Under any other circumstance, this line would entail a spoiler warning, however, if by this point in time you have never seen Jennie Livingston’s masterpiece that is Paris is Burning—Begone! The 1990 film in question documented the lives of New York City’s ballroom scene protagonists in between the mid and late ’80s. Bringing an entire culture, house- and performer-names, as well as voguing and the concept of “throwing shade” into the pop cultural conscience, the 78-minute feature is largely viewed as one of the most important titles of its category. It served as an influence for some of famed gender theorist Judith Butler’s writings, the blueprint for hit TV-series Pose, and is frequently quoted on Drag Race and other now very mainstream, very familiar formats that tackle topics within the LGBTQIA+ universe.

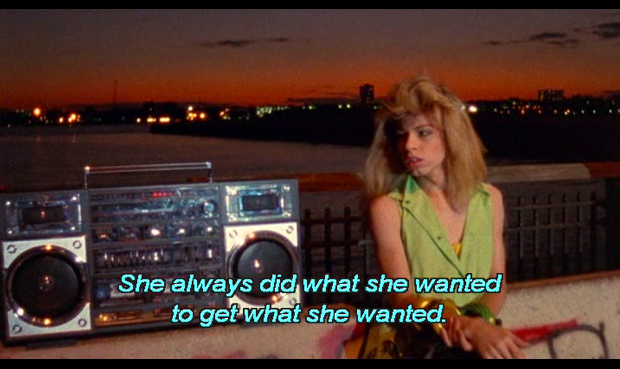

There is plenty more to be said about the severe jolt Livingston’s picture had in- and outside of the queer, predominantly black and latinx community it accompanied over the course of multiple years. But as is so often the case with intricate, impactful art, the devil lies in the detail. Towards the end of Paris is Burning, the plot circles back to Venus Xtravaganza—a young trans woman, entertainer and sex worker. The sunset in her neck, Venus is seen at the piers, asking a bystander to light her cigarette, then switching on a boom box that sits upon the ledge she leans against. From it plays a throbbing, fuzzy synth beat, and a woman’s high-pitched voice cooing “Oooh, Child”. It’s a rather faint, yet recognisable edit of Barbara Mason’s ‘Another Man’, chosen to soundtrack the final scenes of the by-then tragically murdered Venus Xtravaganza. Concluding the arc, drag mother Angie cuts in, blaming her mentee’s risk-affine lifestyle and the overall dangers of being a trans individual in America as reasons for Venus’ untimely death—a death presumably caused by a John of hers, enraged over finding out she was not cis.

Instantly enthralled with the disco-ish production, I tried to Shazam the tiny snippet of song. And while the app failed to provide me with a response to my request, I ventured into YouTube and stumbled upon the exact scene the track is to be found in, with luckily helpful comments as to who it is by and what it is called. I hadn’t heard of Barbara Mason until that point, despite the fact she had a moderately successful career as a singer/songwriter—close to twenty years before releasing ‘Another Man’, that is. Nevertheless, I instantly lost myself in the dazzling, almost tacky instrumentations and half-sung, half-spoken vocals just short of the seven minute mark. Turning and returning to the track every now and then, when in need for purple-lit, nostalgia-inducing white noise, it took me—someone who prides themselves with an understanding and appreciation for lyrical content and its hidden messages—around and about two years to actively listen and fully comprehend the strikingly vile anecdote Mason’s recording chronicles.

A scathing reckoning with a partner she accuses of cheating on her with, well, another man, Barbara describes in unusual detail how she found out about her husband’s double life and why it bothered her so much, defying the conventions of other break-up or call-out tracks of the time and the contemporary—ticking just about every offence-box in the process. “He looked very normal till I opened my eyes / The man I loved and married loves another guy /There’s another man in my life”, she chantingly recollects on the pre-chorus. “Too much sugar and you were little too sweet”, she jokes, referring to the “manchild” she “took from [another woman]”—Karma, perhaps?

The entire song is a minefield when it comes to appallingly problematic lines, peaking in “And there must have been, I figured, a defect / Of not when he was created / But somewhere down the line / Something went wrong”. But it’s the the bit just before the above mentioned “Oooh, Child” that stands out as particularly interesting in the context in which it is shown in the movie: “I had gone out one day and bought me a very, very sexy dress / And opened up my closet and it had disappeared / Lord I hope the man is not wearing my … – Oooh, child”.

As far as my research goes, no one has ever commented interpretations on or disclosed explanations for why, of all songs, this one was chosen for Venus’ final appearance, specifically in relation to its trans- (or at least crossdresser-)phobic sentiments. Browsing through the comment sections, however, reveals a niche-infatuation for this “first down-low anthem,” as one user put it. According to Wikipedia, “down-low” is a slang term coined by American people of colour, to describe (primarily black) men who secretly engage in homosexual activity despite identifying as straight. Opposite those praising Mason for so sassily and scandalously putting her once-significant other on blast, and memories of how it was apparently once the anthem of a popular NYC urban radio station at the time of its release, others joyfully reminisce over Venus, Paris is Burning, and the two’s respective legacies, awarding the track a paradox notion of pride, empowerment and subcultural relevance. For sure, there is reason to feel offended when looking at, or rather listening to the song now. But so many things, it seems, have we just recently found to be hurtful, when at the time, they may not have been—not to a degree, at least, that we’d offer it any proper attention because it paled in comparison to other, often physical and thus often more traumatic misdeeds imposed onto minorities.

I was not alive during the ’80s. I don’t know what it’s like to have been in the situation Barbara or her cheating partner were in. Bear in mind, too, this was in the midst of the HIV/AIDS-crisis, one of (if not the) darkest chapter(s) in history for the already-ostracised queer community. I can’t retrospectively assess how progressive the track is, but for some reason, to me, it feels radical, forward-thinking even. It’s a woman in pain and anger over being betrayed. The things she says are triggering, to say the least, but they’re also to be read as stylistically conversational, things one would say in desperation, at lack for answers, in affect, to someone worthy of trust. It somehow resonates with me that in that genre of music, at that time, someone would so casually tell of this story. A story probably not all that uncommon, but one many would’ve been too embarrassed by or proud to address on such a far-reaching level. To this day even, it feels very unique, not just in terms of its admittedly cringe-y choice of words, but in its nature as a whole.

I believe it was Netflix’s Grace and Frankie in which one of the characters states she can’t be mad at her once-closeted ex-husband for cheating on her, because he cheated on her with a man. And while I do praise the show for steering clear of homophobe nuances, I disagree. If you’re in a monogamous relationship, marriage even, then no matter who you cheat with, your partner has a right to be upset. Barbara Mason embraced this right, albeit by taking it to controversial extremes, and spoke her mind. Although it ends and is laced with troublesome assumptions, the song switches occasionally, from vaguely tolerant to indifferent towards the fact that there was another man, not another woman involved in the triangle. It lends a touch of visibility, normalcy even, to non-heteronormative romantic drama.

So, whatever way you yourself choose to judge this song, I, on my part, am weirdly intrigued, comforted even by it, and can’t help but hold it in high regard as a truly subversive artefact of music history—certainly one worth criticising, maybe even one worth getting genuinely frustrated by, but also one so different from anything at that time and from anything I’m aware of today. And if it offers a long-lasting sense of comfort and meaning to the heritage of Venus Xtravaganza & Co., then I can’t help but sympathise with Mason, her ex and the (almost unheard of) Other Man.

Head Image: Film Still from Jennie Livingston’s Paris Is Burning”(1990)