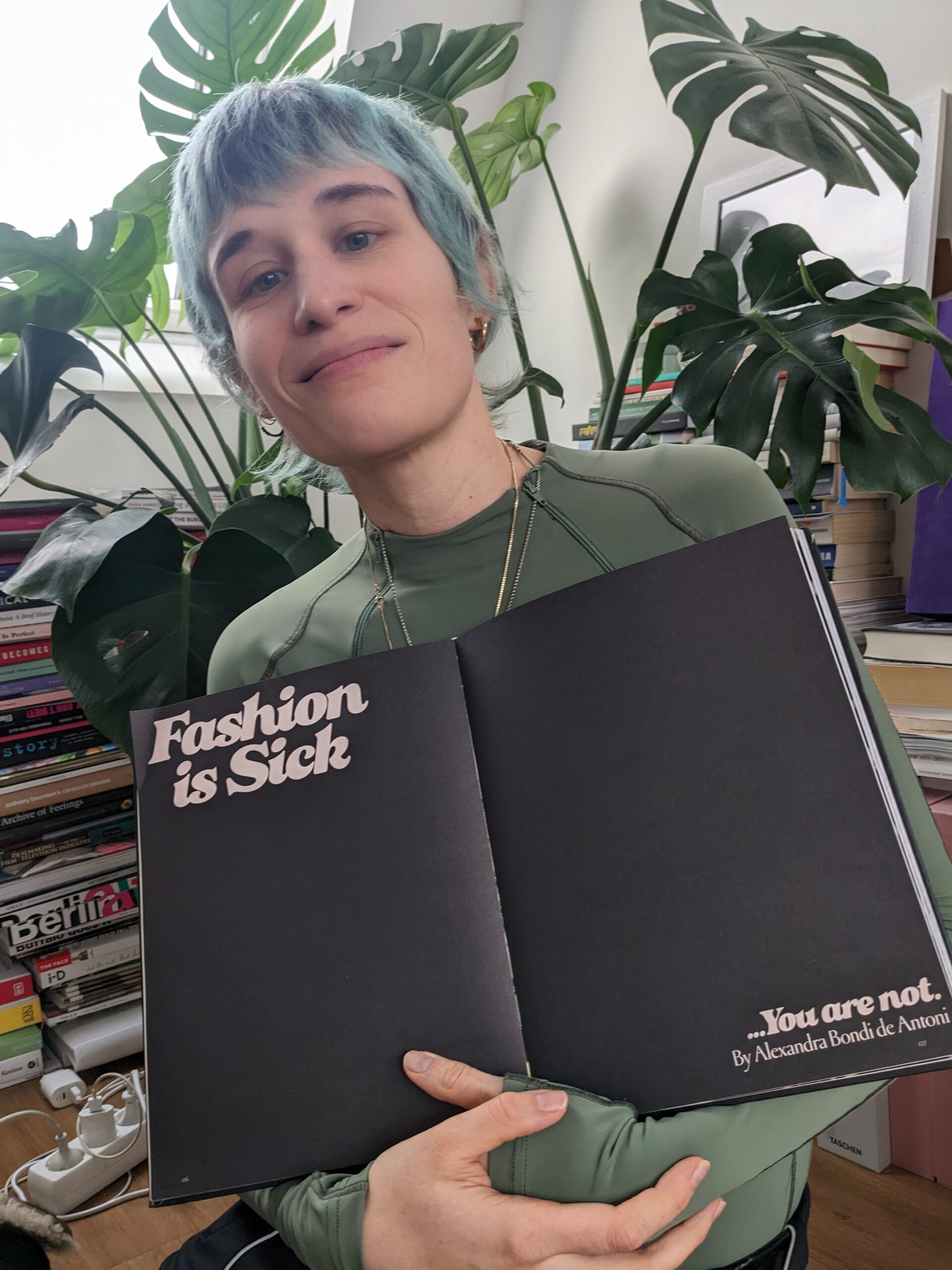

Two years after a career-changing burnout, former magazine editor and photographer Alexandra Bondi de Antoni reflects on fashion’s fraught relationship with mental health.

“Alexander McQueen, Designer, is Dead at 40.”

I don’t remember where I saw the headline for the first time. I read it over and over again and still could not comprehend its full meaning.

“Alexander McQueen, Designer, is Dead at 40.”

The words stayed with me for days. It was 11th February 2010 when visionary designer Alexander McQueen died. I was 19 years old and about to undergo my second round of inpatient therapy for bulimia, as reports emerged that McQueen’s death was ruled a suicide, and that he had suffered from depression.

“Stella had been unwell for some time. So it is a matter of our deepest sorrow and despair that she felt unable to go on, despite the love of those closest to her.” I looked at the words for a long time, not knowing what to do with myself.

“Stella had been unwell for some time.”

Beloved British supermodel Stella Tennant took her life on 22nd December 2020. I first saw the news on Instagram, six months after I left my position as Executive Editor of one of the world’s biggest fashion magazines because I wasn’t able to go on.

“My life is now about coexisting with anxiety and depression, so strategically that I can enjoy the glory that life has to offer.”

I see the words on my small phone screen while researching this essay. In 2018, model Paloma Elsesser posted that she had managed to get (and stay) off pills for the last three years.

Two years after my life slipped through my fingers, I feel heard. For as long as I can remember, I’ve had what I like to call a “special relationship with my head.” As a teenager, I resisted my parents’ numerous attempts to treat my eating disorder. I became really good at lying to psychologists—I did not see the point of sitting through the therapy sessions. I did not understand their problem. While flipping through issues of Vogue, I admired all the skinny models and fashion insiders.

Where I wanted to go, everyone looked like I did.

When I went into the clinic, Alexander McQueen took his own life. I remember how shocked I was by his face, puffy from all the drugs in his system. It spoke of so much suffering. And yet, I read everywhere that he was just a “crazy” creative who couldn’t take it anymore.

At that time, I was too busy with myself to understand that moments like this do not exist in a vacuum. Behind every story is a person overwhelmed by life—one who can only channel their illness into creativity for so long without completely losing control, adopting toxic habits to get through the day or becoming reliant on substances to function. And in front of them sits an audience who demand that creativity flows, that stunning collections are designed at lightning speed, and who demand each new offering is better than the last. An audience who, at the same time, are just waiting for someone to make a wrong step.

In the past few years, major fashion magazines have begun publishing personal accounts by industry insiders like models Adwoa Aboah, who has talked honestly about her drug addiction and suicide attempt, and Adut Akech, who recently opened up about her battle with depression. Both mainstream and trade publications produced well-researched reports advocating for better treatment of mental health issues in the industry and major fashion conglomerates like Kering or online luxury fashion retailers like Farfetch announced initiatives meant to support their employees in case they experience mental health issues.

As with so many other political matters (think women’s rights, fair wages, beauty standards or diversity), it appears that the fashion world—dictated by the dichotomy between business and creativity—superficially understands that it has a mental health problem. But it doesn’t seem to have grasped that mental health issues can have life and death consequences.

When I was admitted to my first inpatient therapy, I met people who helped me realise that I was sick, but also that a healthy life was possible. It took me three attempts, but somehow I managed to stop throwing up every day, and managed to find a new way of living in my body.

A year after I left my last job, I was offered a “once in a lifetime” type of opportunity. It was the sort of position everybody in fashion dreams about. My younger self would have given anything to attach another fancy job title to my name. But, as I was just getting better, I summoned my courage and told the well-known interviewer about my recent mental health struggles. After a silence that seemed to last forever, she looked me straight in the eyes, lifted the corners of her mouth slightly and said in a condescending tone:

“So, you need to take care of yourself now?”

At that moment, it became clear to me that fashion is still driven by the fear that us mentally ill people cannot perform in the way the industry demands us to. Being mentally ill often means needing more time, pills or hospitalisation. Being unwell can mean not knowing whether you will ever think a clear thought again, let alone put one down on paper. There is no quick-fix for mental illness—no simple cure that can be sugar-coated, boxed and sold to us by the well-being industry. Mental illness doesn’t get better by simply working out more or being more mindful— a strategy that the very magazines which uphold these toxic work environments often proclaim.

A year later, my career was slowly gaining some momentum. I published my first photographs on the newly launched i-D website, was featured as an up-and-coming photographer on Dazed Digital and secured more and more writing jobs. At the same time, a physical illness plunged me into such a bad depression and PTSD that I could hardly leave my bed for weeks. I was so afraid my commissions would stop. In my few lucid moments, I used what little energy I had to organise photo shoots and write texts (some for the magazine you are reading). It was too hard to confront my problems, so I threw all my fears, despair and paralysis into my creativity. Almost nobody knew what I was going through. I was too ashamed to fully accept my brain’s limits.

Yet, I played the game a lot of people in the industry are so good at. While I celebrated those who spoke their truth about mental health issues, I was quick to laugh about the drunken PR girl at the party, the drugged-up designer who was unable to answer my questions, or the stylist who disappeared to the bathroom every half an hour to take a bump of coke. My superficial words of encouragement were hypocritical. I watched colleagues suffer and self-destruct, and commented on the process with a bizarre form of delight. I was ready to pounce with scathing criticism when creatives didn’t deliver the game-changing work I hoped they would.

My following years were marked by multiple ups and downs. Like many other mentally ill people, I fell down, got up again, only to fall down again and get up. Sometimes I managed to keep it together for years, sometimes only for a few months, or, if it was really bad, days and hours.

When I look back at this period in my life, I often wonder what kept me going.

Thanks to therapy, I can understand now how my upbringing influenced my ideas around what a “successful” life looks like. From early on, I was told by my parents that making a lot of money and having a thriving career is what I would need to be happy. As if happiness is something money can buy. Simultaneously, fashion was painted as the most magical field to work in. I saw the glamorous and effortless models in fashion ads and I aspired to live the luxurious life of everybody I saw in the pages of magazines. Fashion was my escape from the normal middle class life I dreaded deeply. My ambition reassured me that I was doing the right thing. It all changed again after I started my first permanent job as an editor in Berlin. I was working with an international team, went to fashion weeks, and met people who had always inspired me. For the first time, I experienced what it meant to be defined by my workplace. I wasn’t just Alexa, I was “Alexa from… ”. All of a sudden people who had never noticed me wanted my attention.

And yet, I felt alone and depressed.

This feeling grew even stronger when I went into my last job. I managed a big team, I earned more money than ever before and I lived the fast and glamorous life I thought I always wanted. But the speed of the work environment and the downsizing of ideas for the sake of KPIs made me tired. When the Covid pandemic started, the publisher I worked for decided to focus more on digital content, which made some of the old staff members really angry. Shortly after the world went into its first lockdown, they started to take it out on me. At some point, I couldn’t take it anymore. I left my position and with it, the dream I had about my future. My brain shut down in a way I had never experienced before. For weeks, all I could do was lie in bed. Every other activity ended in a panic attack.

When I got better, I made the commitment never to let myself end up in this situation again.

While I was recovering, Stella Tennant took her own life. I was overcome with a feeling of helplessness—I realised for the first time that the pressures of fashion affect everyone, no matter how famous you are or how much the industry loves you.

It took the severe consequences of my last burnout for me to be able to acknowledge my own fears. I had to accept my illnesses to finally understand that I have to avert my gaze from my own small reality to see the structural problems our industry has with mental illness. It does not matter whether I talk to editors, models, designers, stylists, hair or make-up artists, interns or assistants…

It appears that all of you accept that the work you love has the ability to burn you out.

And yet, all too often these crashes are seen as a part of the process—something that happens to everyone, on repeat, without any significant systematic change. No matter how magical it can be to work in fashion, the structures it’s built on are rotten. Even as more and more individuals are consciously trying to create new ways of working, our industry is still dominated by the expectation to work a lot for almost no money, the pressure to always be on top of everything, run in the right circles, and reinvent the wheel over and over again.

While I want to stay positive, I am scared for the younger generation. I am not sure if they will be able to create a safer space for people to fall down and get up again. Structural change does not happen overnight. I get weary when I think about the sheer amount of creatives who will burn out along the way. What fashion needs is real change and a sincere willingness—especially by its biggest and most influential multi-million dollar players—to slow down, take a breath, pay fair wages at all levels, cut collections and create realistic goals. What creativity needs is room to explore, room to make mistakes, and room to say no. Our industry cannot continue to put the burden of maintaining a mentally stable life on individuals. It cannot go on burning through talent until there is nobody left.

“I need a break, I cannot do this anymore.”

I texted this to my now husband almost exactly two years ago. Nine words that changed my life forever. And no matter how hard it is to adapt to the new way my brain works, I am proud that I am able to write again, and for you to read my words.