For centuries, sex work has been the subject of extreme stigmatisation. Sex workers have been deemed by society as the bottom of the barrel—complicit in immoral acts and sordid deeds that reveal the darkest desires of the human psyche. And, admittedly, the sex work industry is not without its downfalls. There’s no making light of the horrific human trafficking, violation and exploitation that colours the sex work industry worldwide. But, converse to what the media would have us believe, this is not the whole story. Society fears the unknown. And under the overarching power of the patriarchy, it’s hard to accept that for some, sex work is a liberated choice. But a new wave of sex workers is aiming to contest this pervasive view.

Sex work is work. Being financially independent and following your own choices are by some of the most admirable and affirming actions one can take in the eyes of society—so why is sex work viewed any differently?. The easing of laws around the world concerning sex work has had a huge impact on the industry itself and its clientele. From Scottish sex workers protecting their rights and ensuring safety in the workplace, to Denmark’s openness and visibility in honouring workers, to the US 2020 elections aiming to legalise it across the States, with more open debates and conversations around the topic, our level of understanding increases. Sex workers are finally being given the spaces and platforms to voice their stories and opinions, vehemently fighting their corner and asserting themselves as members of the working world.

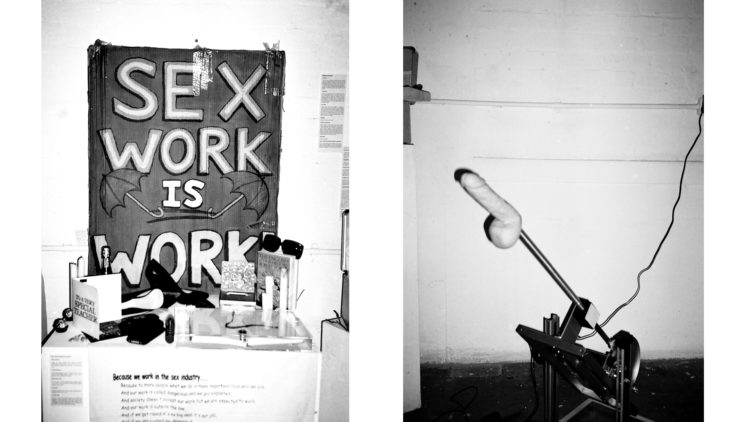

Left & Right: Objects of Desire (2016) Sean Haughton

It’s exactly this ethos that underpins forthcoming exhibition Objects of Desire at the Schwules Museum in Berlin’s Mitte. “An exhibition of sex worker’s stories told through objects” as the museum puts it—this norm-smashing, binary-bending and multi-faceted exhibition is due to run until 1st June (International Sex Workers Day). Having already had an opening show in London, this exhibition comes to the people of Berlin with hopes of garnering the same eye-opening experience.

“This exhibition is important because it is an empirically grounded interjection into hyperbolic debates around sex work,” explains Rori, sex worker and co-curator of the show. “Public discourse around sex work is dominated by one dimensional stereotypes that portray sex workers as either empowered agents or exploited victims. This exhibition disrupts that binary by presenting varied and nuanced stories of sex work—stories told through the objects convey sadness, joy, frustration, boredom, and sometimes ambivalence about the mundane and day to day aspects of the job.”

Objects of Desire (2019)

Objects of Desire (2019)

The controversial Prostitute’s Protection Act, which came into effect in Germany on 1 July 2017, proves there’s a very real need for increased visibility, and understanding, of the ostracisation sex workers face from cultural development. The law called for more control, penalties and regulations, making it mandatory for the individuals to register and identify as sex workers. It’s hugely problematic, and unsurprisingly, the sex work community lashed back with relentless criticism, arguing that this meant they were consistently under extreme scrutiny, in turn making it more difficult to earn money, set up brothels and attract clients. Objects of Desire is the first and definitely most unabashed museum exhibition that will showcase a variety of works and nuanced stories from the sex workers community.

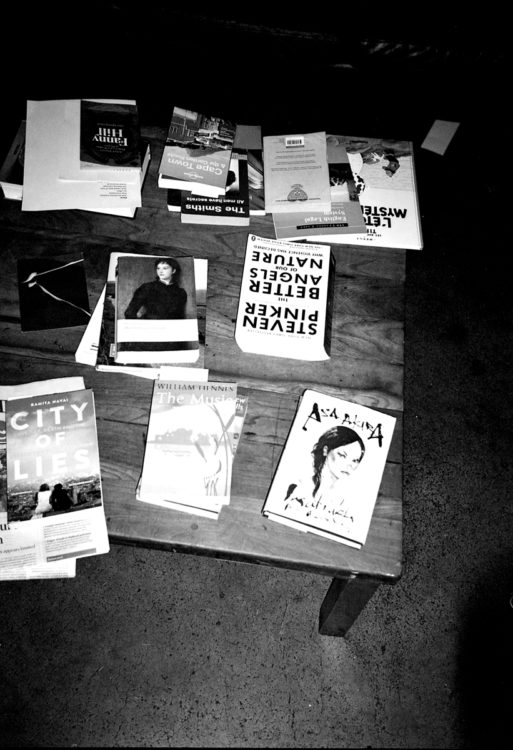

Not only will the exhibition convey and facilitate the message of sex work as work, but it will also display artwork made by sex workers and information gained by carrying out interviews in Berlin over the past year. From performances on fetishisation of national identity to mixed media installations on astrology, this labyrinthine and experimental show is a true homage to individuals of this industry. The collaborative project, primarily led by artists and sex workers, examines the social relations present within the industry by dissecting and exploring the physical memorabilia tied to it. Rather than approaching sex work in terms of objectification and the male gaze, Objects of Desire consciously force the viewers themselves to pivot their pre-existing notions on sex work, and to witness it through the medium of miscellaneous objects, photographs, written text and gifts received from clients.

Kitchen Coasters (2016) Izzy Valentine

Kitchen Coasters (2016) Izzy Valentine

“We mostly contacted people through existing sex worker networks,” explains Rori. “Our call for sex worker artists to make pieces for the show was circulated on social media and amongst other sex worker organisations—we also distributed flyers to try to spread awareness of the project” Focused on displaying artefacts that Berlin based sex workers have accumulated over the span of their career, these intriguing objects range from the banal to the bizarre, with butt plugs, bicycles, natal charts, dream water and hand painted tea-lights in amongst the mix. “The idea came out of sex workers chatting about objects, anthropology and art and deciding it would be fun to put a collection of objects and stories in a gallery space. The title, Objects of Desire is a playful retort to discourses of objectification often used to frame sex work”, says Rori. The passing of these objects from client to worker is recorded to highlight to the viewers the materiality connected to sex work, but also the personal stories that we are being given the opportunity and privilege of hearing. Moreover, the exhibition also documents and presents, in one medium or another, snippets of conversations had between sex workers and their loved ones. The exchange between these two groups is highly intimate and accentuates the vulnerability of the discourse connected to sex work.

Cabinet Jam (2016) Izzy Valentine

Cabinet Jam (2016) Izzy Valentine

Ethnography plays a huge role in this exhibition—as an exploration into the culture and people of this sector of society. The exhibition itself is groundbreaking in its aspiration and concept as it ferociously challenges the preconceived stigma of silencing and exploiting sex workers—it does quite the contrary. The Schwules Museum plays a huge part in enhancing this by offering a platform for underrepresented collective like Objects of Desire to showcase the talent and stories of creators from different backgrounds. Objects of Desire gives these individuals a voice and humanises them in a way that only their stories and representations of them can. Rori goes on to tell us that “on a broad level, we hope the exhibition will increase the visibility of sex worker narratives so that public opinion, media depictions and legal frameworks occur within a context where many different sex workers narratives are heard. In relation to the specific German context, the exhibition includes stories from sex workers in Berlin about their experiences of registration under the new law. We hope that people will come away from the exhibition with a greater understanding of what the law means for sex workers and a greater openness to listening to sex worker organisations as the experts on legislation that directly affects them.”

Objects of Desire (2016) Sean Haughton

Objects of Desire (2016) Sean Haughton