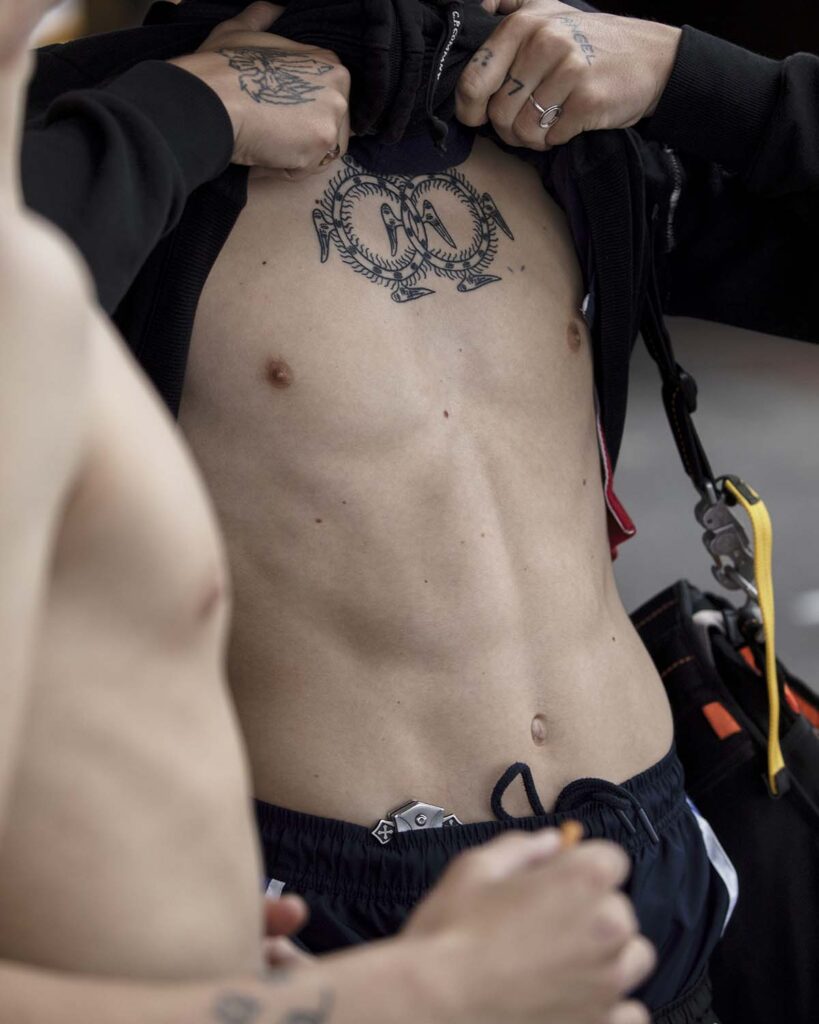

Monster and Primark may not scream high fashion, but photographer Winter Vandenbrink captures them with the same intensity as he does Louis Vuitton or Bottega Veneta. Growing up an only child in the Netherlands, his own shopping-mall-loitering teenage years have developed into an adulthood spent documenting the turbulence of urban youth. Now residing himself in the metropolis of Paris, Vandenbrink’s work chronicles inner-city anxieties against steely-grey backdrops, anchoring subcultural significance in backpacks, tattoos and tracksuits. Such concrete symbols exhibit a gritty masculinity, but the bravado and boisterousness are always tempered by the fragility and softness of youth. Vandenbrink captures his subjects off-guard and up-close, freezing transient moments of intimacy and vulnerability. Bored with the overly staged shoots which dominated his early career, he became interested in what he calls “camera-unawareness”, and subsequently developed a more voyeuristic approach to his art. The resultant images are an outsider’s observation on the construction of urban youth culture, an exploration of group mentality and belonging, and, in the photographer’s own words, an investigation into “the possibility (or impossibility) of creating an individual identity when everything now is so branded and ready-made.”

This series—Vandals—borrows its name from a 1945 text by German philosopher Theodor Adorno. Chosen by Winter’s boyfriend, it explores the challenges to individuality posed by increasing consumerism and mass-culture. Below, Vandenbrink reflects on his own experiences, the challenges faced by young people today, and his methods for catching it all on camera.

The photographs in Vandals are a voyeuristic glimpse into urban youth culture. Do you find that there are any challenges specific to capturing inner-city life?

Actually, there weren’t that many. I did have to think about whether the subjects of the photos should see me, though. In the beginning I shot undetected from very far away, but that started to feel a bit dishonest. So I moved in closer and closer. Now I like to stand in the middle of the action, or at least in a spot where the young people can see me and approach me if they want.

Your work shows masculine identities under construction—there’s a harshness to it, but with elements of femininity and androgyny too. Is that something you try to explore?

I don’t have an agenda or a selective approach like that. I simply like to cover the whole spectrum of adolescence and its transformational process, looking specifically for instances of friendship and togetherness.

How do brands—in this instance those like Monster, Primark or Supreme—galvanise your subjects and your work?

They’re hard to miss! I’m interested in the uniformity these logos create, and how the brands that people gravitate towards, as well as the meanings behind them, shift over time.

Where did your preoccupation with capturing the movements of the body come from?

This came with my desire to capture camera-unawareness. When the shoot isn’t staged, you start to see the more natural and intimate dynamics of the moving body. When you look at the work of Eadweard Muybridge, for example, you see that you can cut to the heart of something by viewing it in the moment, in motion.

Your photos are often close-up and specific. Are you a detail-oriented person?

I love details and close-ups because of the definition it brings to clothes and skin. Maybe this has something to do with my experiences growing up: I lived my adolescent years in a blur because I didn’t want to wear my prescription glasses, and I wasn’t allowed to wear contacts at the time. I could only see things in focus when I got up close.

You’ve said that filmmakers are often your biggest inspirations. Whose work do you most admire?

I love the magical realism of Apichatpong Weerasethakul. His work captures the mundanity of everyday life, but subtly brings in the spiritual world. I’ve also become infatuated with Fassbinder’s work, not for the beauty of his images but for the way he sets up stories and deals with social issues. I have a lot of love for the subjects in his films. Finally, I watched Close by Lukas Dhont recently, which tells a story similar to my own work. This one ripped my heart out because of how it’s told and visualised. It’s a devastating film, and it hit close to home.

Streetwear or runway? Or both? Your work blurs the boundaries…

I love both equally—and yes, I love to blur the boundaries!

Do you think young people today have a religion?

I wouldn’t describe what young people have as a ‘religion’—I think that comes later in life. But they certainly idolise certain brands and certain people. According to this old viral video about Monster, they’re all Satanists. Maybe there’s something in that—there is a constant need to subvert, after all.