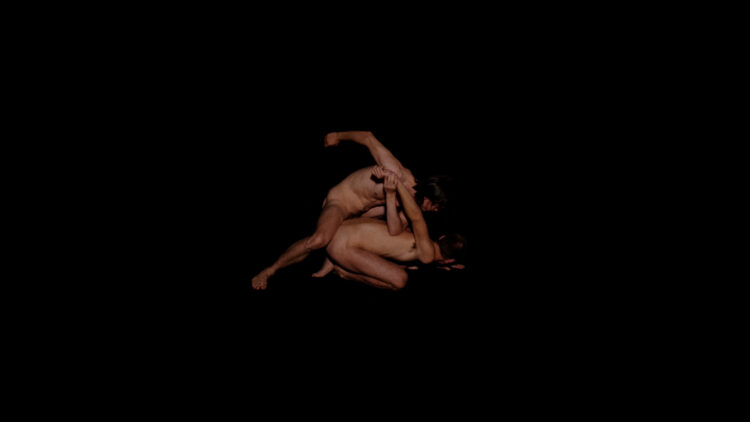

What does it take to make a porno? In the case of the Copenhagen experimental short All Work No Play (Ei Blot Til Lyst): three years, five willing actors and one homophobic hate crime. “I always wanted to explore dysfunctional, toxic masculinity and how men being sensual together could act as a kind of antidote to that,” explains the film’s director Marco Stoltze. “But I didn’t know that that storyline would be so real.” Premiering online as part of Lightroom—a collaborative project conceived by Copenhagen’s MORPH collective and sex-positive community Bedside Productions—the film explores male intimacy and tenderness as a way to heal from hate.

Stoltze dreamt up the idea for his first adult film back in 2016, but his narrative, bittersweetly, came to life when his friend, Copenhagen DJ and techno veteran Marc Helt, was attacked on the streets of Nørrebro. “He got beaten up and called a faggot,” the director explains. “After that, he really felt like he wanted to open himself up to homosexual experience, to rebuild that sense of trust, and that’s exactly what I wanted to do with the film.”

Denmark is known for its forward-thinking, fluid approach to gender and sexuality, and Copenhagen especially is a place where queerness, and its expression, is celebrated. “The younger generation are so much further ahead than we ever were,” Stoltze explains. “Even identifying as ‘gay’ is so old school, you’re just whatever and you have sex with whoever.” Such attitudes paved the way for All Work No Play, and are values the whole Lightroom project reinforces from process to output. Of the film’s actors, three out of five were either hetero-identifying, or inexperienced when it comes to homosexuality (Helt included). There’s a moment in a BTS interview for accompanying documentary Dear Friends, where one performer candidly admits, “I just thought I can’t live my whole life not knowing what it feels like to have a dick in my mouth.”

As Lightroom makes its online debut (its planned premieres in Berlin and Copenhagen were cancelled due to covid), Stoltze sheds light on the measures that go into making an ethical porn film, and why performers-first companies like Bedside should be the future of porn production.

How do you approach casting for a project like this?

It was very clear from the beginning that we didn’t want to go out and convince anyone to be part of the film. I couldn’t go and ‘sell’ it—we had to make people aware it was happening and hope they’d come to us. I didn’t want there to be any doubt of ‘have we talked this person into it,’—it had to be self-initiated. So over the course of a year or so, we had posters at techno parties and made Instagram posts and did a bunch of interviews with people.

What kind of questions do you ask? How do you ensure you’re not ‘talking people into it’?

We talked to them about sexuality and porn and masturbation and all of these things. It was less about the film itself and more about understanding how confident they were in their sexuality, and why they wanted to do this. As soon as you were sitting with somebody who was a bit too young, either literally or experience-wise, you could feel you were getting into some kind of grey area with regards to their motivation, the desired outcome, or the expectation. If we were in doubt, Anne Sofie, our producer, would have a deeper conversation alone with them about how it feels to make a porn, to have it come out to the public, and the worst case scenarios of that. I think we talked to 20-25 people.

Was their sexuality important to you? Did it matter how they identified?

Initially—which is now over three years ago—I had a much more binary vocabulary, so we automatically discussed a lot using the terms gay and straight. During the process it became less and less relevant for the project. I think being in such a devoted process about sexuality has really made space for my own sexual identity to become more fluid and non-binary and ultimately it became a key part for the project that we should never articulate these simple “preferences”.

How did you create a space safe enough to encourage the performers to open up to this kind of sexual intimacy with one another?

The point was that for the big sexual scene that they shouldn’t know each other too well, and it should be kind of a first time experience, but we also wanted them to feel safe and comfortable. We broke them up into smaller groups, and they did photo sessions with Birk [Thomassen] together. That was a way for them to form some kind of intimacy, so they would come on set having a trustful relationship with at least one other person.

And for the actual sex scene, how did you approach that?

That day was one of the biggest achievements of this whole project, I think we really managed to create a safe environment. The performers slowly drafted in and then they went one by one into the room where we were gonna shoot, and did an informal interview for the documentary, to put some words to their feelings. Then we all did some meditation together in the room to try to put calm energy into the space and really make it feel safe, and took it in turns to talk about expectations, worries, boundaries, hopes—all of that.

What were their worries?

The main fear was of overstepping other people’s boundaries. But because that got articulated so clearly, people could react instantly and be like ‘I’m not worried about you overstepping my boundaries, and if you do I will just tell you.’ It kind of ruled out a lot of those things that could make it hesitant or staccato.

Who was in the room for the actual filming?

Basically just the cinematographer—we had the sound person mic up the room and then leave, and then Anne Sofie and I were sitting outside with a monitor that got overheated because it was so hot [laughs]. We couldn’t really even see what we were shooting, but we would peek in once in a while. Somehow it made sense, since this wasn’t about my fantasy, but instead their spontaneous experience. I couldn’t wait to see the material in the editing room afterwards.

How long do you plan to shoot a scene like that?

We’d planned four hours for the filming and we thought it would take them a while to warm up, especially since some of them had never had this kind of experience before, but after about five minutes, there was a party in there [laughs]. It was amazing. We were a little bit nervous that it might be awkward, so we had made this list of like different things they could try—from tender touches to sexual acts—we wanted to give them some kind of inspiration if they didn’t really know what to do. At some point they were reading from that paper like, ‘we already did all this.’

How did they reflect on the experience afterwards?

Immediately after, they were euphoric—similar to how people on MDMA would act, but just so much more pure and clean because it was just such a sober, direct, intimate experience. Then, very naturally, and kind of in the same way as MDMA actually, because you’ve been so over-stimulated, you have that kind of thing where you dive down and feel slightly empty and need time to regain yourself. With Bedside, we really tried to prepare them for that beforehand, and make sure they felt supported and cared for after.

Was the process healing for Marc? What do you see as the ‘moral’ of this story?

It was, but I don’t want to glorify gay sex, or say it’s the ‘solution’. In the end I cut out all the blow jobs and sexual things that Marc did in that scene, because it’s more about him being in this space, exposing himself and being vulnerable. The film is about tenderness and openness—being willing to trust others, and open yourself up to their care. I think this exposure and these new spaces for men to communicate can be a great tool for their mental health and masculine identity.