Few words are as closely tied to the SORRENTI dynasty as the phrase ‘heroin chic’. But twenty years after the rise and fall of New York City grunge and the Kate-Moss-fuelled drug-addict aesthetic that swept the ‘90s, Francesca Sorrenti is still fighting to clear her family’s name.

When Juliet asked, “What’s in a name?” she hadn’t met the Sorrenti family. They may not hold the same power as the Medici, or the insufferable prolificacy of the Kardashians, but the Sorrenti name stands for something, and that something—ever a rarity in this day and age—is talent. A creative dynasty spanning every alcove of the artistic industry, the Sorrenti family begins with Francesca, continues with Mario, Vanina, and Davide, and ends—at least for the time being—with Gray and Arsun. Which of those names sticks out to you most will likely depend on your age and inclination, but be it Mario’s era-defining nude photography peppering the pages of Vogue, or his inextricable ties to Kate Moss; Davide’s youthful portrait of NYC subculture; Vanina’s visionary work as a photographer and stylist; Francesca’s contribution to fashion photography; Arsun’s new-age rock music; or Gray’s punk-edged portrayals of Miley Cyrus, utter the name ‘Sorrenti’ among creative circles, and you’re bound to make conversation.

But lately, owing to the documentary See Know Evil that sheds new light on his life, one name has dominated the Sorrenti sphere: Davide. “It’s pronounced David, but it’s got a silent ‘e’ at the end,” his mother Francesca gently reminds me in her soft New York accent over the phone. “People often get that wrong.” But his name isn’t the worst thing the world has got wrong about Davide. The late photographer, who passed away in 1997 at the young age of 20, was swept up in the heroin epidemic that plagued the fashion industry in the ‘90s—without ever being an addict himself. Thanks to the media, Davide became the poster child for ‘heroin chic’—the now-notorious phrase coined by Ingrid Sischy in relation to the way the industry glamorised the drug—and his death was wrongfully attributed to an overdose. “When Davide passed away, it was a media frenzy,” Francesca remembers. And she’s now blazing a trail to rewrite his story and right the wrongs of the global press through her close collaboration with the film’s director Charlie Curran. “His death ended heroin chic,”she explains. “But somehow they started blaming him for it. He was 20—that wasn’t fair.”

“Davide’s death ended heroin chic—but somehow they started blaming him for it.”

To the world, Davide was known as a rebel, caught up in skating, drugs, theft, and graffiti. He embodied the same youthful ‘DGAF’ spirit that came to serve as an image for mid-‘90s New York thanks to artists like Larry Clark and Davide himself. New York magazine called his crew “prep-school gangsters”—a bunch of privately educated kids infatuated with the hip-hop mindset and trying to assimilate life in the streets. “It was during that period in New York where everyone wanted to be a gangster,” Francesca explains. “Everybody wanted to sell weed. He had a touch of juvenile delinquent in him—he shoplifted; he did things I could have killed him over.” But to his family and friends, Davide was unique and effortlessly endearing.

He was, after all, practically a child, and looked even younger—a symptom of the chronic illness Cooley’s Anemia (a rare blood disease) that would eventually lead to his death. “He was always getting everyone else into trouble, and always getting away with it because he looked so young,” Francesca laughs. “He could go to the movies and pass for the twelve-year-old rate until he was sixteen.” And Davide was a trendsetter—the brains behind streetwear label Danücht (and that infamous ‘MODELS SUCK’ T-shirt)—and known among his friends for his unceasing ability to think bigger—to do things first. “He was always the leader of the pack,” his mother assures. He’d cut his own hair, create his own DIY style, and people would follow. “You couldn’t put him in a box,” Francesca tells me. “He loved golf just the way he loved rap music. He used to sing opera in the shower he loved Pavarotti, he loved 2pac, Bob Dylan.”

It was because of Davide that, in 1982, Francesca—herself recently divorced—uprooted the family to New York from Italy, where Mario and Vanina had grown up, in order to have access to better healthcare. But New York wasn’t easy. In Naples, working for Fiorucci and eventually creating her own clothing company, Francesca was the eccentric, clog-wearing fashion hippy—“they called me Francesca La Pazzo,” she laughs. But in New York, she was the single mother of three, desperately trying to find a creative job that allowed her time off to take Davide to hospital appointments and for his biweekly blood transfusions. “It was difficult,” she admits. “Back then, no-one in the fashion industry had children. It was just unheard of to mix the two.” But, after landing a job in an ad agency and being introduced to styling, Francesca found herself holding down three jobs while looking after her three children. “When there’s a will, there’s a way,” she affirms. “I’m very big on proverbs right now.”

Growing up, the Sorrenti family were close, owing, in part, to Davide’s condition. “They were the three musketeers, ”Francesca remembers fondly. “They were always looking out for each other.” And creativity was a central part of their lives. “The house in Italy was always full of beads, pearls, and fabric,” she reminisces. “My ex-husband’s room was full of paint—he’s a painter. Mario was always drawing or playing; I thought he was going to be a fine artist. Nina was always reading fairytales—she loved Alice in Wonderland—but I knew she’d be a stylist at one point in her life, because she loved clothes.” With only a five-year age gap between Mario, the oldest of the children, and Davide, the youngest, the Sorrentis grew up in close proximity, looking to each other to learn and grow. Davide’s sense of style was, his mother guesses, influenced by his siblings’ start in the industry. “He was very young when Vanina started modelling,” she remembers. “Mario was a model, too. Once in elementary school, he put on a pair of pink socks because he thought they were cool.”

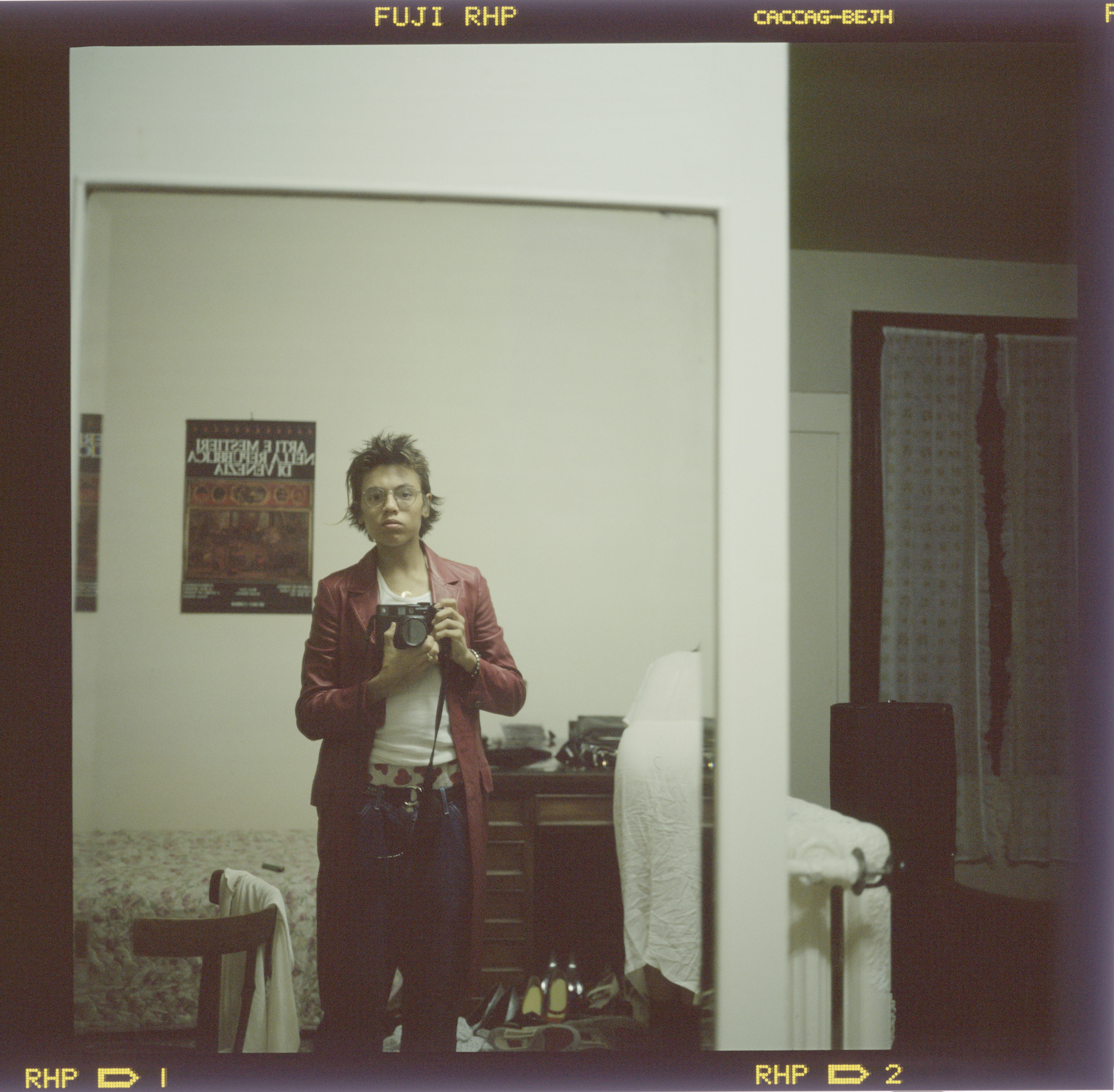

And it was Mario Sorrenti, too, who catalysed Francesca’s own photographic career. “At the time, he was a model, and he had just met Kate” (she’s on first name terms, obviously, but she’s referring to Mario’s then-girlfriend Kate Moss). “He came home from London one day and said, ‘mom, why don’t you pick up a camera—you’re always telling everyone else what to do’,”—and she did. Francesca quickly became revered, shooting for i-D, The Face, Dazed & Confused, Vogue, and frequently for Interview under Ingrid Sischy. “I was grateful that I became successful very quickly,” she tells me. “I guess it was because I knew everybody at that point. I had an ad agency, I had been a stylist, I had been a designer.”

But it was during her time as a photographer that Francesca became confronted with the drug-fuelled frame of mind that was beginning to wreak havoc on the fashion industry, and would end up tainting the Sorrenti name. As her career progressed, landing big shoots with even bigger magazines, the effects of heroin became impossible to ignore. “I was starting to freak out,” she remembers. “I was shooting, and the models were shooting up.”

“There was Kurt Cobain, there were drugs, there was grunge—everyone was a tortured soul.”

“I remember the first time I was out in LA; a young lady came in and I said, ‘what’s up with you?’,” she says. “She started to cry. I told her i couldn’t shoot her; I called up her agency and asked the girl for her mother’s number. Her mother put her straight into rehab.” That quickly became Francesca’s life, helping young girls and speaking up about the injustices she saw plaguing the industry. “You’d hear hard stories in the fashion industry—photographers lifting girls against the wall to take a picture. Photographers and assistants doing heroin with models—it was all very out of control.”

Drugs were becoming commonplace—not only in the fashion industry but across pop culture. From a young Leo DiCaprio in The Basketball Diaries to Chloë Sevigny’s dishevelled angelicness in Kids, the aesthetic of drug use and abuse was being pushed firmly to the fore. And it was a problem that, especially in the Sorrenti family, couldn’t be ignored. Kate Moss was the face of everything, and—lensed by Mario as part of Calvin Klein’s now-iconic 1993 campaign for Obsession—would later become the face of the heroin chic aesthetic. Actress Jaime King, then-girlfriend of a teenage Davide, was using heroin from as early as fourteen. “Young girls were doing drugs because they thought it made them cool,” Francesca tells me. “Photographers who never did drugs in their life all of a suddenly started, to be down with the models. Agencies were hiring kids to be bookers, and they were doing drugs. It was crazy. It was a really weird time.”

When I ask her why—why then, why so young—Francesca sighs. The thing is, nobody is truly to blame because I think it just happens. Just like in the ‘60s, it was a revolution. There was Kurt Cobain, there were drugs, there was grunge—everyone was a tortured soul, and the media started to give that credit. Without the media, there would be no ‘heroin chic’. If the media didn’t idolise Kurt Cobain and grunge—I’m not even talking about fashion—it all just tumbled.”

“Even the fashion people allowed certain things to happen in order to be ‘cutting edge’. They didn’t think anybody was going to die.”

It explains the misinterpretation of one of Davide’s most notorious images. The photograph shows Jaime King sitting on the sofa, cigarette in hand, reading a magazine. She’s wearing ripped tights and has dark hollows under her eyes, and she’s surrounded by posters of Nirvana and Kurt Cobain. “That was so misconstrued,” Francesca explains. “At that time, Davide did not do drugs; he was worried about the state of things. That was a story about the ‘eve of destruction’. Vanina had put up all of these posters, ripped the tights and made it look like it was a druggy den.” It was published only after his death, out of context, but that image became a symbol of Davide’s life—used as evidence of the life the media reported him to be living.

As far as his mother is concerned, it took Davide’s death for people to wake up. Though the cause of his death wasn’t the miniscule amount of heroin he took (he’d been on holiday in Mexico and missed one of his blood transfusions), for the three months it took to receive the toxicology report, everyone—including his mother—assumed the onslaught of ‘overdose’ headlines in the media were right. “I got really mad,” she admits. “I said to the kids, this isn’t cool, this isn’t chic—this is heroin. If you continue to do it, this is how you’re going to end up.

“The only good that came of his death was the end of heroin chic,” she tells me. “I got letters from kids who said they were going to stop doing drugs because of Davide. They felt they were creative, and they were hurting, and that drugs were not the way to go.” And now, over twenty years later, Davide’s story is being resurrected—this time by those who know it best—for a new generation. See Know Evil, which has already made waves on the international film festival circuit, and will be released on iTunes in September, interlaces never-before-seen images from Davide’s short, but influential archive with intimate interviews from his inner circle, painting a truthful portrait of his life that allows his legacy to live on, unchained from heroin chic. “Davide didn’t deserve the life he had,” his mother reaffirms, but if his story has the power to speak to people, and change the status quo, then we can be forever glad that he lived.

See Know Evil will be available to stream on iTunes from September.