The tragic killing of George Floyd by Derek Chauvin may have been one of the most brazen acts of racism in recent history, but as demonstrations move beyond US borders, one thing is becoming abundantly clear: Racism is not just an American issue.

Igniting passionate organisations of protest worldwide, cities from Berlin to Brisbane have taken to the streets—in times of a global pandemic—not only to showcase solidarity with their American brothers and sisters, but to question and address the physical, mental and emotional abuse faced by members of the black community in their hometowns.

“There is still a deep denial and ignorance around the role Britain has played in designing, birthing and exporting racism across the globe, particularly to the USA as a former colony,” says Siana Bangura, an activist from South East London working with Black Lives Matter UK. “Yet in the UK, and other parts of Europe, the language used to discuss racism works to frame it as a ‘foreign’ problem.”

If there was ever any doubt on how deeply rooted white supremacy is in European societies, may the rapid mobilisation and shocking showcase of far-right activists at Black Lives Matter rallies disprove your theories. Some call them “football hooligans”—others “statue protectors”, but the hundreds of angry (primarily white, middle-aged) men who turned up in London’s Parliament Square are nothing short of white supremacists—backed by right-wing organisations like Britain First.

The truth is, Europe is not only guilty of subjugating black and brown bodies to dehumanised conditions, but culpable for the creation and exportation of racism around the world through extensive and deep-rooted colonial structures. “I think an important distinction is also that Europeans—who invented constructs of race—facilitated the practice of white supremacy and slavery in foreign soil—in their colonies,” explains Mitchell Esajas, founder of Black Archives Amsterdam. “The USA in contrast has experienced the violence of slavery on American soil, and they have a much larger and longer history of resistance.”

Esajas points out that most black people, especially from former colonies, really began to migrate to Europe after WWII. “The post-war discourse around race changed drastically as Europe itself had fallen victim to racial ideology,” he explains. The aftermath was that nations like the Netherlands committed their societies to becoming liberal and open—discussing their colonial history as a fact of the past. “Obviously that sounds good in theory, but in practice racism continued to manifest itself in different ways. Although there was no Jim Crow here, it doesn’t mean there wasn’t institutional racism.”

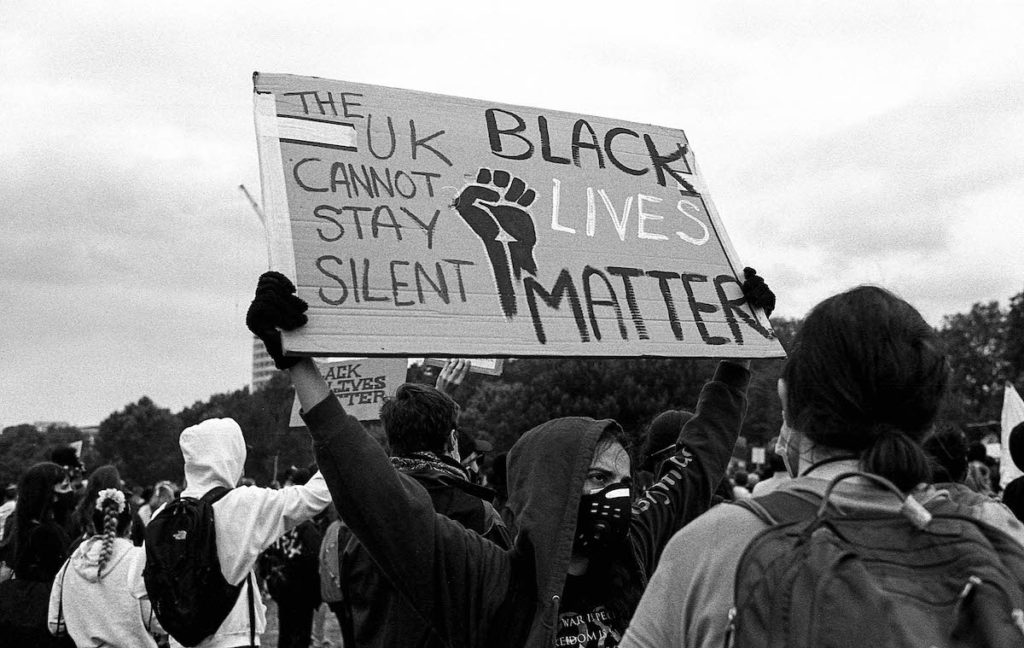

In the UK too, racism rears its ugly head in both covert and overt ways. “It is deeply embedded in our institutions, foundations and psyche—our lived experiences are debated and disputed,” says Bangura. “Racism in this country is deeply entrenched as a matrix, a series of technologies, a meticulously designed system working to subjugate all who are not white.” Conversations about race in the UK are also often inextricably linked to nationalism—with racist remarks and attitudes often being passed off as patriotic. “This kind of narrative is dangerous, it passes the buck on to the USA,” she says. “Wake up, the UK is a deeply racist society.”

It’s been 6 years since the BLM protests in response to the death of Michael Brown, Eric Garner, Tamir Rice and countless other black Americans at the hands of the police. “It’s disheartening that we still have to say something as simple as black lives matter,” says Bangura. “All these times before it felt like anger could cause real shift, real change, yet here we are. I don’t know if it is the global pandemic that has exposed the deep inequalities of our societies and exasperated existing social tensions, disparities and injustices—but this time feels like it could be different. News of the dismantling of the Minneapolis police gives me hope.”

Esajas agrees. “Speaking for a non-American context, the biggest change for me is the engagement in Dutch society—the change in types of conversations, the discussions by politicians etc.” he says. “I remember in 2016 there were barely 300 people at the BLM protests in Amsterdam’s Dam Square,” he muses. “The authorities (unofficially) estimate 14,000 people showed up on June 1st.”

When asked what they make of the increased “violence” in today’s protests, both Bangura and Esajas are quick to mention the importance of drawing a line between destruction of property and destruction of the black body. “There will always be people who care more about the burning buildings than black lives,” says Bangura. This shift is significant. The change in narrative around using non-peaceful methods of protest, from looting corporations to property destruction is new. “I don’t see this as violence,” says Esajas. “The system is violent against black people on a daily basis,” he continues. “I think I will side with the thoughts of Malcolm X: self-defence is intelligent.” And fighting for black lives is self-defence.

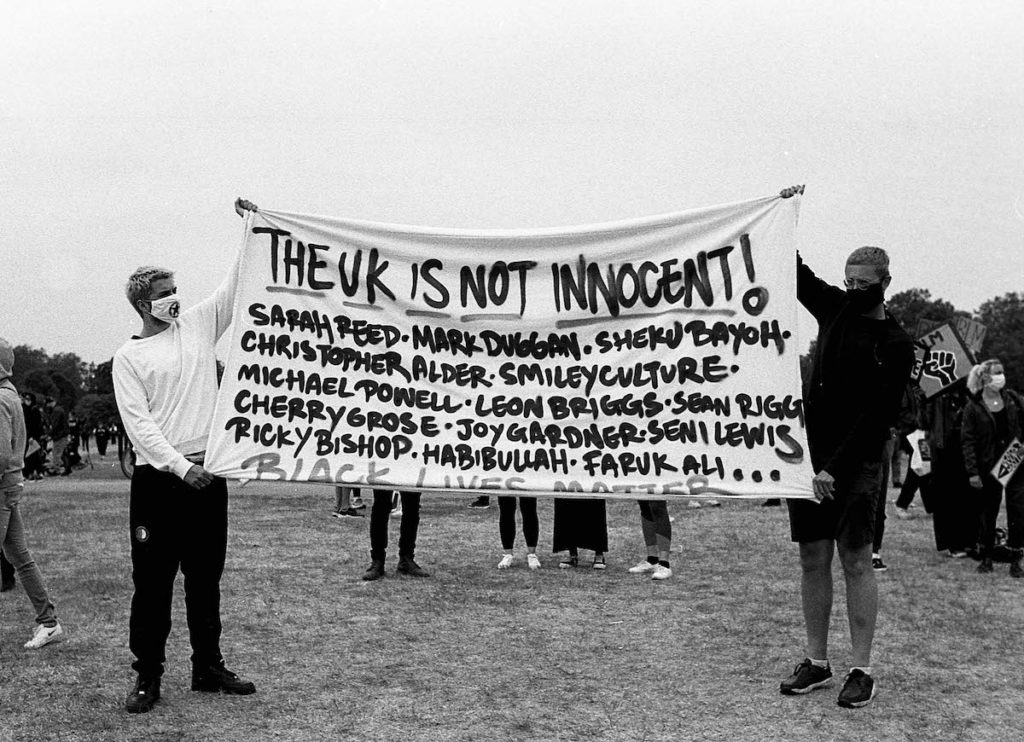

We might not hear as much about police brutality in European cities but that doesn’t mean it doesn’t exist. Rashan Charles, Edson Da Costa, Sarah Reed or Sheku Bayoh are a few names that will be remembered in the UK, but sadly there are so many more that won’t. It isn’t just physical violence black communities face but they are also more likely to be stopped and searched, arrested, charged and convicted. Systemic and structural racism is deeply embedded in our backyards too and Esajas gives me a great example of how backwards our system really is. “Can you imagine that I was debating the diversity manager of the police—a white guy—who doesn’t even acknowledge that institutional racism or racial profiling exists in the police framework?”

So where do we go from here? How do we keep the momentum of these protests from dying out? “Follow the vast array of black thinkers, doers, creatives, commentators, businesses, writers who have carved space for themselves out in the world, particularly online,” Bangura advises. “We have always been there, pioneering culture and leading these conversations, even when nobody else was watching or listening.” We already know that mainstream media has—problematically—kept the voices of BIPOC people in the periphery and brushed conversations deemed too ‘radical’ or ‘progressive’ under the carpet. So we must actively search for the alternative sources of news. “Many generous Black people, including myself, have written and compiled resources for all to equip you with the language you need to be courageous now and in the future. Get up and go and use those resources, find out more and do something. No excuses anymore.”

Photography LOTTIE MAHER