It’s January: the time of year when we’re algorithmically and unrelentingly shamed for our “over-consumption” over Christmas. Anti-fat rhetoric is being screamed from every direction—detox ads are rolling into our scrolling, and fitness programs are being marketed with vigour, targeting the pounds we’re supposed to feel guilty for having gained.

When gyms were open—a lifetime ago—I found them to be intimidating and anxiety-inducing spaces. Rife with confusing equipment and judgement, I’d sweat more from hypercritical stares at my bad form while squatting than I would from actual exercise. And I’m not alone—according to a study by Sure Women, one in four women suffer from ‘gymtimidation’, and almost half of all women have at some point felt negatively judged while working out. It’s why I turned to classes—and joined a wonderful community of pole dancers who were supportive and driven by strength over aesthetic ideals.

Though gym culture has evolved, there have been countless reports of women being ogled at or even harassed by male gymgoers and staff. When it comes to cowork-ing out, mixed gender spaces are still a relatively recent phenomenon, namely because any benefit of women’s exercise other than weight loss wasn’t taken seriously until the ‘60s. The fact of the matter is: Gyms were never built to be welcoming spaces for women—and not much has been implemented over time to prevent that.

Though femme-exclusive spaces have been burgeoning over the past decade, even their history is a sinister one—and weren’t always safe havens for women who want to work out. “There are no ugly women, only lazy ones,” said Helena Rubinstein—the same beauty-mogul responsible for the first all-inclusive space for women’s fitness. Her seven-story building in New York dominated Fifth Avenue as a mecca of ‘health’, including everything from skincare specialists to physiotherapists. Workouts were promoted to women wanting to appear ‘slimmer and more graceful’ which equated the concept of ‘reduction’ with fitness, and urged women constantly to find ways to be less.

Since its inception, the world of female fitness has echoed this “reduce” mentality—which is exclusionary and one-track-minded. Women were told that perspiring was unladylike, that fitness would impede fertility and that frailty was fetching. Workout machines of the early 1900s required minimal human effort, and promised to vibrate fat out of existence, because any physical assertion was considered ‘too manly’. Though things have changed, history still haunts our ‘get fit quick’ culture that promotes diet pills, gummies and even lollipops as alternatives to healthy eating for weight loss.

In 1974, an advert for the Elaine Powers gym franchise said: “If you are a dress size 14, you can be a size 10.” The worst part? “Thinspiration” figure Elaine Powers didn’t even exist—she was an imaginary character thought up by the gym’s founder, Dr. Richard Proctor, whose fitness journey was meant to seem “relatable.” Majorly successful studio Slenderella—most famous for coining the term ‘bikini body’—capitalised on the 20th century notion of women’s fragility by promoting “passive exercise,” which claimed women could vibrate their way into looking good in a swimsuit. The same rhetoric is still being peddled, and made headlines in 2015 when Protein World infamously plastered ads across the UK that promised to make women ‘beach body ready’. The ad was eventually removed by the ASA, following a wealth of backlash. Yes, women have long been beholden to corporations who pry on their insecurities and create new ones. Divesting from these harmful attitudes has been key for me in finding the fun in fitness.

View this post on Instagram

When gyms closed last year and we found ourselves bound to our homes—working where we slept and sleeping where we worked, with just one hour of outdoor exercise allotted—home workouts boomed. It seemed as if all of social media, first hopefully, and then begrudgingly, endured Chloe Ting’s excruciating workouts or cleared their living rooms to start “Yoga with Adrienne”.

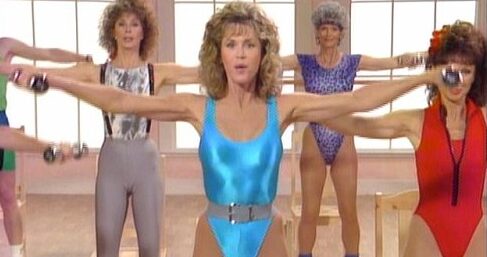

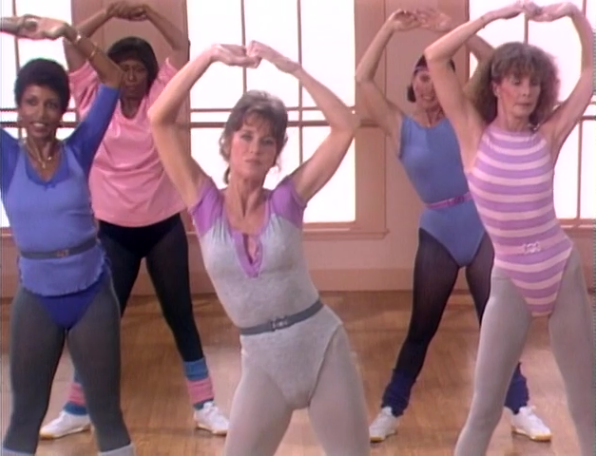

Who would have thought that in 2021 millennials would be taking to their living rooms to mirror the motivational workouts they mocked their mums for doing in the ‘90s? The Peloton trainers and Shaun Ts of the world are standing on the shoulders of petite white women who revolutionised exercise forever—like Judi Sheppard Missett, who built Jazzercise to the second-fastest-growing franchise in the US behind Domino’s Pizza, and Jane Fonda, the cult leader of the revolutionary home workout. Though they mainly catered to white, middle-class housewives, these women offered a joyous, legwarmer-wearing alternative to dreary, testosterone-filled gyms, and were instrumental in merging the world of fitness and celebrity, paving the way for the Popsugars of the future. And where Missett capitalised on the beauty ideals of the time, Fonda actively defied, and rewrote the narrow rhetoric surrounding fitness. ‘Refuse to be afraid that we will no longer be considered attractive and acceptable when we are strong!’ she wrote on beauty ideals. ‘Declare a truce and accept food as a life-giving friend!’

Social media has birthed a new generation of female fitness influencers who have built on the works of Fonda and Missett. And though much has changed regarding the message, one thing still lingers on: the most popular content creators are White and petite. Modern-day fitness is still tainted by the archaic beauty standards of the past. The recent reframing of fitness as ‘wellness’ has given rise—and renaissance—to practices like Pilates, Barre and Pole. And although the perception of what it means to be strong is changing, these forms of fitness are still beholden to images of whiteness as the pinnacle of “health.” (Google “pilates body”, and you’ll see what I mean.) The global commercialisation of yoga—a practice that was once thought to be stealing young white women—has been subject to an overwhelming whitewashing of its delivery and message, when it succumbed to the rampant consumerist culture of the west. From LA’s high-price Kundalini studios to celeb-approved Jivamukti—started by white couple David Life and Sharon Gannon in 1984—the appropriation of yoga has repositioned the practice as by and for white people.

We are seeing the online fitness space dominated by women who look like Fonda and Misett, and anyone that dares to deviate from the norm, no matter how healthy, is met with a barrage of abuse.

When Cosmo revealed its January cover last week featuring a plus-size Black yoga instructor, it sparked instantaneous outrage online—with comments accusing the magazine of ‘trying to kill fat people’ by ‘promoting obesity’. Though diverse fitness professionals can amass huge audiences, they are still unrelentingly scrutinised in wider society and are exposed to greater abuse—regardless of the myths surrounding fatness and health being constantly debunked.

The beauty of online workouts, however, is the freedom of choice—the type of trainer you work with, the type of exercise you’re doing, and the frequency and intensity of sessions. Social media and video-first apps have democratised access to exercise—by massively reducing costs and offering unrivalled flexibility. I decided to support a Black female trainer, @xtinaokenla, by subscribing to her platform, which offers an extensive timetable of classes that never make me feel lost or confused. I’m working out in an entirely new way and feeling better for it.

With our workout choices becoming extensions of ourselves, fitness spaces have become cult-like—with the rise of all-inclusive, members club-style organisations and merch to match. These spaces—though not admittedly—operate on exclusivity. But, in response to a fitness world that was and still is incredibly white, marginalised groups are forming their own spaces. From Black Girls Hike to Black Girls Run, interest groups are popping up that focus solely on fostering a safe space for marginalised people who want to work out—and such spaces, even virtually, have been a salvation during the pandemic. These changes are welcomed, but—when we’re finally allowed to congregate again—the wider fitness community needs to do more to be both inclusive and representative, provide opportunities for those who’ve historically been iced out of fitness. Until then, I’ll continue to be intentional with the fitness instructors and content creators I support—now that we finally have the luxury of choice, it’s our responsibility to use it wisely.

View this post on Instagram