William Ndatira — perhaps better known by his Instagram handle @williamcult — is a designer and commercial artist who helms his own brand, CULT11AD, and has collaborated with fashion’s biggest names, such as Gucci, Fantastic Man and AnOther Man, to name a few. But while he uses his social media influence to platform other artists publicly, privately Ndatira battles with the scars of a nearly life-ruining drug habit. Born in Burundi, raised in Switzerland and now based between London and Johannesburg, the artist’s journey in life has been much more than simply a geographical one. Here, in his own words for INDIE, Ndatira recounts his battle with drugs, addiction and finding his way out of the darkness, into the light.

It’s a strange form of darkness whose presence you can feel, yet which does not overshadow your life. The memories of being a drug addict are still fresh and they keep me from going back; it’s been almost ten years but the darkness still haunts me.

When I think about doing drugs or drinking, it’s not the good times that come to the fore; it’s not the fun times, parties and club nights, but the tail-end of my addiction: it’s the rock-bottom moments, the nights on a cold prison floor, the desperation of getting heroin or cocaine; it’s driving high on painkillers and alcohol, crashing into the back of cars in peak hour traffic, and the loneliness and strange moments where I had no friends, freebasing cocaine in a flat with two cats. It’s a door I can open at any moment, any time I am offered drugs or alcohol.

The person I am now does not recognise the person I was; I’m almost afraid of that person. It’s a strange thing to be scared of yourself. I know the thief, the liar and addict in me is a very short way from the person I try to be every day in recovery and sobriety, the side of me which is now honest, law-abiding and caring. The side of me that’s been given a second chance at happiness.

In order to appreciate and nurture my current life, I have to take ownership of all the fucked up things I did or would do if I opened that door again. For a long time, I didn’t want to think about the person I became. But I can sit and close my eyes and take myself back to being in Johannesburg surrounded by the police, a drug dealer on the floor in a hotel lobby, his leg bleeding from a gunshot wound. I am waiting for my chance to run out, drugs hidden in my underwear, dogs sniffing around the lobby while I try to remain calm and head for the door.

I can sit and close my eyes and instantly be taken back into the court room waiting to see if I will be sentenced to 15 years in jail after being arrested. I was not; the judge realised I was an addict and not a dealer. I was sent instead to rehab. But that fear and anxiety of my life hanging in the balance still remains with me.

Coming from a family of addicts and alcoholics, the fear of addiction had always been there. I’d held back in a very controlled way throughout my teens, giving myself rules like: no smoking pot before sunset; drink in moderation; avoid taking ecstasy at raves with my high school friends. Those basic rules helped me through high school.

Then, the experimentation started at 19 — a whole summer of taking acid and ecstasy. I had a good time. My friends were surprised by my decision but I felt I could do it because I was going off to college.

Later in college I met a guy. We dated and started taking heroin together. At first, his life didn’t fall apart and neither did mine, as I had expected it might. But soon enough I couldn’t just do it on weekends, I needed it to function during the week. With time, it became harder to fight the addict in me.

Something I rarely acknowledge is that a part of me felt a huge relief in embracing my inner demon. One of my biggest fears was becoming an addict but I embraced it. That seemed like such a crazy thought process to me that I never discussed it with my drug counsellor in therapy.

I remember the exact day it happened: my best friend at the time came round to my place to tell me about her struggle to only do heroin on weekends, recreationally. Common sense would have been to get help but instead, we decided to say “fuck it” and take heroin everyday.

The problem is when you embrace your fears, they do not embrace you back lovingly. I didn’t know my life would get so fucked up. In hindsight, if I had known the pain I would cause to myself and others I probably wouldn’t have done it.

Once my addiction took over, it wasn’t a conscious decision to embrace my fear but the physical, emotional need to get drugs in my system at all costs. That need, in my case, took precedence to all the basic values I’d been taught growing up in a religious environment: you shouldn’t steal, shouldn’t lie, shouldn’t self-destruct. Basic emotions, like shame and guilt, flew out of the window.

It’s taken me a long time to rebuild trust, to rebuild my self esteem and to make amends; to ask for forgiveness from those I hurt and pay back what I took. But the best apology is to never do it again.

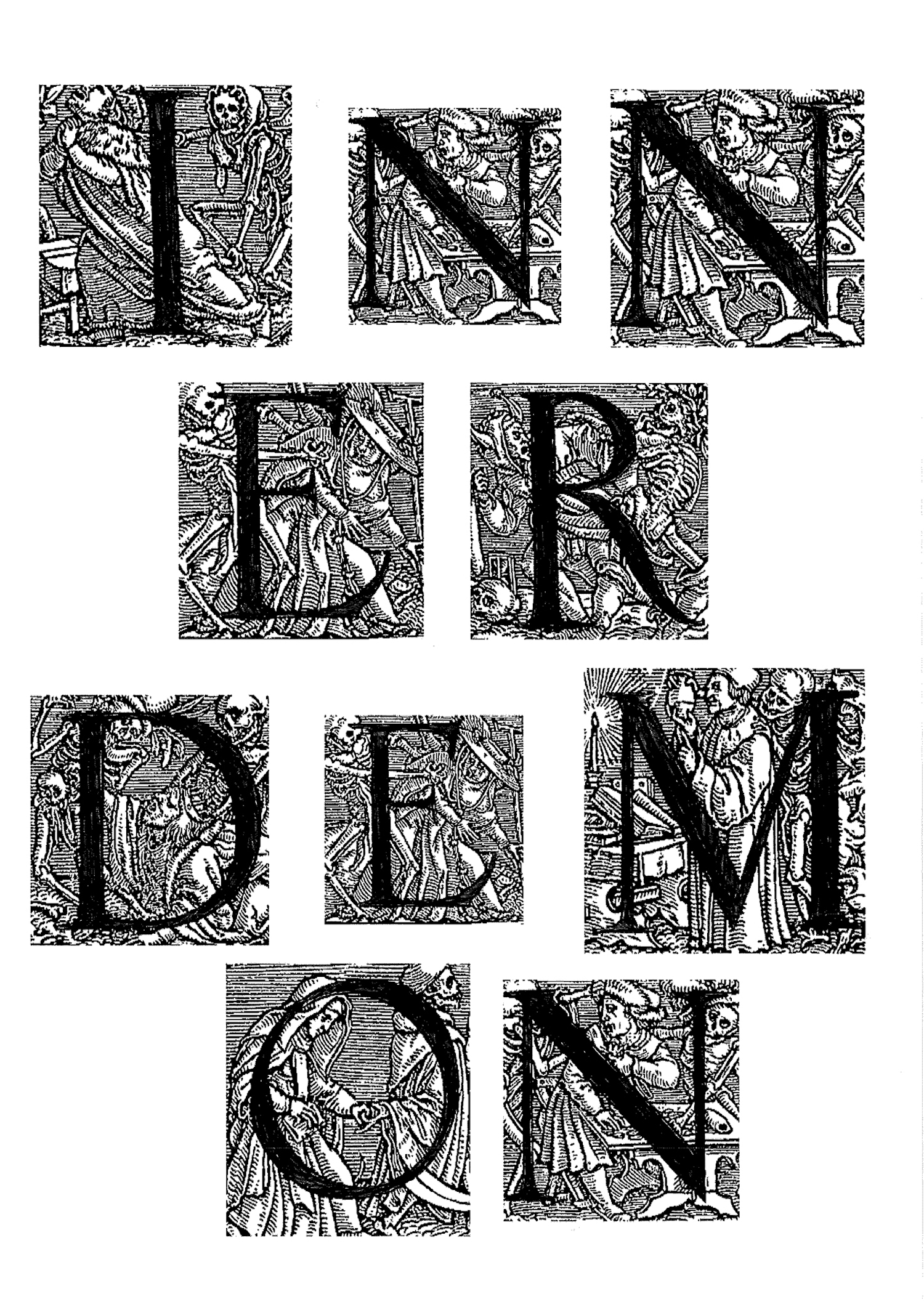

The closest demon I can compare being an addict to is the demon called Choronzon. Choronzon appears in the writings of many magicians and occultists, such as Aleister Crowley, John Dee and Edward Kelly. He is known as the demon of chaos and destroyer of ego. The demon can take on any form and usually takes on an identity that is representative of the individual’s fears and issues. For me, that was addiction.

Getting clean and being in recovery is teaching me a new way of being and a new set of values: honesty, self-esteem, meditation, patience, empathy and a whole host of tools that are necessary to deal with the stresses of life. Because bad things still happen in life even once you’re clean and sober: loss of jobs, breakups and, sadly for me, my brother’s death. I had to learn not to say “fuck it” and use drinking and drugs as a coping mechanism. I had to learn a better way of living and not revert to my old self-destructive ways. That’s the positive outcome of 15 years of drug and alcohol addiction.

To use that cliché sentence: I stared into the abyss and it stared right back and took a piece of me. But it also left something good behind. Although facing your demons can have a positive outcome, I wouldn’t recommend it because it could end in jail or death.

I know I carry both a light and dark side — we all do and we always have a choice of which one to indulge. It’s a choice I have to make each and every day. I guess you could call that coexisting with your inner demons.

Text, photo and artwork by William Ndatira

Taken from INDIE NO 61, THE DARK ISSUE – get your copy here.