From disposing of Lena Dunham to ‘cancelling’ Caitlin Moran, Micha Frazer-Carroll shares her journey of unlearning white feminism as a woman of colour.

Like many teenage girls, I splashed my personality on the walls of my bedroom. I plastered dog-eared posters of every film, band, and book I fell in love with to every available surface of my sacred space. Perhaps most memorable was the blue-tacked shrine I created around the circumference of my full-length mirror—DIY printouts of the girls and women I looked up to. This included everyone from my favourite film stars, like Winona Ryder, to writers whose work I pored over at the time, like Sylvia Plath. The jagged-edged scraps of paper—delivered by my home inkjet via Microsoft Word—formed a halo around my reflection, a quiet reminder of who I wanted to be. Like a guardian angel perched on the protagonist’s shoulder, this little collage of faces was my guiding light.

Looking in that mirror now, I don’t recognise myself. Frozen in a strange moment in time—both in my life and in pop culture—those crumpled images read like a who’s who of the feminists that failed me; with PR ‘blunders’, ill-advised tweets, or art they had gone on to create that revealed their politics were not what they were cracked up to be. Awkward and confused, I’m left wondering what happens when our idols let us down? How do we leave them behind?

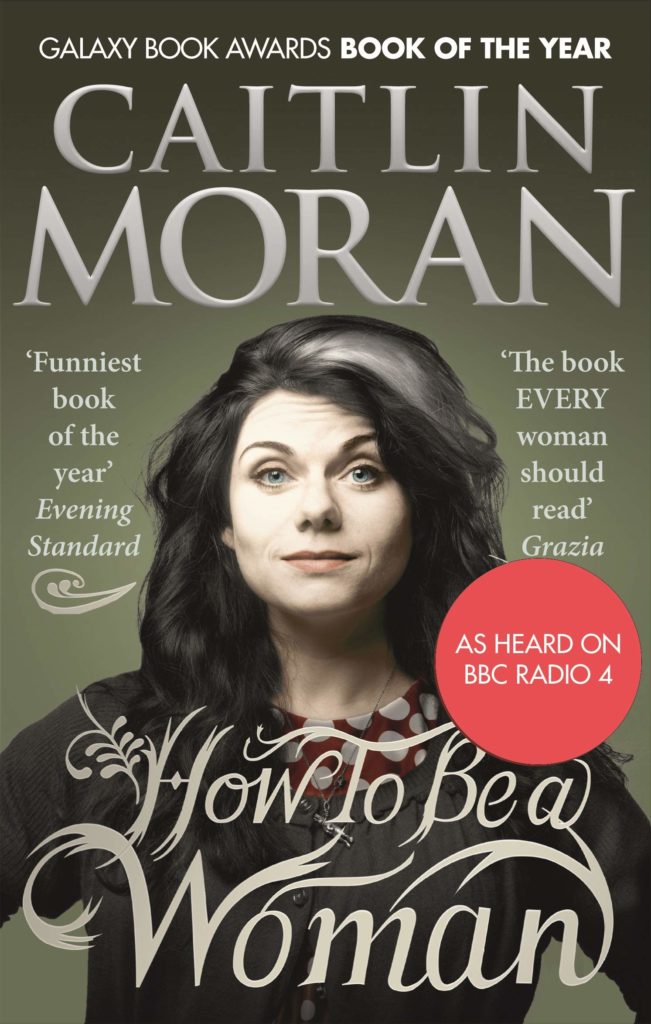

As Caitlin Moran—Times columnist and author of much-hyped 2011 book How to Be a Woman—stares out at me, I cringe. I don’t think 17-year-old me had even read the book when I stuck her picture on my wall, but I knew she was a feminist and, sometimes at least, told half-truths about women’s liberation. She was popular among my most progressive friends and exemplified an early version of the humorous Twitter-feminist persona that’s now common on the world’s most popular microblogging platform. This was enough boxes ticked for my adolescent self, but since then, I’ve come to learn that I’m completely opposed to Moran’s brand of white feminism—a term that describes feminism with a disproportionate focus on the struggles of white women. After moving out of my childhood room and heading off to university, I read How to Be a Woman. I hated it.

One metric Moran used to diagnose sexism was to ask herself: “are the boys doing it?”

“It was the ‘Are the boys doing it?’ basis on which I finally decided I was against women wearing burkas. Yes, the idea is that it protects your modesty and ensures that people regard you as a human being, rather than just a sexual object. Fair enough. But who are you being protected from? Men. I don’t know why we’re suddenly having to put things on our heads to make it better. Unless you really, genuinely like all the gear and would wear it even if you were alone watching EastEnders, in which case carry on.”

In a discussion about Lena Dunham’s incredibly white Girls, Moran said she “literally couldn’t give a shit” about the representation of people of colour on the show. Since these incidents—and countless others—I’ve left Moran behind. This is not what intersectional feminism looks like.

View this post on Instagram

But abandoning is easy, and in the age of ‘cancel culture,’ it can also be dangerous. When I was a sheltered teenager, Dunham was one of the first people to introduce me to the concept of body positivity. I’m no longer in awe of her, but back then, she was a reflection of where my own feminism was at. Wouldn’t it be hypocritical to completely write her off for mistakes she made in 2011, when my feminism was also quite basic at the time? Am I leaving celebrities no room for error? I didn’t see the flaws in feminism because the concept was entirely new to me; maybe it was the same for them.

As I’ve grown as a feminist—thanks to reading the likes of Patricia Hill Collins, Judith Butler,and Audre Lorde, to name but three—I’ve come to look at my past work the same way I do those women on my wall. I started writing when I was 18, and six years and hundreds of articles later, my feminism has evolved. My views have changed—they’ve become stronger and more intersectional—and with it, so has my work. Looking back at certain articles or blog posts makes me cringe, and I wish I’d known then what I do now. But life is a learning curve, and just as I grew, I know it’s important to remember that my idols are able to grow too.

View this post on Instagram

When a bunch of Stormzy’s homophobic tweets resurfaced after six years, he apologised. He explained he was still, essentially, a school kid at the time, and many of us forgave him. I believed—and still do—that people should take responsibility for their words, but equally that many of us internalise harmful, oppressive, and violent ideas as a result of being socialised in a harmful, oppressive, and violent society. It’s complicated. Equally, we’re protected by privilege, as Tavi Gevinson pointed out in her 2017 apology—a response to her decision to publish an article on her website that claimed you could remain friends with a Trump supporter. “I am also protected by the privileges of being white, cis, straight, able-bodied, and a documented citizen,” she wrote.

“I didn’t account for how my privilege would inform my decisions. I’m sorry I was not vigilant about not normalizing the bigotry and discrimination that Trump not only represents but is putting into action, and that his supporters— explicitly or by association—endorse. I’m sorry to everyone who was marginalized and/or hurt by yesterday’s post and by the language we used to share it on social media. I am thankful that you voiced your opposition, as much as I wish you hadn’t had to in the first place.”

Gevinson—a mirror image of mine who has been able to stand the test of time—was 21 at the time. She didn’t attempt to cover any of her tracks while apologising—in fact, she posted screenshots of every single rightfully angry comment in response to the article. To me, this is what accountability, and intersectionality, look like. It’s one of the reasons I have always kept Tavi around. Cancelling Moran, however, I don’t feel bad about. As she continues to hash out tongue-in-cheek car-crash columns about Isis bride Shamima Begum’s ‘image problem’, her failings become increasingly hard to forgive.

When I look at the photos around that mirror now, I see both the women who have been relegated to the graveyard of my past idols, and those who I still deeply respect—Angela Davis’ face particularly stands out as one idol I haven’t left behind. It’s sad to say goodbye, but I won’t pretend it isn’t necessary—and I equally won’t pretend I never looked up to them.

The feminists I’ve abandoned are women who seem vehemently opposed to apologising for, or learning from, their previous mistakes—even when they are repeatedly resurrected and dissected on the internet. Meanwhile, I’ve come to believe there are a few things that set the good ones apart: self-criticism, openness, and a willingness to listen and grow.

Most of us say, do, and believe things we may one day regret—that much is unavoidable. But what I now look for in an idol is someone who will rise to the opportunity and endeavour to grow when the chance presents itself.

If you’re not open to expanding your feminism and your politics, why should I be open to you?