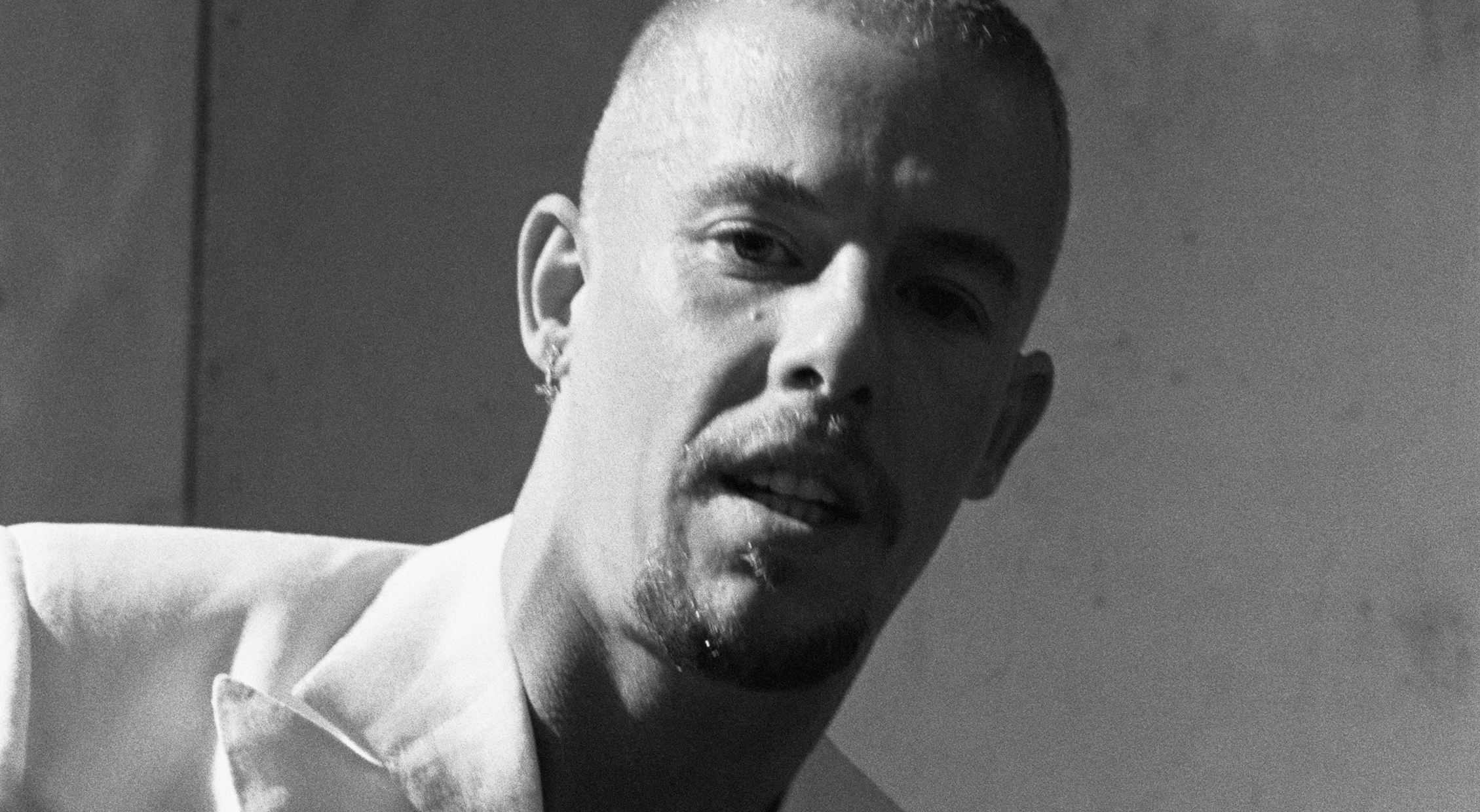

In Lee Alexander McQueen’s working life, determination continually clashed with drawbacks. For INDIE, four of the designer’s key collaborators speak about the long-lasting impact of his inimitable journey.

“That’s me!” Alexander McQueen is quoted as declaring in Dana Tomas’ book on the designer’s career, Gods and Kings. Having just watched a documentary on gazelles, he was reminiscing about the inspiration for his AW 97 collection It’s a Jungle out There—and about his own part in fashion’s searing savannah. “Someone’s chasing me all the time,” he went on, “and, if I’m caught, they’ll pull me down.”

Whether verbally or visually, Alexander McQueen seldom shied away from declaring his discontent with certain parts of fashion as a system, environment and workplace. And within an industry that is increasingly questioning its web of ethics and expectations, those words uttered some 22 years ago—and the designer’s journey itself—still feel remarkably raw and disarmingly intimate, not to mention the unanimous appeal both Alexander McQueen the person and the brand seem to hold to this day. In 2011, one year after his suicide, Savage Beauty, the exhibition dedicated to the late designer by the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York became the museum’s then most popular offering. Just last year, Ian Bonhôte’s documentary on McQueen was released to impressive box office numbers, while two feature flms—one a biopic by Andrew Haigh, the other focusing on his relationship with Isabella Blow—are still in the works.

Few designers have creative and personal paths so intrinsically linked to the push-and-pull of fashion, to its soaring highs and shattering lows. From his haunting graduate collection at Central Saint Martins in 1992—bought in its entirety by soon-to-be confidante Isabella Blow—to the sartorial tales of tenderness and torture that he sent down the runway, McQueen’s designs were always heavy with commentary, often accompanied by razor-sharp hints at fashion’s fetishisation of fame, fortune, beauty and the beasts.

Such was the show he staged for It’s a Jungle out There in February 1997, translating the animalistic themes he had previously noticed into nothing less than a creative roar—think models with bushy manes and oversized black cat eyes, blazers with pointed shoulders or horns erupting from their backs. Having just been named chief designer at Givenchy, and with a mildly received first haute couture collection for the French fashion house still in rearview, McQueen wasn’t there to play it safe—or by anyone’s rules, for that matter.

VOSS, the SS 01 show attached to his collection of the same name, is infamous to this day for its candid commentary on the industry’s weakness for voyeurism and its often-narrow understanding of beauty. Seated in front of a mirrored cube, attendees were left staring at their own reflection as McQueen deliberately delayed the beginning of the show. As the stage finally lit up, haunted models appeared, observable through the cube’s walls yet unable to see the staring audience themselves. Afterwards, another cube was revealed, and inside: an even more transfixing scene, modelled after artist Joel-Peter Witkin’s photograph ‘Sanitarium’, which showed writer Michelle Olley laying naked on a chaise-longue covered in moths, her face hidden behind a mask with a breathing tube attached. With sanity and vanity colliding in their most extreme forms, McQueen couldn’t have been more poignant.

Three years later, his SS 04 offering, titled Deliverance, famously touched on the breathlessness a career in fashion can often entail. Referencing Sydney Pollack’s film They Shoot Horses, Don’t They? about a fatal dance marathon, McQueen similarly had models and professional dancers compete dressed in his new collection and desperately trying to keep up until the last contestant collapsed on stage.

Fashion did, and certainly still does, often feel like this race—not just to McQueen, and not just if you’re an infamous young talent juggling the design directorship of two labels. With a pressure for both presence—parties! Fashion weeks! Social media!—and pulsating ideas being put on designers of every age and in every stage of their careers, maintaining a clear head and a clean vision can become increasingly difficult. Yet the industry seems to still have an ambiguous relationship to weakness and imperfection, an astonishing reluctance towards anything less than superhuman.

In light of this issue’s theme, four of McQueen’s long-time confidantes told us about the invaluable lessons from their journeys with the late designer—and why his personal one continues to be so crucial for fashion and the people shaping it.

SIMON UNGLESS

From studying with Alexander McQueen on the fashion MA course at Central Saint Martins, to working on a number of his early collections, to living above the designer in a house he rented in Tooting, London, Simon Ungless was one of the designer’s closest friends and collaborators. He continues to be an advocate for boundary-pushing fashion, currently holding the role of fashion director at the Academy of Art University in San Francisco.

“Lee was completely different to the other students in our year at CSM. His work was different, and his outlook and attitude were different. He was devoid of the ‘rules’ we had all been taught in school but was very hungry to learn and so was totally interested in everyone else’s work and very vocal. He had opinions on everything, which was also out of the ordinary. Working with Lee was a partnership, we would work together on a project, learning from each other. We lived and worked in the same place and making things was just what we did. It was a fun exploration into just doing it, trying things, experimenting. We didn’t have a dress form for a while during the Taxi Driver time. Lee would drape and cut on me, quickly sew up the garment and then I’d dip it in latex, or resin, or print it. It was immediate, potentially unplanned and completely enjoyable. Very often there was no planned outcome, just doing, seeing how things worked.

Back then, the fashion industry filled me with excitement and wonder. Ever since I can remember, I wanted to be part of the magic of it all. Recent years have felt incredibly toxic. Too much regurgitation of ideas, way too many products, and far too much hype. Fashion has become a monster eating itself, too many collections, too many fashion weeks and too many ‘designers’ who aren’t really designers. Too many investors needing a result. Everything today is outcome driven and dollar driven. It leaves very little opportunity for chance. Lee was allowed to develop at a realistic rate, not having to prove sales for several seasons, allowing him to mature as a designer. One lesson the next generation can learn from him is to say no. Say no to publications, say no to stores and say no to celebrities. Lee was very clear on this. Have a clear vision of who you are and stick to it. Today’s tendency is to say yes to everything, have every piece of trash sat in your front row and make everything about the bullshit and not about the clothes. But I do see a group of new designers starting out that a very clear vision and the skill set… to back it up—Edwin Mohney, Stefan Cooke and Matty Bovan, for example. I hope they are allowed the space and time to develop in real time.”

SHAUN LEANE

Originally trained as a fine goldsmith, Shaun Leane created the still agenda-setting jewellery for the Alexander McQueen and Givenchy shows—including the coiled necklaces of It’s a Jungle out There and life-sized pieces resembling animal skeletons. Leane met McQueen in 1992, and was continuously challenged by him to try his hand at working with new and unusual materials. He was also one of the speakers at McQueen’s funeral on 20 September 2010 in London.

“My initial sense of Lee was his shyness, but even though he was shy, he had a strong underlying confidence in his own being. Lee was part of an amazing zeitgeist where many mediums intersected—music, contemporary art, photography and film. All of this was made possible by his fearlessness to create a silhouette and an idea of fashion that represented the 21st century. For me, one of the most confident and freeing elements about collaborating with Lee was that in his mind and his approach, nothing was impossible. He challenged me to think outside the box and apply my skills to a different medium to create the pieces we did. He gave me a creative platform on which there were no boundaries; Unique creativity comes from the freedom to fail.”

MIRA CHAI HYDE

During the 1990s, the now Los Angeles–based groomer invited Alexander McQueen to live with her in her flat in London’s Hoxton neighbourhood after he moved into the same building a month before, his studio set up in the basement. Hyde quickly became a close confidante, responsible for hair and grooming at his shows, and sometimes even cutting McQueen’s own hair.

“What differentiated Lee’s way of working from other people I have collaborated with over the years was that with other designers, their stylist or creative director would explain the look of the show and what they thought the hair and make-up should be like and then the look would be okayed during the fittings on the boys days before the show. But Lee gave me creative room to interpret his vision. He would come by every once in a while to have a look. I never heard from him ‘this is great’—I just knew if he didn’t say ‘nay’ to anything he was happy. We had fun and we had so much creative energy around us. Now it is more about numbers, it seems, and less about the creative process and the pressures it puts on their creatives to keep producing more and more for the consumers.

I believe the most important lessons we should learn from his career when looking at today’s fashion landscape is that Lee got to where he was through sheer determination and guts. He put himself out there in every avenue in order to get to learn from the very bottom the basics of his craft, every inch of it. You need to learn the basics in order to tear it apart but still make it look like a piece of art.”

ANN RAY

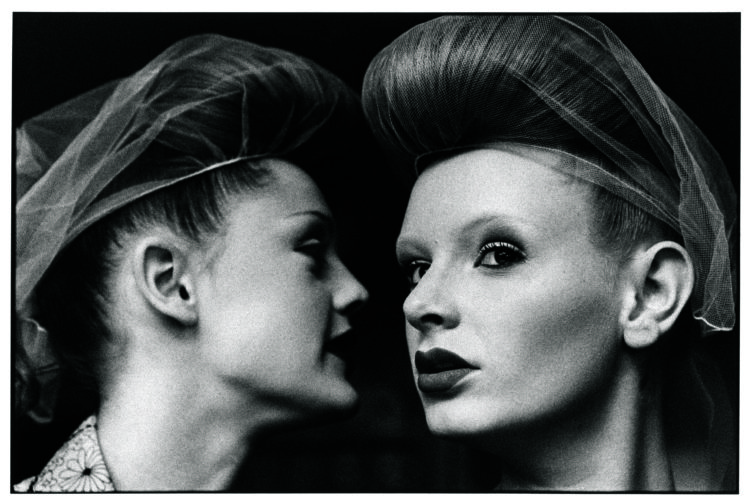

The French visual artist and director collaborated with Alexander McQueen for 13 years in a variety of ways. Ray and McQueen met in 1996 just as he had been appointed chief designer at Givenchy. Apart from her personal projects, Ray is known for these deep connections and collaborations with exceptional artists. Working with McQueen and Givenchy, Ray photographed the creative process of 46 shows.

“People like Lee McQueen are rare and precious. They have a massive impact on whoever has the privilege to get close to them. I always saw him as an artist—based on my first impressions when I met him, as much as on his own words: ‘fashion is just the medium’.

Millions of artists have good, or very good ideas. Hundreds of artists have extraordinary ideas. The difficulty—and therefore the genius—is to make it happen, to give the idea shape and to deliver. That’s what Lee did, as an artist. ‘Genius’ is a word from outside; no decent person can think of him or herself as a genius; Lee certainly couldn’t—he was far too grounded for that.

Creation is a lonely act: Lee surely had a lot to express. However, the result delivered to the audience was the sum of works made by a creator and his team. You don’t do anything alone— there are always dedicated people in the shadow. People who work with you, put you in the light, help and support. So if you want to admire Lee McQueen, you have to admire his team too: people deeply devoted to Lee, like Isabella Blow, Annabelle Neilson, Sarah Burton, Amie Witton, Philip Treacy, Shaun Leane, and myself, to name a few. It’s important to say this, for once, since Lee wouldn’t have gone so far, and would not be remembered today as he is without all these people around him.

As for myself, the figures speak for themselves: for 22 years I have been working for Lee McQueen, in one way or another; thirteen years of his life, 46 shows (!), an archive of 35,000 analogue photographs, that I still manage alone. So… have I been privileged? Absolutely—I would not be the person I am today without Lee and I am endlessly grateful; and has it been wonderful? Honestly, it’s been terrible and magnificent, before and after 2010. Far from easy. I just perform my duty: nobody else has so much material, it’s a responsibility; photographs hold the naked truth, they can’t lie. I can thus pay homage to my friend through books and exhibitions with honesty, dignity and poetry— what I believe is right.

Beauty is simplicity. Lee and I had a simple, beautiful relationship, never altered over 13 years. I only realised how famous he had become after he died. I’m talking about pure fame here, something that leaves me indifferent. What I find intimidating is talent and, in that respect, I had been intimidated by Lee since the very beginning. His journey has to be remembered because it has been a journey without compromise. Lessons in life, for everyone. Not just in fashion.”

Photography ANN RAY