It might seem strange that the main sponsors of Germany’s biggest (and only) afro hair convention are beverages, not beauty brands, but its founder, Nana Addison, was not surprised. “The German beauty industry is racist,” she says matter-of-factly.

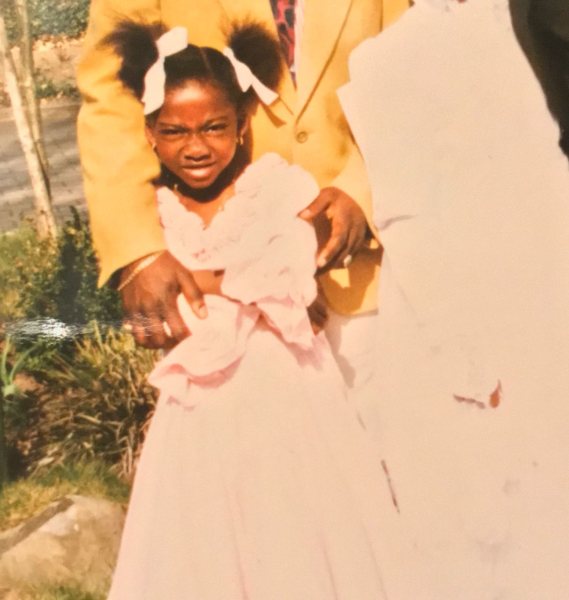

Born in Ghana, but growing up in Essen—in one of the only black families in her town at that time—it’s something the now-30 year-old has experienced first hand. At seven, she received stares in the playground for her braids that stood up on end. At 13, she struggled to access products for her hair and skin type. At 28, she was rejected funding for CURL, her business dedicated to black hair. In April this year, she was one of many outraged by German drugstore Rossmann’s decision to publish a photo of an afro accompanied by the hashtag #badhair. Like many other professionals, Addison has experienced racism—both overt and subtle—as a persistent force plaguing German beauty.

When she set out to found CURL in 2018, Addison received little industry interest. Though she recognised the dire need for diversification, and for black-owned and -orientated beauty endeavours in the German market, she couldn’t prove the demand with data. “After World War II, Germany vowed not to collect data on ethnicities,” she explains. “It was well-intended, but it doesn’t serve black people—we cannot know our numbers or prove our market is valid.” Instead, she self-funded CURL with 300 euros, and has since scaled it into a 1000-strong community, making it the biggest event geared towards black hair in Germany (and the DA-CH region), and reached 50,000 euros in revenue—without the help of the German beauty industry.

Amid an unexpected COVID-halt, preparations for a virtual CURL event later this year, and the running of her creative agency, we caught up with Addison to talk about the growing black-orientated beauty market and the realities of racism in the industry.

View this post on Instagram

What role did hair play in your childhood?

Growing up in Germany, as the only black girl in the suburb, hair was a big factor. I was already drawing in so much attention as the immigrant, and as a black person my hair and skin identified me as different from everyone else. Hair came to represent how I identified myself and everything that I considered as beautiful. I couldn’t really connect. Everything I saw on television and media was predominantly white, blue-eyed, and blonde—everything that was not me.

Where did you feel most represented?

I had this really cool uncle in New York who used to send us VHS tapes of MTV Raps. Me and my sister used to watch them and be like, ‘Oh my god, where is this, we need to look like this and we want our hair like this.’

Who did your hair growing up?

My mum—it’s kind of a Ghanian tradition. But she wasn’t very talented at it—she grew up in an affluent household and always had a hairdresser. She worked full time cleaning other people’s houses and didn’t really have time for the whole ritual that comes with taking care of black hair. When I started going to kindergarten, there were no products available for our type of curl pattern, so she would do little braids and things, which also felt difficult because no one would understand why my hair looked like a tree. In the end, like many black people in Europe, she got me a chemical relaxer. Not necessarily to assimilate to a western beauty standard but more to manage the hair.

Was that a significant moment for you?

For my understanding of identity, it was very significant—and in a negative way, because I felt like my hair was only beautiful, or acceptable, when it was straight. I never associated hair in general as something to play with. All my white friends would change up their hair—dye it or cut it short or put curls in it, and this was all for play, but I never really had that experience. For me it was something that people associated my race with or something that was not manageable or acceptable, just struggle. My mum would sigh when she would have to do my hair, I would cry.

When did you start thinking about hair in the context of your identity?

When I got to secondary school, I was allowed to go to the city. My social circle changed and I had many more black friends and friends of colour, and I had more of a chance to really explore my identity as a black person. My household was very traditional Ghanian, so I had always known my heritage, but I didn’t really fully understand the construct of blackness until I made these friends. My entire lifestyle changed. I would listen to different music, and was exposed to different things. As migration rose in Germany, afro-shops started to pop up. I was lucky enough to find them and from there have conversations about hair. Then, when I was 16, I went to London.

What changed in London?

My whole perception of who the fuck I was! I was like ‘woah what the hell!’ There were so many black people from everywhere—from Jamaica, Haiti, the islands, from Africa from everywhere—diversity was such a normality. I know the UK also has its challenges, but it was still much more developed than in Germany. It was just such a fresh breath of air, I was just one of many black girls. There were so many afro-shops, and they weren’t called afro-shops, just the beauty supply store for black people. Suddenly there were so many products for me. For me, London was a centre of identity and confidence. London taught me to fully love who I am, you know? Fully love my ethnicity and not see it as deficient.

Do you think that paved the way for CURL, wanting to be able to pass that feeling on?

Definitely. My natural hair journey happened when I was 17 or 18. I decided to shave my hair off and let it grow out naturally, and it was such an amazing, liberating experience. After I grew out my afro, I cut it short again and rocked a Halle Berry look for a little bit, and then I decided to shave it off again. That’s when I started to realise that my hair was no longer controlling me, controlling my sense of beauty, of identity. I wanted other people to feel that power.

Where did the idea of a community-based event come from?

It actually started when I went to this workshop in Frankfurt—Rock Your Curls Academy. It was a small one-time event run by Felicia Leatherwood, the head stylist of hit HBO series Insecure, and a woman who is just really passionate about her natural hair journey. A lot of people of colour who are well-known in the German hair and beauty scene were there. I think this workshop was the catalyst for a lot of people like Fresh Prince The Barber, THE Instagram barber. That day we spent with her she was just feeding us self love, self acceptance. I realised everything she was teaching us about managing our hair doesn’t mean anything if we don’t love ourselves. On the way home, I said to my sister, ‘we need to do this, but we need to do this on a big professional, well-produced scale in Germany so everyone can access this.’

How did you go about that?

I think everything that I was doing professionally was helping me grow CURL. I was working in event management, then brand marketing and consultancy. I founded my first company, and I was travelling around the world—I was at all these events in different industries for tech, fashion and other co-branded events to launch products. I felt like there was a lot of momentum in Germany.

But this momentum was being ignored by the mainstream?

Exactly. There was this big scene of influencers that people weren’t recognising—they would still go ahead and book black influencers from the UK, although there are lots of influencers in Germany that have the same amount of followers. By this point I had a lot of leadership skills, I could manage huge teams of 50-100 people, I knew how to do ground work, build something up from nothing, and I felt ready. My network was big, I knew all these influencers, and it was really easy to activate them, because I had built up so much momentum I guess. There was also a level of respect from the community—even if they didn’t understand it, they knew I do what I say and say what I do. The benefit of the doubt was a huge factor for the launch I would say.

View this post on Instagram

CURL is also geared towards the industry, and filling the space that has been neglected due to racism…

Yes! It’s B2B B2C, meaning brands can rent vendor space and present their brand to regular guests, but also retailers who are interested in expanding their collections to tap into a new market, can also see the brand, talk to them and hopefully add it to their stocks. I want all the products for black people to be just as accessible as products for white people. I want there to be a marketplace where people can buy instantly—but the whole goal is to get them into retail shops and to facilitate that exchange without the hesitation of saying or doing anything wrong. I want to help brands overcome their initial ‘I don’t know how to handle this kind of feeling.’

And this educational aspect—teaching people about black hair—is also a major part of CURL.

Yeah, that’s the cultural and lifestyle side. We have a main stage with a programme all day, with panel discussions, keynote talks and artist performances on topics that are around the culture of people with curly hair. We have professional hairstylists teaching how to care for natural hair. It’s the topics that are interesting for them but also for friends of us. If you’re a supporter, a partner, girlfriend, or a white parent with a mixed race kid who wants to learn how to do black hair—you are just as welcome.

Why are black-owned beauty businesses so important?

I think there’s a huge opportunity for black entrepreneurs to start companies that serve the hair and beauty demand of BIPOC people in Germany. It would be beautiful if the community who are experiencing the lack could also be the community who fulfil the niche on a business level. This is what I want to support and encourage. The worst thing would be for non black and brown people to finally discover this market in Germany and then start businesses that cater to it—for the money to come from black and brown pockets into white ones.