As conspiracy merges into the mainstream and fringe beliefs are fed to us by algorithm—when it comes to radicalisation, have we passed the point of prevention?

On 24 August 2021, yoga influencer Stephanie Birch posted a photo of herself with windswept hair, a laidback smile and eyes half-squinting into the camera to her 50 thousand Instagram followers. The caption began: “I’ve been asked if this account has been hacked, it hasn’t.”

Birch—whose feed was until then comprised of inspirational quotes and yoga poses—was one of many Instagram influencers whose content went from cute and wellness-adjacent to conspiratorial over the pandemic. In a now deleted post of a blue sky with the caption #greatawakening, she roused QAnon sentiment by using a hashtag associated with the conspiracy claiming Satanic ritual abuse of children by a secret cabal of elites.

Behind coded hashtags all over the internet, extremist ideologies are hiding in plain sight. The “trend” has become so prolific that disinformation experts have dubbed it ‘PastelQAnon’—the act of concealing harmful content behind classic Instagram aesthetics. They argue that influencers have not only normalised conspiracy theories to followers who trust them deeply, but have made fringe ideologies look aspirational.

Conspiracy has plagued the wellness space since well before the pandemic. In 2011, academics Charlotte Ward and David Voas coined the term ‘conspirituality’ to describe the overlap between the two spheres, suggesting that an interest in spirituality and wellness often resulted in a distrust of institutions and support of alternative medicine. But as the world entered into lockdown and social media became the preferred medium of information, the dissemination of disinformation and dangerous fringe beliefs by influencers spread like wildfire.

In 2020, actor Woody Harrelson shared a report on his Instagram claiming that “5G radiation” was “exacerbating” Covid. Three months later Madonna insisted that governments were withholding a Covid jab from the general public, alleging “they would rather let fear control the people and let the rich get richer and the poor get poorer.”

As more and more people re-shared such posts, the rhetoric within them began to trend, and was consequently fed to unsuspecting users by algorithm. It’s a process that begins online but has proven to have real-life consequences. “Covid changed quite a bit,” explains Amarnath Amarasingam, senior Fellow with the International Centre for the Study of Radicalisation. “It led to a broader collapse of trust around public health officials, media, journalists, academics, researchers, and government officials, which mainstreamed a collapse in societal trust overall.”

During the course of the past year, we witnessed a mass of horrifying events highlighting the real-world dangers of radicalisation. In May, a gunman in Buffalo, US, opened fire on Black victims—an attack which was later linked to white supremacy. That same month, a shooting in Oslo was labelled an “act of Islamist terrorism” by the police, when a man attacked a popular queer club in Norway’s capital city.

“Algorithms play a key part in spreading disinformation, and are really strong at driving people down these radicalisation rabbit holes,” says Simon Purdue, Director of the Domestic Terrorism Threat Monitor at MEMRI (The Middle Eastern Media Research Institute). Disinformation is often the stepping stone to radicalisation, as people begin to question mainstream narratives. And while the actual amount of extremist content online has reduced over the past few years—partly due to social media entities de-platforming key figures, such as far-right conspiracy theorist Alex Jones—Purdue believes algorithms have become more dangerous. “If you kind of think of an algorithm like a magnetic force, that force is stronger than ever before and working quicker.” Users don’t even need to watch videos to the end—simply hovering over a post longer than usual will cause the algorithm to regurgitate more of the same content.

In May of this year, the internet exploded in brazen misogynistic misinformation targeted towards Amber Heard during a defamation case with her ex-partner Johnny Depp. In an opinion piece, she had stated she was “a public figure representing domestic abuse,” and while she didn’t identify Depp as the perpetrator of this abuse, he took her to court. Twitter hashtags branding Heard a psychopath or a turd went viral daily during the five-week trial, and people reported seeing countless anti-Heard Instagram posts despite never searching for anything related. Clips of Heard’s testimony alongside unfounded claims she snorted cocaine in court were re-shared numerous times on TikTok. During the trial, a VICE World News and the Citizens investigation discovered that conservative media outlet the Daily Wire, founded by Ben Shapiro, had spent tens of thousands of dollars promoting misleading news about the trial on Facebook and Instagram.

People were being shovelled one-sided coverage of the case by a conservative outlet that rigged Instagram’s algorithm through paid promotion. It’s just one example of the kind of manipulation and distortion that’s possible through online propaganda. Heard’s annihilation via social media gave mainstream validation to a kind of targeted misogyny we haven’t seen in a post-#MeToo era, opening a gateway for such beliefs to resurface online again.

While disinformation is an entry point to extreme views, it isn’t the reason people hold onto them. Professor Amarasingam says it is the community relationships that arise from disinformation that makes people stay—as opposed to the beliefs themselves. “As certain ideas fluctuate and disappear, those communities are still maintaining themselves,” he explains. “A good example is the 5G theories that started March 2020 onwards and have become less popular. But in those communities, they’ve just replaced that with Ivermectin [an antiparasitic drug falsely hailed as a Covid miracle cure in conspiracy circles], or something else.” People are galvanised by the idea that they can see the truth, and have a mission to wake everyone else up.

YouTuber Caleb Cain, known as Faraday Speaks on his channel, was sucked into the far-right in 2013. A 21-year-old student at the time, he had dropped out of college due to spiralling mental health, and was sucked into a YouTube vortex of extremist beliefs. The New York Times’ podcast Rabbit Hole explored his near-miraculous deradicalisation, partly by the same algorithms that radicalised him in the first place.

Cain explains that the initial draw of the far-right community came from the validation he felt watching Stefan Molyneux—an Irish-born Canadian far-right white nationalist, men’s rights activist and white supremacist now banned on YouTube. “He had a similar rough upbringing. And so I related to him a lot. He confirmed society is screwed up, it doesn’t care about you. And it’s because society is run by a bunch of idiots, who aren’t going to fix the problem. And I was like, yeah, you’re right.”

Like Cain, many of the people drawn into conspiracy theories and radicalisation feel alienated from mainstream society, which is why community is so vital. When comedian Dave Chapelle takes aim at transgender people, it validates and incentivises people secretly harbouring these views to share them and find others who feel the same. When broadcaster Piers Morgan publicly bullies Meghan Markle, it sends a direct message to racists that their views are legitimate and acceptable to communicate in public. When podcaster Joe Rogan revels in misogyny and sexism, the same process happens. In recent years, there has been a wider cultural shift to view radicalisation through extreme and harmful ideology such as transphobia, anti-abortion, anti-vaccine and misogyny. “Radicalisation isn’t just about a political worldview or political opinions,” Purdue affirms. “It’s an entire worldview, and when people are radicalising, it’s not like they’re picking one thing to focus on, it’s the full sweep.” It is the grouping of these beliefs that leads to distinct realities between those radicalised and those not.

But while culture has adapted its definition of radicalisation, establishments tasked with deradicalisation have not. At present, the majority of prevention programmes are focused on stopping violence. “That’s kind of where we’re stuck,” says Professor Amarasingam. “It’s not illegal to believe wrong information and it’s not illegal to be an asshole, so it does create these problems for intervention.”

“If you’re a supporter of ISIS, or a supporter of some far-right group, like the neo-Nazi terrorist group Atomwaffen Division, and you’re plotting an attack somewhere, that’s a bit clearer that some sort of intervention needs to happen. Whereas if I say ‘I believe that Biden is a paedophile’ it’s not entirely obvious, and who would be responsible for tackling something like that?” Most intervention providers he knows of haven’t taken these forms of radicalisation on as an issue that needs to be addressed, because it hasn’t tipped over into violence and is not identifiably societally harmful.

This may ensure funding is most effectively used to protect society, but it clearly has its limitations. Falling into a rabbit hole of pro-Kremlin TikToks pushed onto the platform during the early days of the Ukraine invasion might not lead a user to buy a gun and attack anyone, but this content is undeniably dangerous. Consuming content which invalidates Ukrainians’ lived experiences from the comfort of a bedroom miles away, can be a gateway into other forms of disinformation and extreme thought.

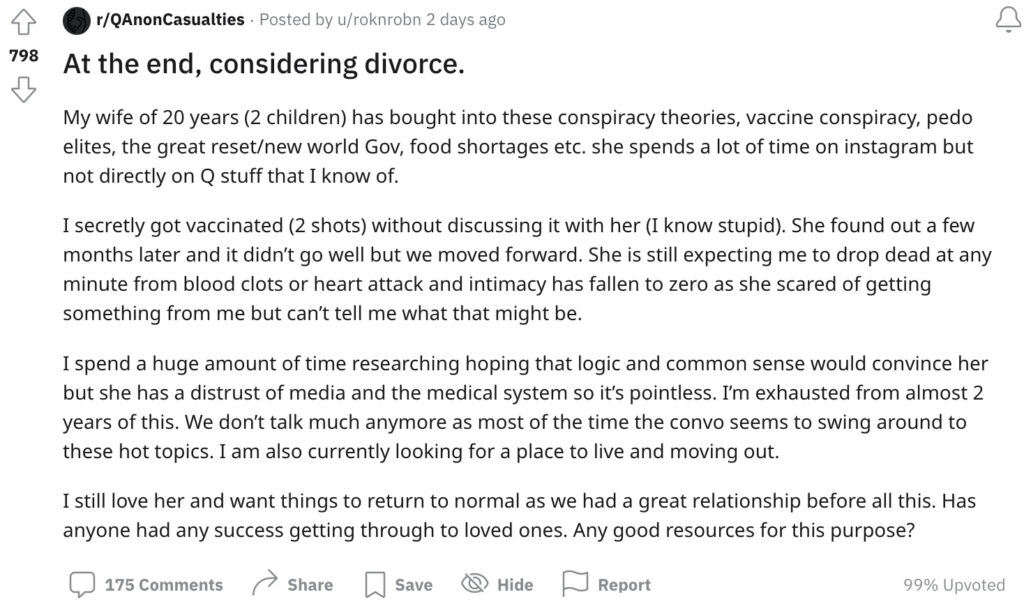

“I’m in touch with a lot of social work groups who get calls from children saying: ‘My mom’s gone down the YouTube rabbit hole, what do I do?’ And they’re just like, well, we have social work here, and you’re not necessarily the top five of our concerns,” Amarasingam says. In response, online communities have begun to crop up to offer solace and advice. Reddit’s ‘QAnon Casualties’ is a support forum with 240,000 members for victims of radicalisation and their families. Such forums are helpful, but few and far between, and are often set up by everyday individuals lacking professional expertise.

Louise Tiesson, co-founder of the thinktank Deradicalization and Security Initiative, often looks to history for lessons on how to help those drawn into extremist ideology. “After World War Two,” she explains, “members of the Hitler Youth went to dance classes, met people of the opposite gender, and it repaired the cognitive closure that took place during radicalisation.” The same approach has been adopted in French prisons to de-radicalise those involved in Islamic State terrorism—by fostering a different sense of community and belonging, and offering expanded counselling.

Conspiracy theories and extremism were once associated with the dark corners of the internet. What’s becoming increasingly dangerous now is that disinformation, and the pathways to radicalisation, are so engrained in our everyday lives that they’ve become almost invisible. We see them on our TikTok ‘For You’ pages, via online hashtags and Instagram Explore, and social media giants are playing a cat-and-mouse game to understand what the algorithm feeds us. While figures like Alex Jones and far-right figure Tommy Robinson have been deplatformed, micro-influencer Stephanie Birch continues to share her photos on Instagram. There are no ‘Pastel’ hashtags on her profile anymore—no trace that she effectively urged her followers to follow QAnon in 2021. With gateways into conspiracy communities becoming more impalpable than ever, it’s no longer enough to confront the holes in our society when they culminate in violence. We must reckon with the record levels of loneliness, and widespread alienation that’s plaguing the next generation. As Professor Amarasingam affirms, prevention is stuck in reality, while action has long shifted to the digital world.