy’—the feeling of hatred grew. It wasn’t until he was 13, after his escape and subsequent rescue—by British aid worker Emma McCune, who took him to Kenya—that he came to realise the war was never really about religion, but about resources and power: Money, diamonds, and oil. “I learned that those Muslims who came to burn my village had also been indoctrinated,” he explains. “The government were using them for their agenda, and religion was an excuse to justify their actions, to avoid guilt.”

Since escaping to Kenya, Jal has forged himself a new, peaceful path in life, namely through his internationally acclaimed music—which has seen him play to a crowd of almost 50,000 at Nelson Mandela’s 90th birthday—and peace activism, for which he was awarded the Dresden Peace Prize in 2014. He’s has acted as a spokesperson for the Control Arms and the Make Poverty History campaigns and strives to put a stop to enslaving children in war. The 2008 documentary War Child, centred on Jal’s life, won the Cadillac Audience Award at the Tribeca Film Festival and was followed by an autobiography of the same name.

Founding Gua Africa—a charity focussed on education in Africa—performing internationally, and fronting global peace efforts with WWP (We Want Peace), Jal is on a journey to reframe his trauma and incite change. And in an increasingly right-leaning society peddling racism, police brutality, rampant Islamophobia, ‘othering,’ and mass panic, the message he spreads is one that needs to be heard.

*This interview was conducted in January 2020, and is taken from INDIE’s SS20 issue.

At the beginning of your autobiography, you speak about your father’s army career—his joining the SPLA—and the level of pride you felt being associated with that. Did you want to follow in his footsteps?

My father dressed me up in that uniform, and as a child, I had no idea what that really represented. I knew that people who wore it were strong, and people were afraid of them—that was what I wanted. As a kid, you want to be like your parents—they’re heaven for you; they’re everything.

Your mother was a strong Christian. What role did religion play in your childhood?

When I was young, religion helped me; it kept hope alive. My mother used to pray—when things were difficult, she’d go to church and sing, and her tears would become tears of joy. Knowing that there is a creator above, someone who looks over you, cancels your worries; it makes you believe you’re here for a purpose.

In your book, you also very pertinently describe the hatred between different religious people in Sudan. Do you feel like you were indoctrinated?

The day an Arab raised his hand to my mother was the day that set me on a path to hatred. Later I was separated from my mother, my brothers, and my sisters. What we knew—the life, the beautiful life we had—was taken. By the time I was trained to become a child soldier, there was no indoctrination being done—I wanted revenge for my family.

How did your perception of the conflict change?

It took me a long time, but eventually I understood that religion was being used to blind the public and to mobilise more forces to support the government. They wanted diamonds, gold, the land, the manpower, and the oil. Free labour—that’s all they were looking for. Our cows—that’s what they’re looking for. It wasn’t because God hated us, but they used religion to justify their actions, to avoid guilt.

When did you first have this realisation?

That knowledge only came when I was in school in Kenya, when I was able to learn. At that moment, I knew I had to widen my perspective; otherwise, I would have thought all Muslims just hated us for real. By understanding that, I was able to let go and choose a new path.

That ‘new path’ is one that’s now very much rooted in hope. Not only do your lyrics spread this message, but you founded the Gua Africa charity, you’ve campaigned against arms, and give life coaching around the world. Why is activism so important to you?

It was part of my transformation. I felt like I had an opportunity to enlighten, and I always wanted to be part of a solution. The new understanding I got gave me a new insight—that I could pursue a different path that didn’t spread hate. If you look at the different types of activism, much of it is driven by anger, and I get it, I was there. The activism I’m doing now is about turning inwards and also bringing peace in myself.

The more peace I have within me, the more I can give it out. You can only give what you have. If you have hate, you’re gonna give hate. If you have fear, you’re gonna give fear. If you don’t respect yourself, if you don’t respect your thoughts, if you don’t respect your worth, you’re not gonna respect other people’s thoughts, other people’s opinions, other people’s values. Before, my activism was more aggressive, more forceful, but now I’m saying, how can I focus on myself and then make more of an impact? Hit people with compassion.

Do you believe in evil?

I believe goodness is inherent in all human beings. Every person we portray as evil is just being controlled by their fears; they have their own traumas; they feel threatened. I look at any person who is spreading hate and I see that they need compassion. They have their own anxieties and worries, and that’s what leads them to that which we describe as evil. Sometimes I look at it on a very basic level—you can go into someone’s house, and brothers and sisters are fighting over simple things. If that can happen at home, how is it outside? People use ideology to justify the evil they’re doing—either they use religion or they use ‘othering,’ by making a group of people out as ‘subhuman,’ just as they did with Jewish people. When Africa was colonised, people saw us as lesser beings. But the people who spread this hate are victims themselves. They’re victims of their own fears.

The things you witnessed in your childhood are some of the most abhorrent acts of human nature. How have you managed to process that trauma?

I never understood what trauma was. When I was still in that survival situation, it wasn’t there. But when I went to Kenya, and I was finally in a peaceful environment, I started having flashbacks and nightmares. Trauma is like a mental genocide, a murder of your soul, an invasion of demons occupying a space in your mind, where you have flashbacks in the day and then nightmares at night.

And how did you overcome that?

Trauma takes away your confidence; it takes away your courage; it takes away everything. You live in your head—you’re living in the past, and that makes it hard to move forward. It’s like a virus has entered your brain to freeze things, so you don’t function like a normal person. I had to relearn things; it wasn’t an easy thing for me. As a kid, before the war, I was very lucky; I had lightness in my heart, and joy. I always knew how to lift myself up, get outside, go and play, or crack jokes, or listen to stories. And so, what I came to understand is that to overcome your trauma, you must have a dream; you must know your purpose and then change your environment. I had to create this lifestyle, to meditate and to reprogram myself. Now I teach these things to other people.

This interview comes at a very pertinent time—a WWIII, in some senses, seems plausible. How does this make you feel?

If you look at most kingdoms that became strong, they grow as they take other kingdoms, or take other people’s resources. There’s this fear of resources—like, if China becomes powerful, the US may lose power; and if Russia becomes powerful, then China may lose power. A third world war is possible, but I’m not going to live in fear—I live my life everyday beautifully.

But I also have a responsibility to think about how I make this world a better place, and that’s what matters. Who are you voting for in the system? What values do you want to see in the leaders you’re voting for?

How do you think we can overcome hatred?

If you go into the wild, a lion will only attack you if they’re hungry, or they feel threatened. A lion will not just attack you for no reason. Human beings are the same: They attack because of fear. The Nazis were fearful of the Jewish people; they saw their resources running out. If you look at racism, war, whatever it is, it’s fear. How I see it is that, to overcome hatred, we need to widen our perspective. We need to educate people; we need to be willing to learn.

Forgiveness is also one of the most pertinent lessons in religion. How would you describe your relationship to religion now?

I’m more open to it. I read a lot of religious books, and I realise that they’re all talking about the same thing—they’re talking about love. Religion offers people an opportunity to fill the empty void within them. When people are vulnerable, they can be hypnotised by it—by whoever they put their trust in—and so, staying open is the best way to move forward.

I’m wary of wolves in sheep’s clothing— hypocritical people who hide themselves behind religion and use it as an excuse. I judge a person by the actions they take. If you say peace is in you and if you say love is in you, then let me see it.

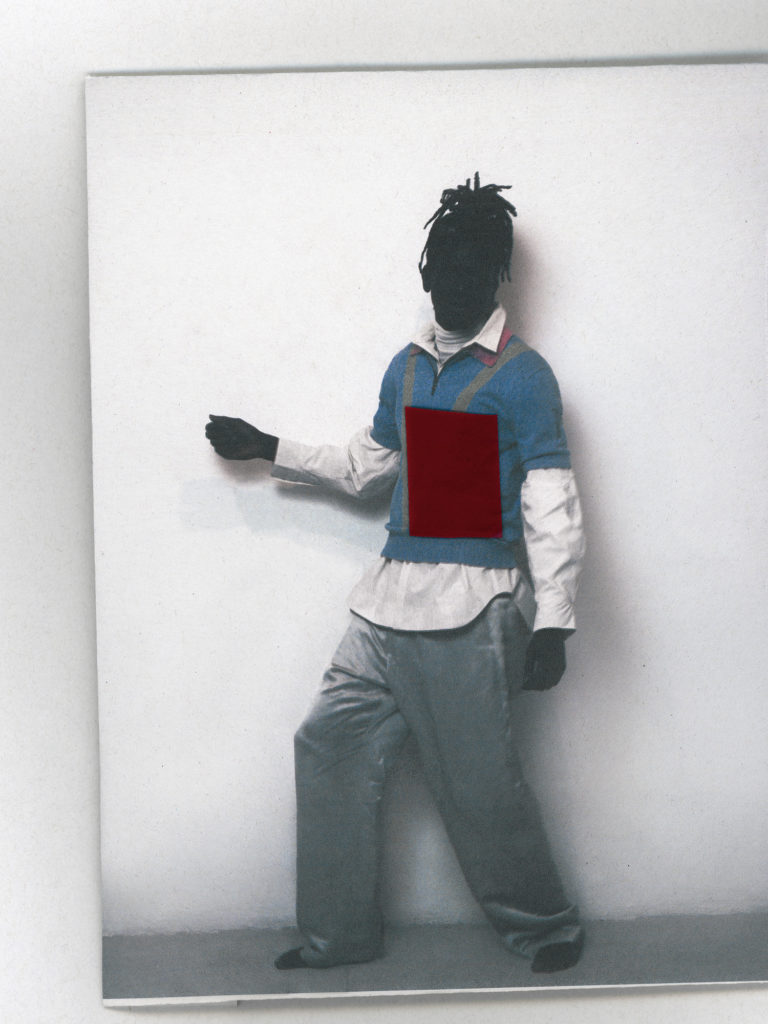

Photography LETIZIA GUEL

Styling SERENA POMPEI

Photography Assistant AGNES VIRAG

Styling Assistant ELIZABETH KWAN