The team behind independent fashion bible 1 Granary explore what the concept of independence means in the fashion industry today—a place where freedom and creativity flirt but never marry.

When Freddy Coomes picks up the phone, his excitement is palpable, even through a lagging WhatsApp connection. With his eyes gleaming and his speech high-paced, the print design student explains he’s working on a special project, and that Central Saint Martins, the university where he’ll start his final year BA in September, offered him a studio to finalise it. “We have so much space, we can place one look on each table—it’s amazing!”

Just like the metres of fabric he collected for the project, Coomes’ enthusiasm is spilling over in all directions. The student is nearing the archetype of the fashion designer on all fronts: bursting with energy, free, and independent from restrictions.

In reality, however, this luxury is incredibly rare—in this case only possible within a very specific pedagogical context. Fashion is a notoriously competitive industry. A recent study by research platform Prospects found that only half of UK fashion graduates go on to get a career in fashion and only one in seven fashion design students find employment as designers, with the rest taking on roles in retail, marketing, sales and administration.

The minority of graduates that do find an in-house design position soon learn that creative brainstorming only makes up a tiny part of their jobs, which mostly consist of administrative office work. “A lot of students are disillusioned as soon as they work for a big house,” says Daniel Olatunji, who worked for Urban Outfitters before setting up his own label, Monad London, in 2016. “Working in a big luxury house or working for a high street brand, it’s not as creative as you imagine it.”

Those who crave full creative freedom often choose to set up their own label. But here too, independence and creativity are inevitably tethered to practical and financial realities—to unpaid invoices and studio rent, to pushy retailers and rude PR requests.

The fashion industry is not only competitive, it’s also incredibly unfair—inaccessible to those who don’t live in a major metropole, or whose parents can afford to support them through years of unpaid internships. Social enterprise Creative Access found that 85% of creative roles are recruited via word-of-mouth over advertised positions, which means it is practically impossible to land a gig in fashion unless you know someone on the inside (read: nepotism).

The investment it takes to set up your own brand is also incredibly high, and doing so without the financial backing of an investor or family means you need a lot of patience and hard work. “It’s so expensive,” shares Michael Stewart, who independently launched his brand Standing Ground after graduating from the Royal College of Art in 2017 but worked full-time for a high-street brand until he was selected for Fashion East in 2022. “There’s so many people entering the industry, everyone gets drowned out by those who can afford to do it.”

Still, London is ripe with creative mavericks who decide to go their own way. Why do they choose independence—and what does it look like?

Image courtesy of Freddy Coomes and Matt Empringham

A mindset.

Choosing independence means choosing a life dedicated to creativity, and sacrificing security or stability in its name. “The reason I started my brand was the need for self-expression, that was the primary goal. I didn’t get too much into the business side at the very beginning. But then reality hit me hard and quick,” shares Azerbaijani designer Fidan Novruzova. Even a legendary name like Lee Alexander McQueen never forgot the sacrifices he made in order to achieve success, and what it meant to him. In a famous interview with Suzannah Frankel for AnOther magazine, the iconic designer said, “Having money hasn’t changed me. If anything, it’s made my life worse. I’m prepared to forget about money if it affects my creativity because, remember, I started off with nothing. And I can do that again.”

To the designers who decided to start their own label after graduation, independence was never even a question. When they speak about the origins of their brands, they routinely frame working for themselves as the only viable option. Take John Alexander Skelton for instance, whose sophisticated and artisanal menswear collection gained him a cult following in cities around the world. To the Yorkshire-born designer, independence has always been intrinsic to his working method. “It’s part of my personality to be able to have control,” he explains. “I feel very uncomfortable when I don’t. Independence for me was the only way forward.”

The same goes for Kathryn Hewitson, founder of Pristine. Her sexy and provocative womenswear might be light-years away from Skelton’’s aesthetic, but the thinking behind her decision-making is exactly the same. “It’s something that never really felt like a choice. I’ve never understood why you wouldn’t take this route.”

Though London is still considered the epicenter of independent talent, it’s not easy to grow beyond a niche cult status without outside support—whatever form that may take. Amongst the legends, John Galliano had the financial backing of venture firm Arbela Inc. and Alexander McQueen famously sold 51% of his company to Gucci in 2000, seven years after his first runway show. Even indie queen Vivienne Westwood had a franchise relationship with the Manchester-based Hervia, who operated stores for her brand.

Independence is a mindset, a way of expressing and organising creativity. That doesn’t mean creativity in and of itself. “I think that people who work for others are incredibly talented,” says Skelton. “You need an incredible range of cultural capital to be able to put your own vision aside and design with a wider variety. People don’t think about these profiles enough.”

Working for someone else might come with a tighter framework, but to some, those limits stimulate their creativity rather than suffocate it. To Coomes, interning for other brands (most recently an undisclosed LVMH-owned luxury label) allowed him to generate ideas at a much higher pace. “I adored the scale, the energy, and the speed,” the student shares. “You can be a lot faster with different ideas and projects. They’re very good at actualizing ideas, so you never feel stuck.” In this corporate structure, Coomes found the practical support he needed to focus on his work. When his laptop broke, the company immediately fixed it. “If I hadn’t been working, I would’ve had to do that myself. It takes a lot of energy, any minute you’re thinking about that, you’re not thinking about what you want to make.”

Image courtesy of Fidan Novruzova

A risk.

Still, independence remains a much sought-after status among creatives. In fashion, however, it’s particularly difficult to achieve. Working as a clothing designer, you’re inevitably dependent on resources and collaborators to actualise your ideas. Contrary to, say, a writer or a painter, who can create work in relative isolation and with rather minimal resources, producing a collection requires heavy investments. If you want to work independently, you have to make those yourself. “It comes with a lot of baggage if you want to be truly independent,” Skelton admits. “It’s very hard.”

“You have to be relentless about not giving up, which isn’t easy because it’s so expensive to do things,” Stewart explains. “There are so many sacrifices you have to make in order to hold on. I’m 34, so a lot of my friends are buying houses. I’m nowhere near doing that. Every penny I had went into the brand, buying equipment and paying collaborators. You put yourself in a precarious financial situation.”

In creative industries, independence and freedom are used synonymously, as the cultural imagination tends to glorify the lone, free-thinking artist and eschew anything resembling the 9-to-5 grind. “But the word freedom does not describe my situation,” shares Hewitson. “I love my work, but realistically I have been working 12-hour days, six days a week, for a year and a half now.”

The high investment cost of fashion production forces designers to confront their financial realities early on and ask themselves: ‘Can I afford my creative independence?’ Being independent in fashion means constantly negotiating commercial and artistic intent.

“I didn’t have any money behind me,” Hewitson says of launching Pristine. “I have shitty personal credit, so I needed to find a way to make it my main source of income, not just a vanity project.” Through trial and error, the London-based designer learned to find the right balance between art and commerce, with a few surprises along the way. “At the start, I would make some things because I thought they would be popular and sell well, but often, it’s the weirder stuff that works. I guess people don’t want basics from a smaller brand.”

Image STANDING GROUND

A drive.

But financial hardship doesn’t necessarily imply a loss of creativity. While many designers sacrifice their free time and financial security in order to set up a label and work independently, this only further stimulates their curiosity and sense of innovation. Such is Olatunji’s experience. “My financial restraints always forced me to think creatively, because you can’t just outsource everything,” he explains. “When I have to do a lot of things myself, it helps me understand the design and making of a product better, which you don’t get when you’re working in a house, where you send your design to a garment tech.”

The London-based designer describes a work and production method that is entirely his own. Because Olatunji cannot rely on a larger institution to take care of production, his creativity is put to work in setting up his own network of collaborators and artisans. He ventures off the trodden path, which inevitably means he needs to invent his own systems and processes.

Independent designers learn to find satisfaction in business. “There were times when growing the business felt like a bigger milestone than my creative growth,” says Fidan. “It’s experience that felt extra rewarding, because I had zero training in it. It really felt like – I did that!”

Being independent also requires a lot of communication. It’s one thing to have a vision, but being able to explain it to others, with concrete execution in mind, is something else entirely. Skelton recounts diving into an unofficial network of hobbyist and amateur knitters to find someone who could produce a patchwork design. It took three knit disasters before he found the right person to help him. “I’m doing something the hard way because it’s worth it. I like hand knitting more than machine knitting. It’s worth it, exactly because it’s harder.”

Being independent means being an innovator—not only when it comes to designing garments, but also where business models and sustainable practices are concerned. “Independence doesn’t just give me control over my designs,” explains Tabitha Ringwood, an independent shoe designer based in London. “It also gives me control over sourcing and manufacturing, and allows me to be as sustainable as I can within all aspects of my business. I am the decision maker.” The RCA graduate worked for multiple high street brands before launching her own business, and the lack of freedom she experienced in those roles is exactly what pushed her to start under her own name. “Fundamentally, independence allows for me to gain a sense of fulfilment and satisfaction that is unmatched in the areas of the industry in which I have worked.”

For every independent fashion label in London, there is a unique business structure and approach, and designers learn early on that a one-size-fits-all approach can’t be applied to the way they run their company. Monad London, for example, works with a lot of artisans, so Olatunji cannot afford to work on consignment with retailers, his collaborators needing to be paid faster than a conventional factory would. He also can’t produce the same quantities as a mass-produced line. “Stores will ask for twenty pieces, I’ll say I can give five.”

Skelton is equally selective when it comes to the retailers he works with, prioritising those who understand and appreciate his alternative approach. “I don’t just sell to anyone. I couldn’t fathom doing massive orders for big retailers. It would be detrimental to what I do. Too often, young designers are so eager to get a retailer, but they don’t think about whether that retailer is able to sell them.”

Image courtesy of Freddy Coomes and Matt Empringham

A spanner in the works.

There is one element to the system, however, that is impossible to escape as an independent designer: the dreaded fashion calendar. “If you want to sell in certain shops, you have to adhere to their schedule,” explains Skelton. “It’s a sort of necessary evil. In an ideal world, I would finish my collection whenever I wanted, but at least it also gives me a structure to work towards.”

“The calendar is a constant source of conflict,” agrees Hewitson, who never wanted to work with wholesale, until she was contacted by Ssense. The high-end online store was a marketing opportunity she couldn’t resist and she has been producing her pin-up-inspired corsets and silk lingerie slips seasonally ever since. Though it’s great to have her name out there, it can also feel like “being stuck in a hamster wheel”, always catching up to the next deadline. Techniques that take longer to develop, like embroidery, need to take a back seat. There is a definite power dynamic between independent designers and the retailers they rely on to get their clothes to a client, one that cannot be ignored.

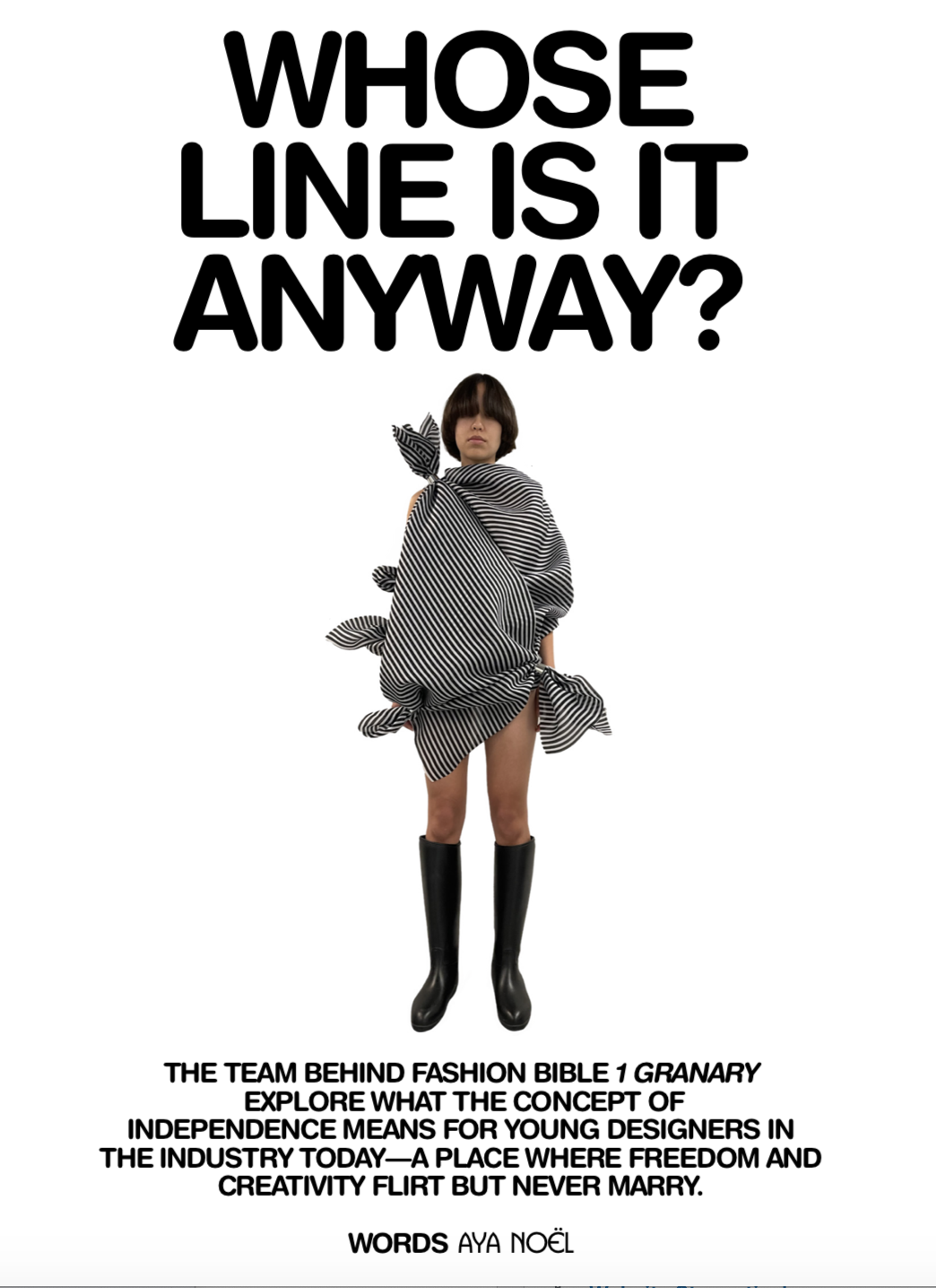

And therein lies the catch. No matter how independently you may want to work, participating in the fashion system enforces a particular rhythm, and by extension work process, on creatives. “The way I think isn’t very viable for the fashion model,” says Eden Tan. The menswear designer recently graduated from Central Saint Martins, winning the L’Oréal Professional Young Talent Award for his conceptual collection, in which each look was crafted from a roll of fabric. Considering the rigidity of the fashion system, will it be possible for Eden to monetise this unique creative process?

“I like to do a lot of primary research, working hands-on with material, and that takes a long time to come up with. With the fashion cycle, that can make things quite difficult. Big brands are not very adaptable, but our working methods will have to change, especially if we want to respond to the climate crisis.”

As the fashion system grows at an ever-increasing pace towards uniformity and marketing-driven sales strategies, leaving little space for creativity and out-of-the-box thinking, there is hope to be found in the grassroots thinking of these independent designers. They stubbornly do things their own way, charting their course as they go along, and throwing spanners in the functioning of big, established corporations while they’re at it.

“It’s 100% mountain goat mentality. They’re insane. The ledges they’ll climb just to get to a little tuft of grass. Why can’t you just walk down the hill?” Olatunji laughs as he explains his view on independence, explaining his mentality in the same breath. “I might be happier financially, but I would be miserable elsewhere.”

Skelton wholeheartedly agrees. When asked about the meaning of independence, he only needs one word. “Happiness, I suppose. I can’t define it further than that. Without it, I would be unhappy, and I wouldn’t want to work.”