Earlier this year, Netflix released its gripping docuseries Cheer—an illuminating and at times distressing glimpse into the lives of Navarro College’s competitive cheer squad—two decades after Peyton Reed’s Bring It On won its way into our t[w]een-age hearts. Released exactly 20 years ago today, the cult classic not only capitalised on the American cultural fascination with cheerleaders, and launched lead actresses Kirsten Dunst and Gabrielle Union to certain fame, but its deeper message of appreciation and appropriation is one that seems only more profound with time.

First envisaged as a three-hour-long MTV documentary called Cheer Fever by screenwriter Jessica Bendinger, it was only after director Peyton Reed signed onto the project that it became a feature film with a straightforward but meaningful plot line. Dunst plays Torrance Shipman, the newly elected captain of the Rancho Carne Torros cheerleading team, who are chasing their sixth national championship trophy. When a new recruit, badass gymnast Missy (played by Eliza Dushku) joins the team, Torrance learns that their previous captain has been stealing their cheers from another squad: the East Compton Clovers—led by Gabrielle Union’s character, Isis. The Torros must scramble to find a new routine to beat the Clovers, who have every intention of attending nationals and earning the trophy they deserve.

Though disguised as a fluffy teen flick, Bring It On is actually a pressing commentary on race, class and privilege, and perfectly illustrates the harm done by cultural appropriation and colonialist practices. It quickly transpires that the robotic, white and affluent Torros have been robbing a predominantly Black team of its creative capital and labour, to their tremendous benefit.

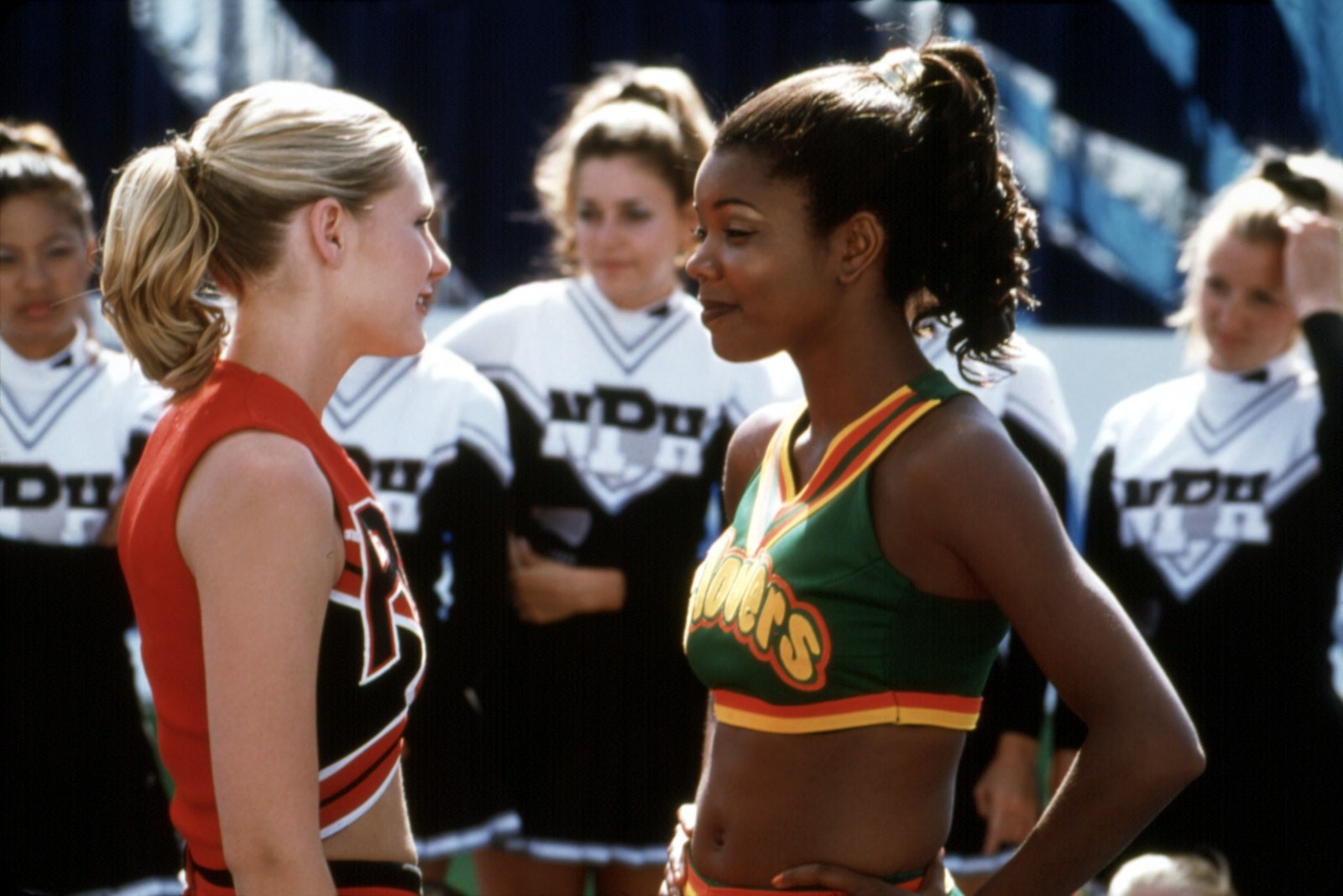

When a Clovers squad member confronts Torrance and Missy after a game, she asks: “Were the ethnic festivities to your liking today?” Union’s character, Isis, articulates centuries of injustice with candour: “Every time we get some, here y’all come trying to steal it, put some blonde hair on it and call it something different”.

Union explained her interest in the script’s vital and relevant message to Complex in 2015: “That is what appealed to me—the appropriation of our culture and winning awards and championships, using routines created and cultivated by black women who never got acknowledged, and couldn’t afford to get on that national stage to get recognised.”

It calls to mind the countless white performers who have been applauded for borrowing elements of culture that reinforce racist stereotypes in their originators, but when presented by privileged bodies, become fashionable, cool or edgy. The Torros whitewashed routines are evocative of the the hip thrusting phenomenon that was Elvis Presley, as well as more recent examples, like Miley Cyrus, Katy Perry, Taylor Swift—not to mention the prolonged car crash that was Iggy Azalea’s musical career. While appropriation is an age-old and regularly occurring phenomena in fashion, music, dance and art, our willingness to identify and discuss the epidemic is more recent—which makes placing this lesson at the heart of a high school Blockbuster in the year 2000 feel all the more radical.

The Clovers, who go on to earn a deserved championship title, are not the film’s antagonists, but rather its heroes, as the film continues to subvert cinematic cliches and challenges the audience’s expectations. Isis, who has every right to be pissed, does not conform to the racist “angry black woman” archetype, but rather remains calm and cool in her captainship—continually exhibiting far better leadership than Torrance, whose judgement is questionable at best.

Later in the film, when Torrance learns that the Clovers are struggling in their fundraising efforts to attend nationals, she hand delivers them a cheque. It’s a gesture reminiscent of the same “white saviour” phenomenon that’s been doing the rounds in the performative “wacktivism” of late. The Clovers, insulted by the assumption that an unwanted donation could right the Torros’ previous wrongs, refuse her charity and resolve to find their own way to nationals.

The genius of Bring It On is its ability to deliver meaningful societal critique in a film whose surface level merits are also undeniable. The fashion is a buffet of aughts gold—and many of the trends depicted in the film are still making mood boards today—but the teams’ uniforms cleverly reflect the central conflict: The Torros wear an Americana-esque red, black and white uniform, while the Clovers sport a green uniform with red, yellow and black accents, an allusion to various African flags. Missy’s character remains a beacon of 00’s (white) “alt girl style”, with her dark graphic tees, Alanis Morisette braids, and hip hugging cargo pants. Rehearsals are chock full of post- Sporty Spice looks that also feel pre health-goth: we see the best of Nike and Adidas paired with chokers and barrettes. The Clovers, off the court, embody the best of Aalyiah and TLC, are rock bold hair accessories, futuristic raver pants, and chunky shoes.

The cheers are also infectious (say “Brrrrr! It’s cold in here!” in the right tone at a party and you’re almost guaranteed an echo of “There must be some Clovers in the atmosphere!”) and the hardcore athleticism illustrates the challenge and legitimacy of a sport that’s often overlooked.

The soundtrack also speaks to the teams’ contrasting demographic. It oscillates between bubble-gum pop, like Atomic Kitten’s ‘See Ya’ and PYT’s ‘Anywhere USA,’ and R&B: multiple tracks are by the group Blaque, who are also cast as Clovers cheerleaders. At the regionals, the Torros bomb when performing to 2 Unlimited’s anthem ‘Get Ready For This,’, while the Clovers graze through hype montages of ‘Giddy Up Let’s Ride’ and 2 Live Crew’s ‘Shake a Lil Somethin.’ Two of the most memorable bits of Bring It On are the porny car wash montage, soundtracked by the Jungle Brother’s ‘Freakin You’ and of course the scene during the credits, which combines bloopers with a lip sync to B*Witched’s ‘Mickey’.

The script also nods to other issues in the sport, like its harsh beauty standards, which Cheer explored with grace and depth. The Torro’s pill-popping guest coach, Sparky Polastri, is an archetypal fat shamer. He delivers a slew of insults to the squad: “Too much makeup, too little make up, smile, don’t smile,” before demanding the entire team cut their daily calorie intake in half. On the way to a game, Jan (played by Nathan West), addresses the hyper sexualisation of female cheerleaders and the gay bashing that he and other men on the team endure throughout the film: “You’ll be fighting off major ooglers while we defend our sexuality!”

Of course, what’s most memorable about Bring It On will vary person to person. Whether it’s the excruciating meditation on sexual tension in the toothbrushing scene, the glittering displays of athletic prowess, or the pertinent point at the crux of the plot, there’s little question the film has affected the way we see cheerleaders, and more generally, each other. Even if you were just watching for the fashion, music or cheers—and the entire lesson of cultural appropriation went over your pigtails—it’s hard not to think that Bring It On has consciously or subconsciously, played a role in our generation’s willingness to confront the harsh realities of racial injustice. Bring It On’s 20th anniversary is one worth celebrating, because after all, how can you not wave your poms poms for a film that teaches you about cultural hegemony and spirit fingers in a matter of 100 minutes?