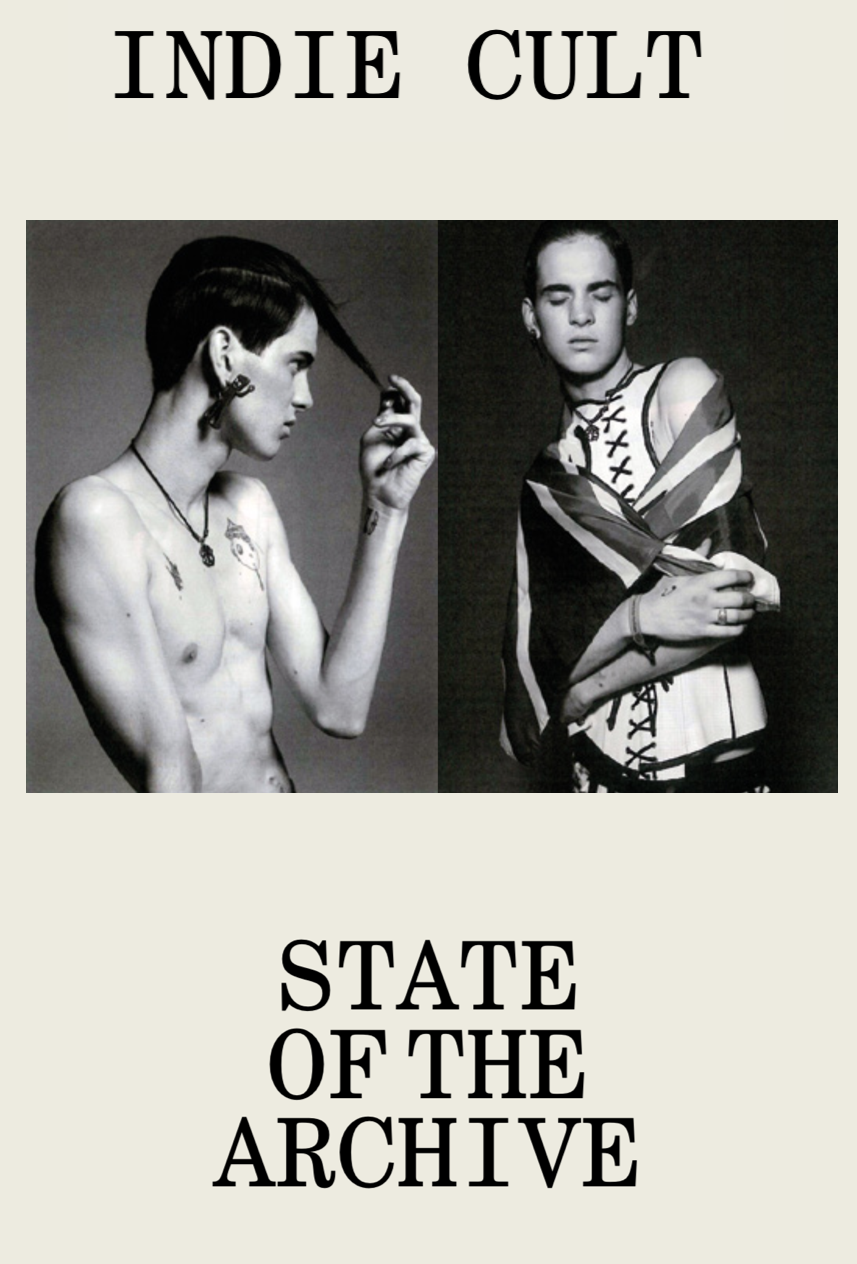

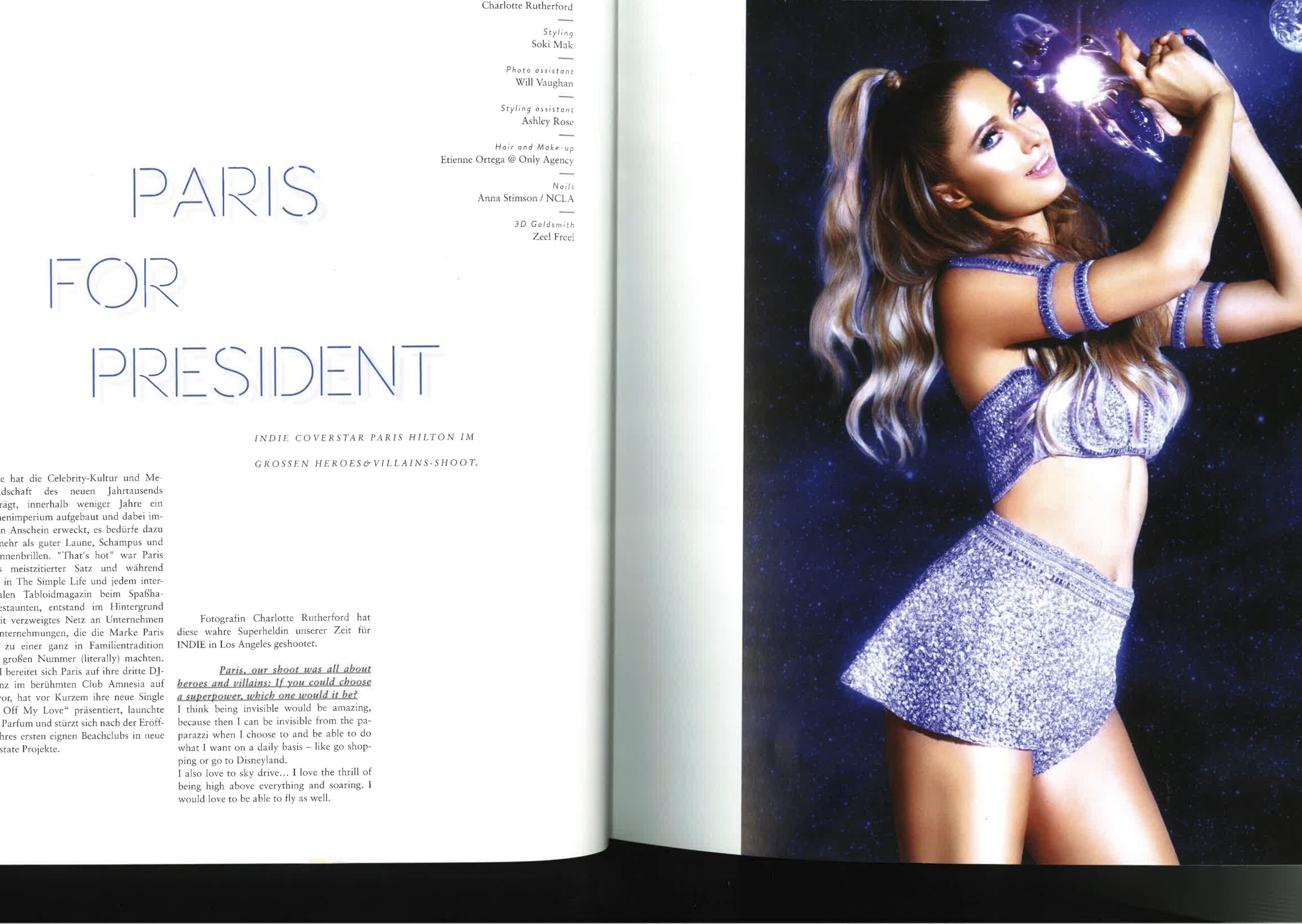

Throughout its 20 year evolution, the nucleus of the INDIE world has been its primary constant. Kira Stachowitsch founded the magazine at just 19, and has remained Editor-In-Chief ever since. Initially with no formal training and minimal funding to back it, the existence of INDIE twenty years later is near-miraculous—a bold statement of unflinching independence. Here, to mark the occasion, Kira revisits her favourite covers, shoots, and stories from issues of old—whether that be faces from the y2k indie music universe such as Peter Doherty, or international celebrities such as Jared Leto—to form a patchwork, or subcultural collage, of wildly diverse faces, scenes, and aesthetics.

Though it wasn’t always the case, today, much of INDIE looks like a high fashion magazine. Upon establishment in 2003, the focus of the magazine was placed firmly on music and alternative style. Yet over the years, the INDIE lens has expanded to incorporate high fashion into its wider cultural outlook, in part thanks to the rapidly evolving fashion landscape of today. William Ndatira (perhaps better known as @williamcult on Instagram) has seen it change first-hand. An editor, art director and long-time friend of INDIE, Ndatira has worked with the biggest brands and publications in the fashion world. He arrived on the London scene from Switzerland, where he was raised, at a time when styles and designers we take for granted today were still avant-garde. Subculture was influencing luxury like never before; figures like Hedi Slimane were pushing a new agenda which suddenly seemed compatible with INDIE’s vision. Chatting with Stachowitsch, Ndatira recalls the people, the parties, and the tricks of the trade on the fashion circuits of the 2000s and 2010s. In dialogue with each other and with archival shoots, the two reflect on fashion’s changing relationship with counter culture, and where INDIE got involved.

Irina Lazareanu by Edouard Plongeon and Marine Braunschvig, Issue 34, 2012

WILLY NDATIRA: I moved to London around the time when Pop magazine launched—when all these big styles that now define the luxury landscape were still the independent, up-and-coming generation of the time. Their approach, based on the music scene and subculture, connected the underground with fashion.

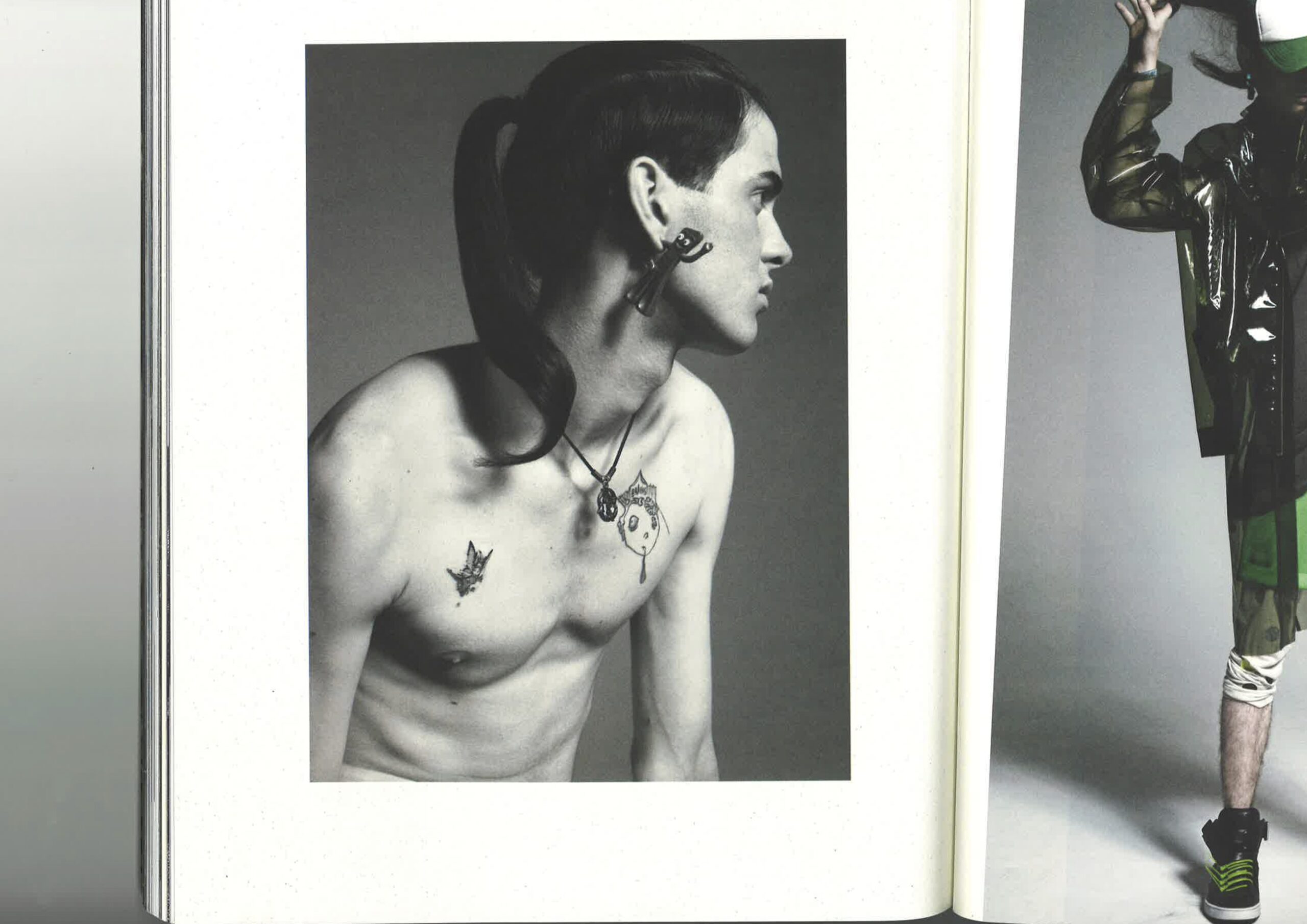

Jethro Cave by Stefan Heinrichs and Ylmaz Aktepe, Issue 24, 2009

WILLY NDATIRA: It was interesting to see all the early graduates arriving on the scene. At this point Stella McCartney had just done her graduate show, and Alexander McQueen was still alive. You could see all these characters on the streets of Soho. Styles emerged through people: they’d be seen in a club in London and would trickle down into the pages of The Face or i-D, and then it would influence how people dressed worldwide. So it was through this kind of organic curation that subcultures were shaped.

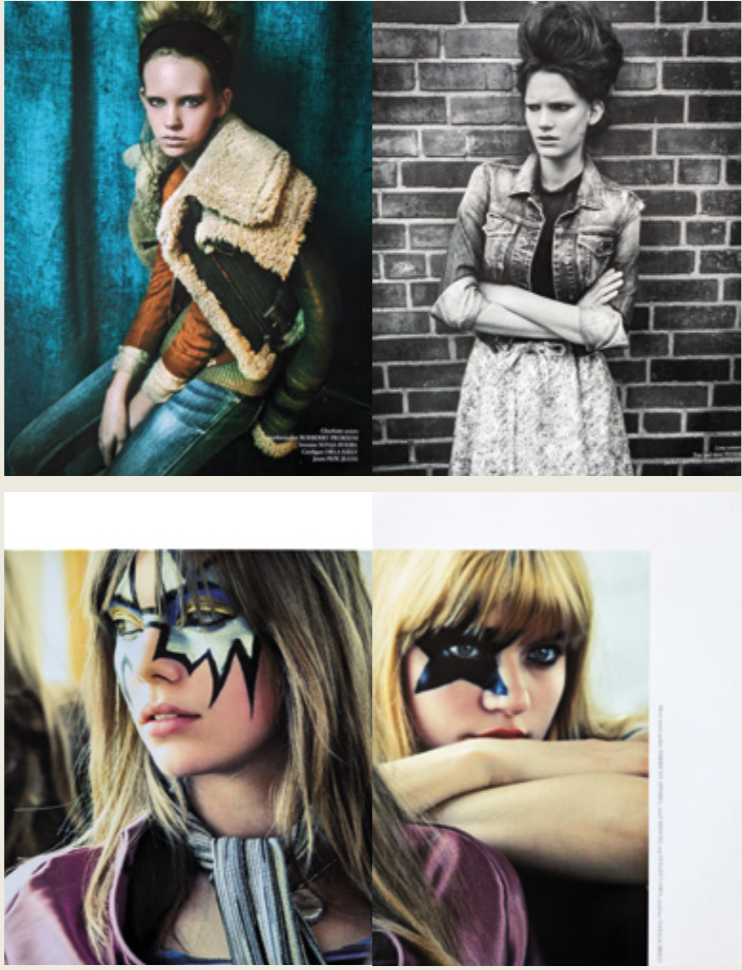

‘Rollin’ over’ by Armin Morbach and Ingo Nahrwold, Issue 29, 2010

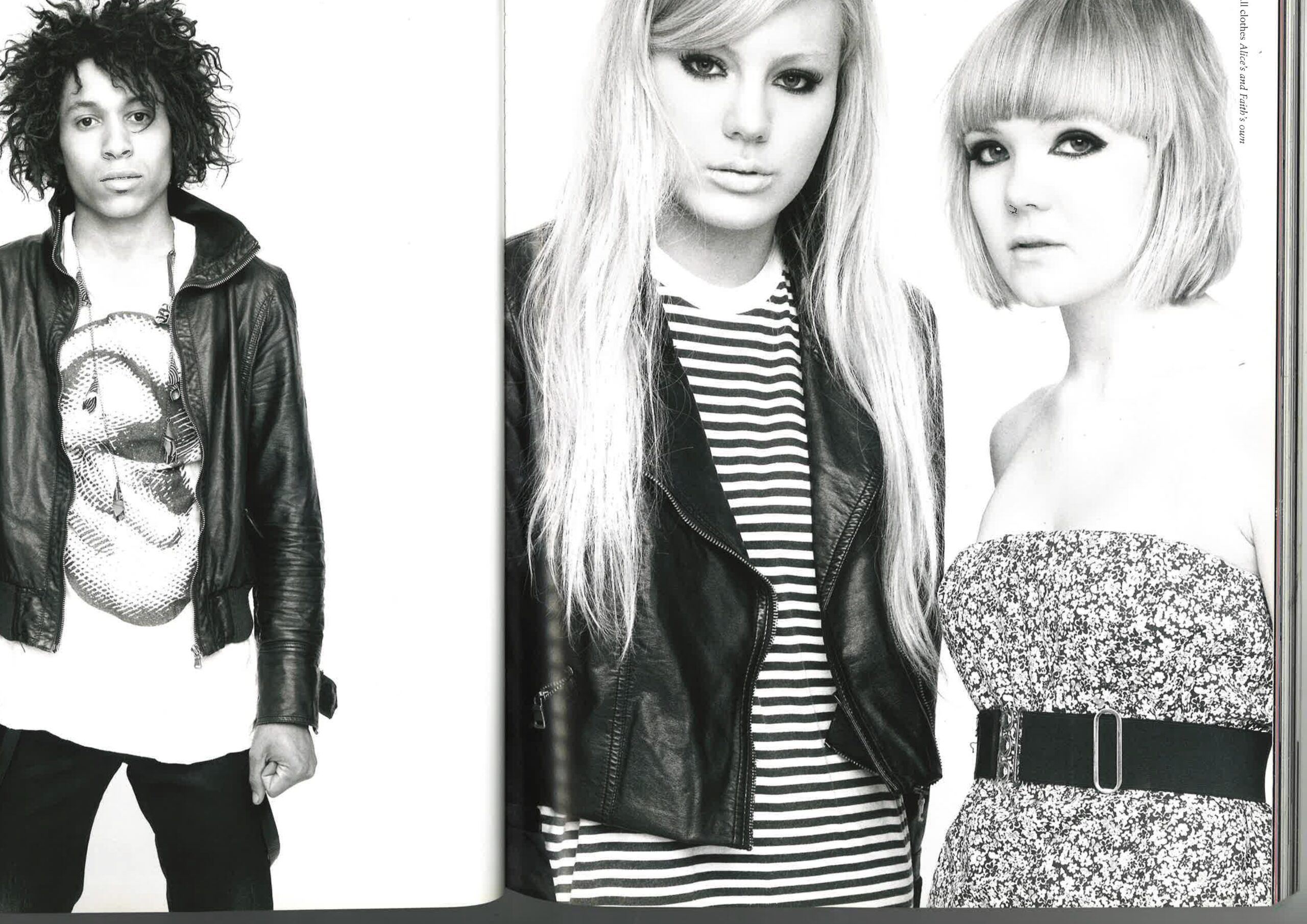

‘Baby Driver’ by Raphael Just & Pigeon Disco, Issue 23, 2009

WILLY NDATIRA: This era was about saying, ‘Just because something is distressed, or unfinished, or the environment isn’t beautiful, it doesn’t mean that something beautiful can’t be created from it.’ It was an attraction to the things that are overlooked, that have traditionally been be considered “ugly”. It’s about establishing some kind of identity outside the boundaries of good taste.

Natalia Vodianova by Elfie Semotan, NYC, 2003

(Inspired by ‘Bad Seed’ and John Walters), Courtesy Studio Semotan

WILLY NDATIRA: I was hired just based on how I dressed and how I looked. It was just like, ‘You’re a cool kid. Why don’t you come and work here?’

KIRA STACHOWITSCH: I remember—and I guess I must have been 20 at the time—that this Hedi Slimane, Dior Homme era had such a big impact on us when making the magazine. It was eye-opening, and perhaps also a transition from the world of music into fashion. We suddenly felt like this scene was also for us.

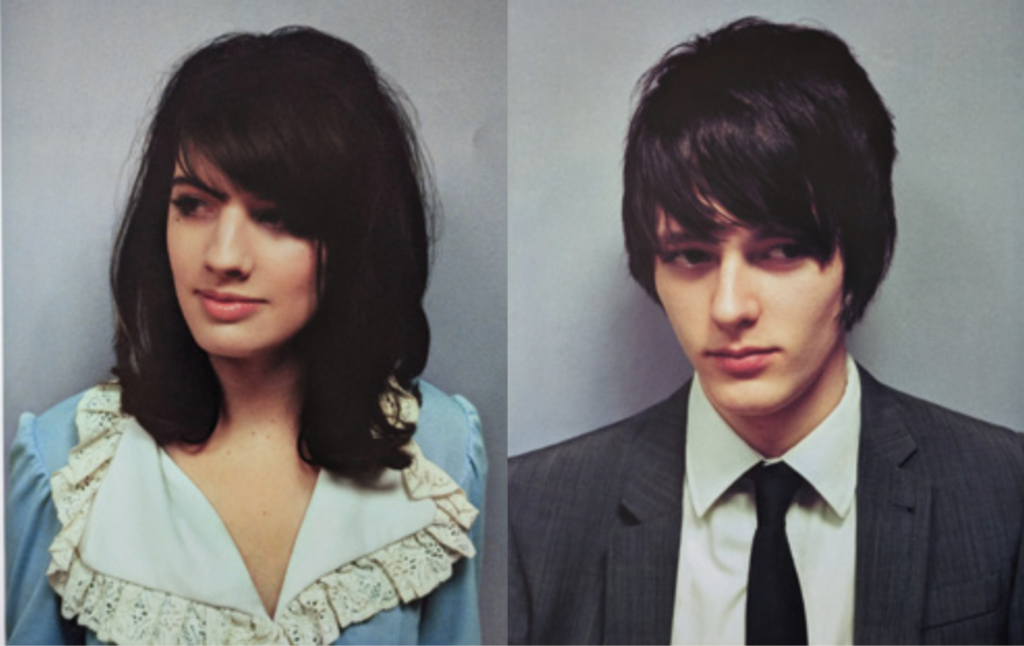

‘Modernists’ by Mark Kean, Issue 32, 2011

WILLY NDATIRA: Before, luxury brands were very conservative. They were things you bought and kept for ten years because they acted like class markers. Then these guys came in and everything changed. They were making garments that you would normally see on an indie kid in a club, but now it had ‘Dior’ on it. It was refreshing. I was obsessed with Galliano and Westwood. But Gaultier also was very important for me growing up.

WILLY NDATIRA: I remember flipping through my sister’s Vogue growing up, and it was all women in Chanel with big gold earrings, and Inès de la Fressange… When I discovered Comme des Garçons, I was shocked. I realised how much was possible in fashion—using imagery in a different way, turning fashion on its head. Now, everybody takes that for granted—everybody does sneakers, for example. But at the time, it was unheard of. A pair of sneakers from Hermès? No way!

‘We Are All Made of Stars’ by Mark Sanders & Harris Elliot, Issue 19, 2008

KIRA STACHOWITSCH: Yeah, absolutely. It’s easy to forget how exciting that was, but it was so new. I mean, the concept of counterculture playing into fashion—that’s an old one. But it was the luxury segment changing that was important.

KIRA STACHOWITSCH: Since people couldn’t make their own stardom on social media, it became the role of the tabloids to create these people, so that they would have someone to exploit, basically. People like Alexa Chung, for example, who were a part of that it-girl culture in the 2000s… a lot of these people were constructed to feed the industry.

WILLY NDATIRA: Also, I think it was the start of voyeurism. Social media wouldn’t have worked if we didn’t have a tabloid culture before that was so obsessed with what these celebrities were up to. Even I happened to buy tabloids and see grainy pictures of Madonna on a Greek island or something. And then you had the Kardashians. But I think social media would feel a lot more creepy if we weren’t already desensitised by tabloids, and always wanting more information.