Art world it-boy AMOAKO BOAFO and Tate curator OSEI BONSU on sky-rocketing, social media, and celebrating Blackness.

When people talk about Amoako Boafo, they often speak in a kind of cosmic hyperbole. He’s the art world’s newest “star,”his rise has been described as “meteoric,” his auction prices are “astronomical.” In February 2020, the Ghanaian artist’s The Lemon Bathing Suit sold for an unprecedented $880k—more than 13 times its high estimate. Barely ten months later, Boafo’s rendering of the model Baba Diop sold for over 1 million US dollars at auction, breaking the artist’s record. This year, three of his paintings were actually, physically, sent into space. But what makes Boafo’s work so remarkable is in some ways the antithesis of astral: its unmistakable tenderness—resolutely human, irrefutably down to earth.

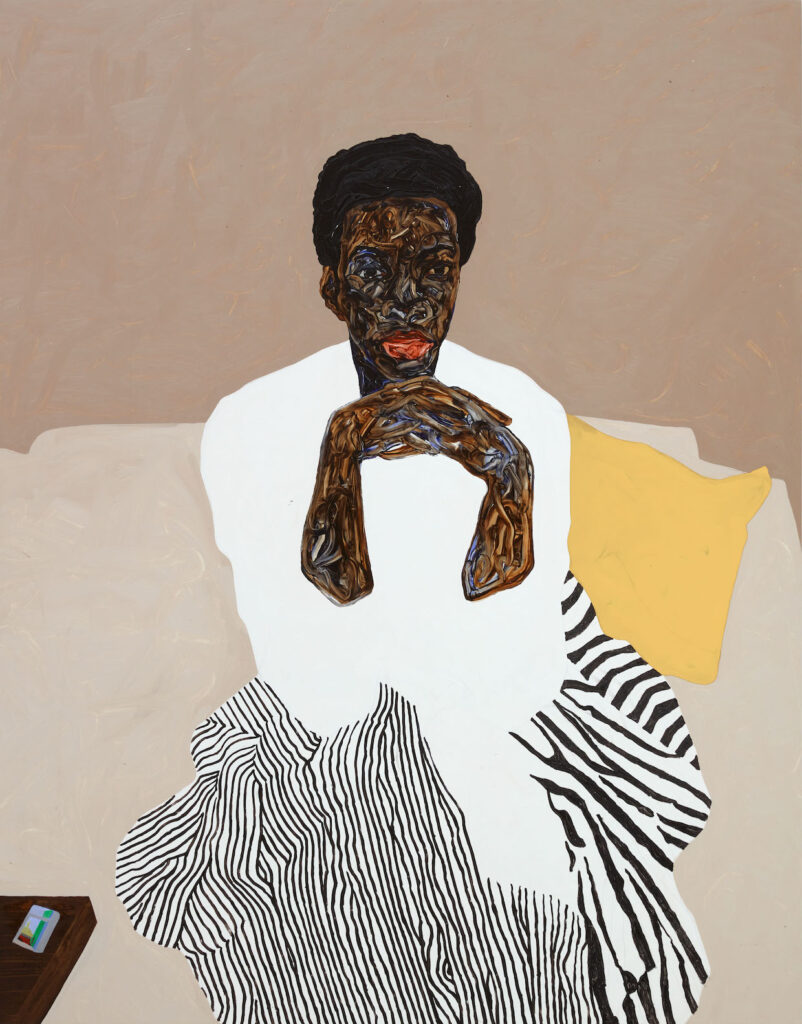

Like much of his fast-growing fan-base, Osei Bonsu, Curator of International Art at Tate, first discovered Boafo online, and was struck not only by the candure of his colourful portraits, but by the artist’s distinctive visual language—a sculptural technique of rendering skin in paint using his fingers—his celebration of Blackness, and philosophical inquisition into capturing the soul. “My initial impression was: here’s an artist who’s going to embark on an incredible journey,” he remembers.

That journey has come on thick and fast.

In 2014, Boafo was living in Accra, struggling to sell paintings for more than a couple of hundred dollars apiece. Later that same year, after moving to Vienna with his partner, artist Sunanda Mesquita, he enrolled at the Academy of Fine Arts, and began painting portraits of himself and other Black creatives in his new community. Through word of mouth and the power of social media, news of Boafo travelled fast. Kehinde Wiley came across his Instagram and connected him to his ‘people’, Mariane Ibrahim and Roberts Projects jumped to represent him, and Kim Jones approached him to collaborate on Dior Homme’s SS21 collection. Boafo’s has become one of the buzziest names in the industry—and the art world cognoscenti are clamouring for a place in his orbit.

Artnet’s Nate Freeman called Boafo’s ascendance “cruel.” Its acceleration has seen the artist quickly confronted with the darker side of an industry known for undercutting artists for financial gain. Seeing his work flipped for profit by those he trusted, Boafo has grappled with artistic autonomy, and has been forced to come to terms with art as a ruthless industry, as well as an outlet for creative expression. But, in tandem, he’s also paving the way for a different kind of art world—one that’s more accessible to those historically written out of it. His success has inspired a new generation of Ghanaian painters, and the international art industry is paying attention. In Vienna, he and Mesquita co-founded WEDEY, a non-profit initiative centering QTI/BIPoC artists. In Accra, where he returned over lockdown, Boafo is building a residency in an effort to continue improving art education in Ghana and foster talent on home soil.

When Bonsu and Boafo meet on Zoom ahead of his second show with Roberts Projects, the two discuss community, Kim Jones, and the key to effective, tangible industry change.

OSEI BONSU: I think you’re an artist whose work, as soon as you’ve encountered it, leaves a strong impression. Whether it’s aligned with one’s personal tastes or interests is not really the question— for me, it was more about the confrontation with your aesthetic, and the kind of language that is entirely your own. I first saw it on Instagram. Even pre-pandemic, I think most people’s art world experiences were being filtered through the lens of social media.

AMOAKO BOAFO: I guess my work has always been out there. I used Instagram as a gallery space when I didn’t have a gallery. Having people press the like button gave me the reassurance that my work was well received—even if it was just two people. And then to have followers like you liking and commenting on my work— knowing what you do and the voice you have in the industry, that was a big deal.

OB: In regards to your ascendance, I think a lot of people credit your success to social media, when in fact, your paintings are real paintings. They exist in the world as physical objects. Painting is about texture and surface, and creating a physical impression, which is compromised somewhat when it’s mediated through the digital as a fleeting image. You’re someone who shares often on social media, and you have a really dedicated following. Do you feel something gets lost in the experience of only looking at your work on social media, as many people often do?

AB: Of course you lose the ability to see the texture and how lively it is, but I like it in a way, because it surprises people when they see my paintings in person. When you see it digitally, you have a feeling of what it could look like. I always have people saying, ‘I like your brushstrokes.’ I’m like, ‘I’m pretty sure you’ll have a different way of seeing it if you see the work in person, because this is not really a ‘brush’—you can’t see the brush moving.’ When you see the movement, it makes you think more about sculpting. I like that when you see the work in person, it’s like your first encounter, even though you already know the work. It’s a completely new work.

OB: There’s something very profound about the way you do that. When I think about Black figurative painters, or painting around Blackness before what you started doing, there was very much this idea that a painter was working in dialogue with the entire tradition of Western painting. I think the reason your work leaves such an impression on people is because the language of portraiture it uses is somewhat reflective of the way we represent ourselves on social media—where you get to choose your background and how you perform for the camera. There’s this very strong relationship to photography that is helping to push the medium forward—because you’re bringing those two worlds together.

AB: The moment you ask someone, ‘can you pose for me?’, everything becomes a bit fake. They have to put on a face they don’t carry all the time. So I will either take pictures when people are not aware, or I just use the pictures they take when they feel comfortable. Most of the time, people tend to do that when they are alone. They show the best of themselves, and then they put it out there. I want to promote that self-esteem and self-confidence.

Green Handbag © Amoako Boafo, 2021. Courtesy of the artist and Roberts Projects Los Angeles, California.

White Nail Polish © Amoako Boafo, 2021. Courtesy of the artist and Roberts Projects Los Angeles, California.

OB: When people talk about your work, they often talk about the sitters being friends, fellow creatives, people who inspire you. I’m curious, was it always obvious to you that those people would be your subjects?

AB: When I started painting, I knew for sure that figuration and portraiture was something I was interested in, because I was always interested in human expression as a kid. My early paintings were of children who reminded me of my childhood, because I didn’t have the opportunity to have someone document mine for me. I only have really vague memories of that time—and most of it is just games.

It was always about community, but when I moved from Ghana to Vienna, it changed. Firstly, because the games and the kids were different, and also because people did not really connect well with that particular series. That’s when I started experimenting with self portraits. I’d always wanted to paint myself, but I didn’t know how I wanted them to be. At the academy [of Fine Arts] in Vienna, they kind of directed me to what I wanted to say with my self portrait—and that became Detoxing Masculinity and Body Politics. From there, it was very clear that I wanted to paint myself and the people around me. So it’s more like documenting the lifestyles in my surroundings.

OB: To me, Body Politics is one of your most important series for this reason exactly, which is that it focuses on self portraiture as introspection. Given that we’ve all collectively experienced a pandemic and been socially isolated, how do you view the relationship between painting and isolation?

AB: I’ve been asked what the pandemic did for me: did it help my work in a way, or did it hurt me? I always say that it didn’t really affect anything for me, because I still went on to do the things that I wanted to do. The demand grew, but I still managed to go to the studio to paint because, like you said, to be able to paint you have to isolate yourself. There are other creatives who need to be out there to be able to gather that inspiration to paint, but I don’t have to be in a certain space. It doesn’t matter which situation I’m in, painting is something I will do no matter what happens.

Red Collar © Amoako Boafo, 2021. Courtesy of the artist and Roberts Projects Los Angeles, California.

Yellow Throw Pillow © Amoako Boafo, 2021. Courtesy of the artist and Roberts Projects Los Angeles, California.

OB: I think there’s a sense for many artists that when the work leaves the studio, it gains a life of its own, and you’re no longer in control of its interpretation, or how it’s seen. Certainly within a museum I experience that all the time. It’s the responsibility of the curator to speak to artists and to ask, ‘how do you want this work to be understood?’ As a curator, you can’t impose a particular reading or interpretation, but I’ve always believed strongly that you can create a critical context for that work.

When you’re viewing the work in a gallery, there is a commercial context that can limit one’s reading of a work outside of its aesthetic or financial value, but in an institutional context, you really want someone to have an intellectual exchange that is deeper than the immediate visual impression. It’s a different set of responsibilities. You’re an artist whose work has very quickly gained widespread attention all around the world, and it’s communicating to all of these communities. Are you happy for people to interpret the work however they wish?

AB: I wouldn’t want to create a wall around my work. I want it to be as free as possible. That’s the whole idea about it. When I’m making paintings, I want the characters to be strong, I want them to be free, I want them to be independent, I want them to be unapologetic.

OB: So many people connect your work to this idea of a kind of visibility and Blackness. You could say it’s a celebration of representation, which is not for its own sake, as there is a deeper interrogation of the self as spiritual presence. Lynette Yiadom-Boakye does that in a specific way, but through fictional individuals. There is something quite particular about you choosing individuals for your community.

AB: I admire people who just want to rely on memory and creating their own figures. I choose the characters from my surroundings because I feel like I have a responsibility. If I have the power to show people who are not always considered part of the community, and people who create spaces for others to coexist in, then I want to use my vehicle or voice to do that.

OB: When the Black Lives Matter movement gained momentum last summer, there was a lot of discussion around how institutions should respond. I think many institutions felt an external pressure to prove their allyship by exhibiting Blackness in one way or another, or by showing Black artists. What often gets lost is that the experience of Blackness is so plural and complicated, as you and I both know. It extends to my experience of Ghana’s diaspora—my grandfather arrived here in London in the 1960s— as much as it does yours being raised in Ghana.

Yet, we feel a kinship due to this idea of Blackness that has taken on a kind of universal message. One of the things that strikes me about your early work is this focus not so much on Blackness as a kind of definitive form of representation, but on the intersectionality of Blackness—through its relationship to queerness, to gender and difference. You’ve tried to ensure that the bodies represented in your paintings felt reflective of the world around you—that it wasn’t looking at any one particular gender expression. Is that something that’s been important to you?

AB: Yes, yes. I’ve always wanted to talk about that. Growing up in Ghana as a male, there’s a certain way you’re supposed to behave. We’ve all lived that way, and we’ve been okay with it—we just thought that’s the way to do it. Then at some point, if you are open enough, you see that’s not really the way one is supposed to live—you’re not supposed to be aggressive and ‘macho’ all the time to show you are male.

I have been thinking of ways to communicate that in my surroundings. It was quite difficult talking about it. When I arrived in Vienna, and found myself in a different situation, I thought ok, maybe this is the chance for me to dive into it. Maybe because I couldn’t find the right words to express it, people didn’t get it, but maybe with these paintings, I would be able to communicate what I wanted to say. The most important thing was to have people understand the idea behind those paintings.

OB: That takes us nicely into the role fashion plays in your work—and it’s something painters often have to speak about in one way or another, because unless you’re only painting nudes, at some point, you’re going to have to think about fashion. I’ve often seen that the opposition between art and fashion is that one is very serious and the other is frivolous. There’s this kind of false binary which has never really existed. You could go very far back in culture and see the collaboration between artists and fashion designers especially during the early European avant-gardes, Dadaists and Surrealists. When did you start to realise that the clothes, or self expression through garments, would be important in your painting?

AB: I’ve always used clothes to make a statement. What one wears helps to inform people of who they are, right? So clothes have always been part of me, and in my paintings—it’s one very vital element in my work. I might like someone’s visual expression, and that’s why I will paint them, but when it comes to clothing, it’s something I like to experiment with. Most of my characters don’t wear the clothes they were wearing when I took the picture. In the painting, I decide what they wear. It really translates the kind of energy and strength they possess. So it was only a matter of time before I would do a collaboration with a big fashion house, because that has always been there.

OB: Because of the curiosity and intellectual openness that it takes to work in an industry like fashion—where you’re drawing on film, art, design, everything at once—those references really have to be at your fingertips. I think that’s why people got so excited when they heard about your collaboration with Dior, because Kim Jones is not only a well respected figure, but he approaches fashion in an intellectual way. I want to ask you about that collaboration, because I think someone could look and say, ‘well, Amoako just put his work on a jumper and it sells in a store’, but a collaboration is never that simple.

AB: When I ask someone, ‘hey, I want to paint your portrait,’ and they’re like, ‘go for it.’ Or when someone asks me to do a commission and the only thing they will decide is the gender, and I have the freedom to do whatever I want to do, I mean, that kind of trust is amazing, right? Working with Kim [Jones] is like that. For him, collaboration is when you give someone the freedom to experiment and explore as much as they want. I knew there was going to be a surprise element in there, something which is like, ‘how did you even imagine this?’ Just working the images on clothes—and for clothes to look like a sculptural piece—is another experience for me, and a surprise to have witnessed.

OB: Many artists in the past have tried to suggest that clothes are not important, because what they’re trying to do is create a timeless image. With a lot of contemporary painters, by avoiding fashion, or avoiding any kind of reference to a brand name, the work can somehow exist outside of time. It could have been made in the ‘60s or the ‘20s, or now. So it’s interesting to me that you’re not afraid to depict your subjects in clothes that are very much of the moment. That’s a choice.

I think when people look at what’s happening now with the celebration and exposure of Black culture, there’s been a really positive shift towards not only fashion brands, but all aspects of consumer culture in taking Black audiences seriously. One of the decisions that distinguishes your work is the fact that you’re not trying to reach a ‘perfect’ image. There is imperfection in every painting, not only at a technical level, but also in terms of balancing shape and proportion. I almost feel that if your images were too constructed, they would lose their ability to communicate something deeply human.

AB: I guess that’s where we get to talk about my studies in Ghana and Vienna, and both have played an important role. Ghana gave me technical expertise—I was taught how to paint a bottle to look like a bottle, and that was good. I think it’s a foundation that every artist should have. But when I arrived in Vienna, I had freedom to experiment, I had to arrive at a painting of a bottle without going through that traditional process. I had different phases, and there was frustration. Because every experiment—I mean, you don’t get it right the first time. You have to make a few mistakes, and accept them and then work on them. But my goal was to always find a way to loosen up.

In Vienna, having access to all these museums, always having art in your face, looking at paintings—that helped me see new ways to make a painting without using traditional tools. I saw what I could create with the tissue if I imagined the tissue to be a brush. At first I thought my professor was a bit pushy. You don’t always understand what someone is trying to communicate with you, but if you take that criticism, and work on it, then maybe, just maybe, you can manage to loosen up.

OB: I completely agree. That’s when it really gets interesting. One thing that’s also struck me about your work is that it started to influence a new generation of Ghanaian painters who seem to be rising to the fore. I think traditionally, when artists feel there are others encroaching on their territory, or adopting a similar language, the immediate response is one of defensiveness. But what I see you doing is embracing that generation and becoming a kind of mentor.

AB: I think there’s a common element in what most Ghanaians are painting at the moment, which is figuration and portraiture. Maybe it’s because most of them have been a bit afraid to loosen up, and witnessing a fellow artist experimenting and moving away from the traditional way of painting helped them also realise they could let go and be free.

I do not really see it as a problem, because even if we might all say the same thing or want to do the same thing, we use a different language. Like you are in the creative industry, but you have one tool, and I have a different tool. We are trying to create awareness for Blackness, but we are seeing it differently. I believe most of them are creating and documenting their surroundings, in figuration and portraiture, and they have a different style. It’s just amazing. I’m happy that I’m able to open up spaces like that.

OB: The art market puts a lot of pressure on artists like yourself, where there is an increasing demand for your work that inevitably is out of your control. I know both of your galleries and I’ve known Mariane [Ibrahim] for a very long time. During COVID, there was such increased interest in your work. How did you shield yourself from something that’s so out of your control, and/or embrace it?

AB: I knew I needed a break, but I didn’t know how to get it, and the pandemic gave me that. I stayed in Ghana for a whole year without moving anywhere. I had enough time to reflect on things—what I wanted to do, and in which direction. When you keep running, there’s no time to sit and reflect. I started making plans and I could look out for things to avoid.

OB: As David Hammons said, ‘The way I see it, the Whitney Biennial and Documenta need me, but I don’t need them.’ In other words, curators and museums wouldn’t exist without artists. So often the power dynamics of the art world are such that artists feel like suppliers to this larger ecosystem, when in fact the artist is at the core of every one of these endeavours, whether it’s the gallery or the museum.

One of the things I’ve always believed—and it’s a controversial position to have working in the art world—is that the artist should always be reclaiming that power. Whether it’s having your own archive or ensuring that you keep early work, it’s fundamental. There’s a way in which the art world kind of manipulates young artists, so it’s something I strongly believe needs to be fought for, especially for African artists. We need artists supporting museums where government infrastructures aren’t willing to. We need established Western institutions engaging in productive dialogues with organisations on the continent, like the incredible residency programme you’re building in Ghana. Why do you think it’s important to set up this residency now?

AB: One, it’s important to give back to the community that inspired you to do what you do, get what you get, and who keep supporting and appreciating your work. Second, it’s important that there is a space made for creatives to grow in. The industry in Ghana is quite small, but there are a lot of talents there who don’t really know what’s happening.

In Vienna, you have all this support—artists know where they are heading. But in a place like Ghana, there are no grants so you can continue experimenting in your work. There are no museums that you look at, thinking, ‘OK, maybe one of my works will end up here one day.’ There’s this idea that if you travel abroad, you will make it, but that’s misleading. It’s not like ‘ABCD, I get a Visa, I go to Europe, and I’m gonna be an artist.’ So I feel if I have the chance to create space back home where people can have a sense of what is out there, then they could focus more on experimenting, and on painting.

OB: I’m working on a book coming out next year called African Art Now, which your work is featured in. It’s forced me to look at the differences between the ‘80s, the ‘90s, and the present. I think certainly in the 1980s, there was this expectation that in order for an artist to be successful, they had to go to a major European capital to build a career, and find patronage and support. And maybe eventually, later on in their careers, they would start either working on the continent, or building residencies programs and galleries.

But what’s happening now is this kind of homegrown movement, where artists from Ghana like yourself are coming back and not only having a dialogue within the local ecosystem, but transforming it. In terms of where larger Western institutions sit in relation to that, it’s incredibly important that they are attentive to what’s happening within those local ecosystems, and that we find a way to collaborate that is non-hierarchical and mutually beneficial.

AB: Yeah, I mean, I feel like the government could have done it. But if there’s something that I want and it’s not there, and I have the power to do it, then I will. I don’t want to talk about it, I want to show it, because maybe they don’t see—maybe they’re ignorant about it. So as much as I wish that the government would build new artists residencies, create funds and have national museums or national galleries, I feel like if individuals like us can take it upon ourselves to show it, maybe then they will come around and support.

OB: I think what you’re doing—being a champion for other artists and using your power to create a residency is incredibly productive. It hasn’t happened enough on the continent. I take my hat off to you, and I can’t wait to see what you do next.

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.