I’ve always had natural hair. For most of my childhood, my hair was either in two bunches, Bantu knots or cainrows. It was never straightened—not even for special occasions—neither chemically nor with straighteners. I didn’t even have braided extensions.

For the most part, I liked my hair. I liked that it looked like my mum’s. I liked going to Jamaica and getting it plaited with beads on the ends—I liked how they would jingle together, making music. I liked sitting between the knees of older girls and watching TV as they cainrowed art onto my scalp. This wasn’t a service I paid for; they did it because they loved me, and the styles were endless. Through their fingers, they told me my blackness was beautiful and my hair deserved love.

I don’t know exactly when I fell out of love with my hair.

Of course, I always had a pang of envy for the girls with straight straw-coloured hair in school—before I could even put into words the suffocating weight of European beauty standards. Like many black girls growing up in the UK, the pressure to somehow achieve long, straight silk locks grew with age. Last year, a study by the directors of World Afro Day found that 41 percent of school children with afro hair wanted to change their hair from curly to straight. I was no different.

But while all my peers were getting their first relaxers, braids cascading down their backs and some even graduating on to weaves, I still had cainrows, unable to sway my mother. I felt like I was still on training wheels while everyone else was speeding ahead in the Tour de France.

As a teenager, after begging and pleading with my mother, I started straightening it. Then dyeing it. Then dyeing and straightening it simultaneously. At this time, I was blissfully unaware of the dangers of dyeing black hair. Earlier this year, a landmark study published in the International Journal of Cancer revealed the dangerous link between permanent hair treatments and breast cancer—a risk that’s over six times higher in black women compared to white women.

To be honest, I’m surprised I still have hair left on my head. Naturally, the result of the dyeing and straightening was not, as I had envisioned, long, silky, flow-in-the-wind hair. But it was the best my Afro hair could do. In the back of my mind, I told myself it was my hair and that’s all that mattered.

And then around 16, I found the flourishing natural hair movement.

Online, I learned about TWAs (teeny weeny Afros) and co-washing. I learned what hair type I had and how to braid my own hair. I discovered an industry valued at an estimated $2.5 billion, and I watched as black people threw out their relaxers, shaved their heads, and started anew. It felt like a satisfying exhale. The natural hair movement was a way to reject Eurocentric beauty. It originated in the US, mainly in online spaces during the mid-’00s and slowly spread globally throughout the African diaspora.

But quickly, comfort turned to stress, as I discovered the online movement wasn’t as much about self-acceptance as it was about hair manipulation, texture discrimination, and length checking. I ended up ensnared in a web of videos telling me how to deal with my shrinkage, near impossible ways to grow my hair down my back, how to get defined ringlets and curls, and slick baby edges down.

I was stuck. While I had become disillusioned with the natural hair movement, I also felt that accepting straight hair, wigs, and weaves was somehow ‘bad’. I had read about the exploitation that much of this multi-billion dollar industry is built on—with some women in Vietnam being offered as little as the equivalent of £2.30 for an entire head of hair that takes years to grow.

So I started wearing box braids and twists; I told myself it was because it was a good, protective, natural hairstyle for your average lazy black girl who couldn’t be bothered to do twist-outs (which it is). This might have been the case the first time I got braids, but I soon became dependant on them; I secretly enjoyed the length of them and the way they framed my face. Pretty quickly, the days I had my natural hair out between braids became shorter—until they didn’t exist at all. I forgot how to look after my own hair as box braids became my crutch.

As an adult, I’ve been a bit fearful to veer away to any other style; I know how politicised my hair is. Just wearing it the way it grows out of my head is a statement—and it’s something black women have always been othered for. Yet in the ‘60s and ‘70s, Afros became a symbol of the black power movement; people were reclaiming their curls in the earlier incarnations of the natural hair movement. But even after the renaissance of the movement, black people still have to put up with hair discrimination. Whether you’re a child facing exclusion from school for protective hairstyles, or you’re a celebrity like Zendaya receiving racist comments for wearing faux locks to the Oscars in 2015—our hair rarely can just be hair.

In Western society, it has seldom been synonymous with the pinnacle of beauty. Just typing ‘beautiful hair’ into Google Images sends back pages and pages of results of women with long, flowing, straight hair washing over my screen. It’s so difficult to not internalise that. And now watching our hairstyles appropriated and lauded as fashionable, by non-black people, when the very same styles on us are seen as unprofessional or brash, is frustrating.

Through long talks with friends and loved ones, reading and educating myself about my hair, now I’m unlearning and relearning—and I’m in a place where I’m ready to explore. Now there’s no art I appreciate more than wig-making—the precise plucking of the hairs on the lace front to create a natural-looking hairline, and the gentle slice of the razor to obtain baby hairs; co-opting got2b spray and using it to secure the wig; neatly dyeing knots in the fabrics to match your scalp before blending with concealer. Wig-making is a true talent that continues to showcase the creative genius of black folks.

But really, it shouldn’t have taken me so long to realise. Growing up—like a ritual—my friends, cousins, and aunties were always switching up their hairstyles. Going to visit my family in Jamaica last year and being in a country where everyone looked like me, with hair just like me, was a warm embrace. It’s a radical act of self-love learning to love my hair the way it is. Even when it shrinks up, or when it’s dry, or the fact that my hair isn’t dense and thick. My natural hair is forever changing.

We have always been experimental with our styles. From the Himba people coating theirs in maroon clay, to Rastafarians locking up for their religion, even to the ancient Egyptians wearing wigs to protect their shaved heads. Deep in my roots reside generations of styling techniques to protect and adorn my head. I’m learning that, even though our hair will always have ideas, stereotypes and histories attached to it, we have power in choice. I understand now, that when you’re assured of your own identity and blackness, wearing a wig doesn’t mean you hate your hair any more than wearing your natural hair means you love it.

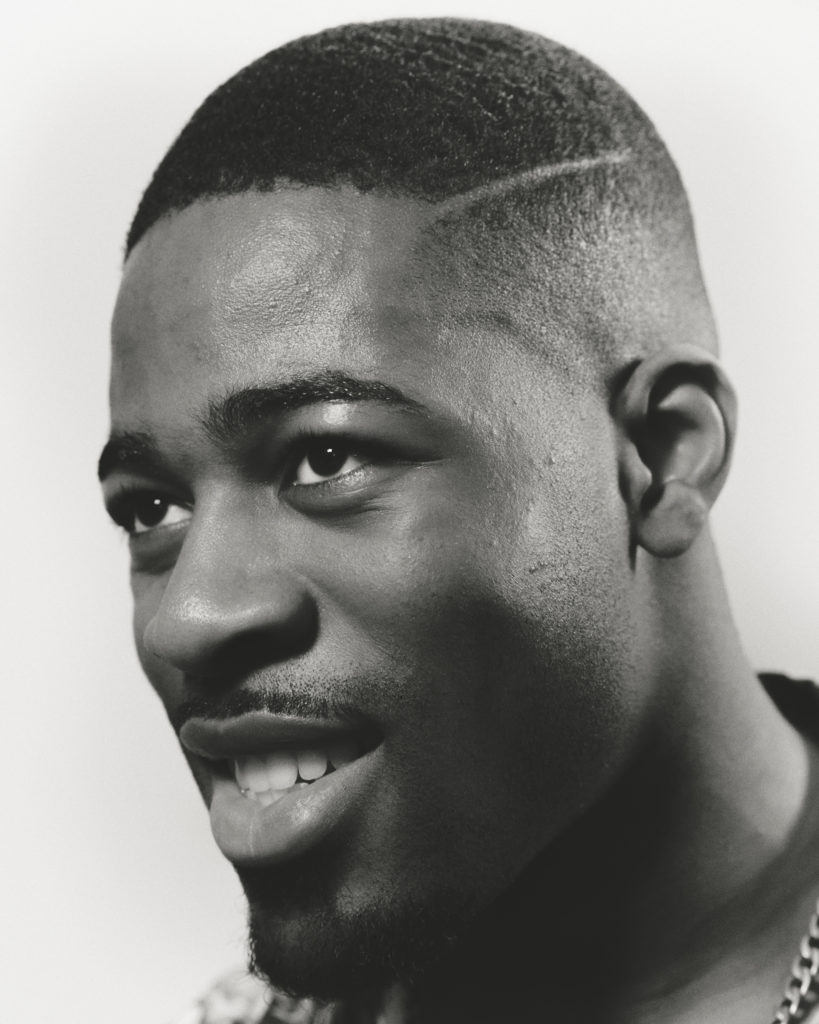

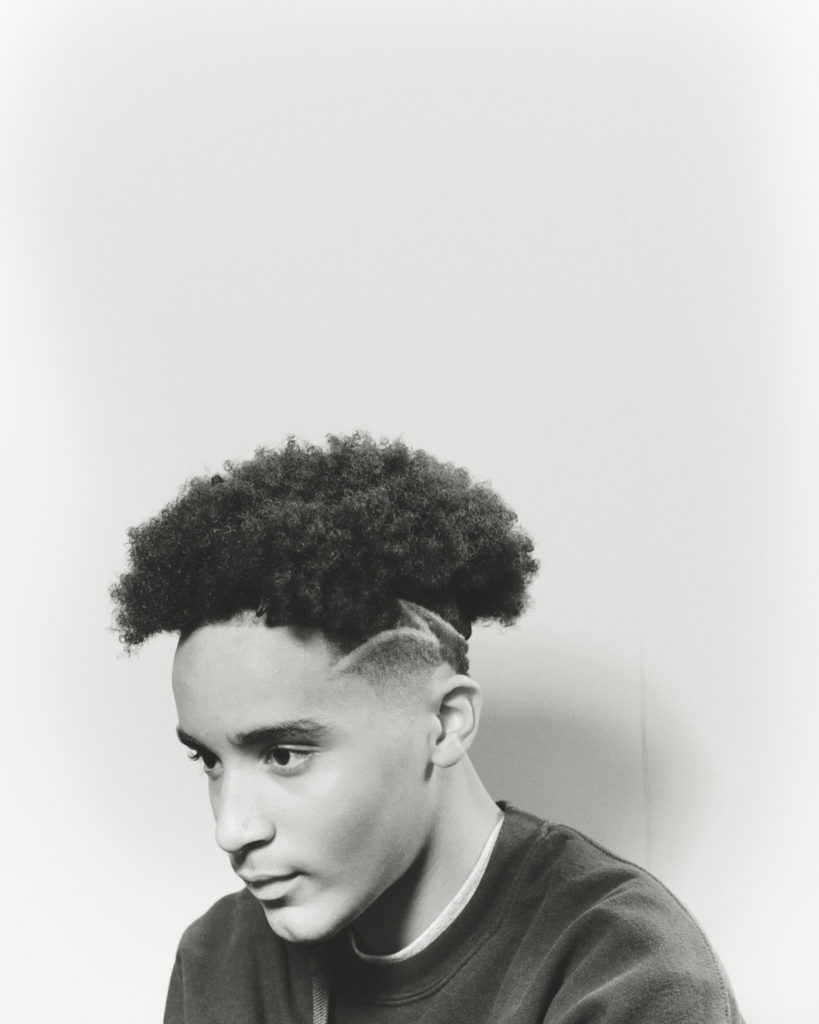

Photography BENNIE JULIAN GAY

Special thanks CURL