HAVING LONG LINKED SCIENCE AND FASHION, DESIGNER IRIS VAN HERPEN SPEAKS WITH CERN’S FORMER CULTURAL SPECIALIST ARIANE KOEK ABOUT THE POWER OF COLLABORATION, THE STATE OF CREATION—AND THE NECESSITY OF FAILURE.

Iris van Herpen’s work is at once strikingly unpredictable and strikingly consistent. Unpredictable because, with each collection, the Dutch fashion designer questions and ultimately pushes the parameters of possibilities within her craft, both technical and technological. Consistent because these daring design endeavours are far from simply being one-offs—van Herpen stuns every season. Her work is consistent in its unpredictability.

At the core of this challenging of industry norms lies a profound interest in science and innovative technologies, which van Herpen already developed while studying fashion at ArtEZ in Arnhem. Founding her label in 2007 at just 23, she was invited to show as part of the official haute couture calendar in Paris just four years later and became the first designer to present 3D-printed dresses on an haute couture runway. Since then, the now 36-year-old’s work has become almost synonymous with distinct dichotomies: Technology and haute couture, science and handcraft, futuristic concepts and fantastical clothes.

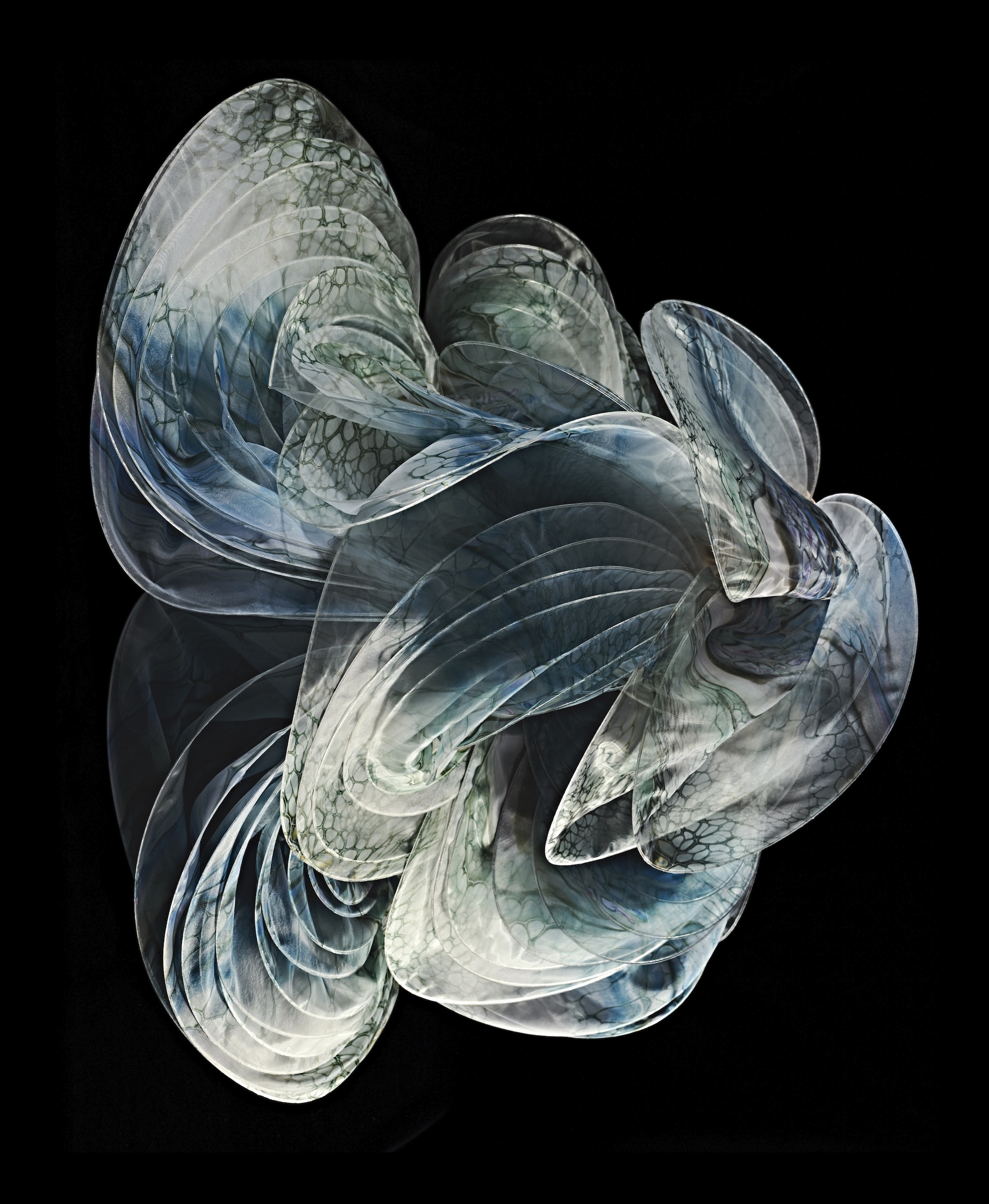

Take, for example, her current collection Sensory Seas, which was shown in Paris at the end of January and is depicted on these pages. Van Herpen, with the help of her team, constructed shell-like dresses by laser cutting pearlescent exoskeletons, and later hand-embroidered the pieces with 3D laser-cut silk dendrites. In prior seasons, she had built dresses out of metal but made them look like clouds of dust.

Leather was layered in a way that resembled landscapes observed from a plane window. With a hot air gun and pliers, she once imitated water splashes, draping the material around the body as if frozen in mid-air. The references for her designs range from being as tangible as metal wires to the pretty intangible flow of digital data. But the designer never interprets them in a literal way—van Herpen would much rather bend matter and matters however she likes.

Especially when it comes to the matter of fashion beyond clothing, of fashion being an expression of creativity and cooperation. One of the designer’s most shaping collaborations has been with CERN, the European Organisation for Nuclear Research, based in Geneva. In 2014, Ariane Koek, then the laboratory’s cultural specialist, invited the designer to take part in the visiting artists programme she had established at the institution. Having received a Clore Fellowship in 2009, the former BBC producer set up and then ran CERN’s first arts policy from 2010 until the end of 2014, striving to facilitate precisely this fusion of art and science.

Van Herpen went to CERN in 2014 and based her SS 15 collection Magnetic Motions on the experience. It isn’t difficult to comprehend why the designer was so taken by CERN: Where scientists investigate the unknown, van Herpen translates questions into design. The former accelerate particles via the Large Hadron Collider, while van Herpen accelerates creativity.

Coincidentally or not, her delicate dresses often appear to be visualisations of physical theories themselves. Look up ‘the butterfly effect’ or ‘chaos theory,’ and you will encounter graphs made up of millions of lines, astonishingly similar to the multilayered silhouettes van Herpen creates.

‘The butterfly effect’ describes, simply put, the way in which one small change to initial conditions can trigger an unpredictable set of changes. Take a laser cutter instead of scissors, or a 3D printer instead of a weaving machine, and you just might end up with a design that puts the very definition of the discipline it occurred from into question. Fittingly, when 3D printing something, van Herpen says she never knows exactly what the outcome will look like until she receives the finished piece. There’s beauty in theories of chaos.

In an increasingly self-centred world, there also is no denying the need for precisely these collaborations and challenging of norms. Since their initial collaboration, Koek and van Herpen have stayed in regular contact: Koek attends the designer’s shows, and they often have conversations about topics or themes they find especially interesting. A few days after van Herpen’s Spring/Summer 2020 show, INDIE sat down with them in Paris to discuss technology and creativity, and how both can benefit each other.

Ariane, what was your first impression when you discovered Iris’ work?

IvH: She hated it. [laughs]

AK: I remember seeing ‘The Splash Dress’ and thinking “how on earth did that happen? And out of whose mind?” [laughs] There’s that moment when you see something and it gives you a spine tingle, and you feel your senses going ‘ugh!’ I just found myself electrified by it—in terms of the poetry and the technology as well as just the sheer daring to engage with nature on that level.

At the time, you were at CERN and had established a visiting artists programme. Did you immediately know you wanted to invite Iris to collaborate?

AK: It was really funny because I knew had to leave CERN at the end of 2014. My contract was fixed for five years. And you have to give yourself presents in life for when you’re leaving something that means a lot to you. So the present to myself was inviting Iris to come to CERN— that’s the first time you’ve heard that, Iris! I made a promise to myself that I would get Iris on to CERN and CERN would end up somewhere on the catwalks of Paris.

Which it did. After your visit, Iris, you based your SSI5 collection Magnetic Motion on the experience. How did it induence you at the time?

IvH: I could not believe the invitation; it was pure excitement. I wasn’t aware that this programme existed and that they would even be interested in having artists over there.

AK: I still remember that day you came and looked at the detectors, and how we went backstage. We literally went behind where people don’t go—and still haven’t gone—to one parti- cular detector. And I felt as though it was a homecoming for you in some way?

IvH: Completely. Visiting CERN for the first time is one of the most precious days of my life.

What made it so special?

IvH: Often when people receive my work, they say, “It feels like going into a different world.” And I don’t have that with my own work, because it’s my world. But that’s what I felt when I visited CERN—it’s a world I feel very close to, but that is so otherworldly at the same time. The homecoming is a nice way of saying it. I felt so precious to see the work of these people and was very inspired by the strength that goes into this massive project and the collaboration involved.

How did you go about turning your impressions at CERN into clothing?

IvH: It happened on a very conceptual level. The subjects that are being researched at CERN and the technology and the craftsmanship are so huge that it felt impossible to translate all that into a collection. So, at first, I just took a very personal approach to it, translating the emotion I got from my visit. And then, further down the process, it became more concrete.

You implemented laser cutting and injection moulding, for example, making dresses emulate the magnetic forces of the Large Hadron Collider.

IvH: I collaborated with an artist who works a lot with magnetism. We took a material that was liquid to complement barbed wire, in which we then put metal powder and magnets to create the structure. So we were able to both pull and repulse. The detailing within the growing liquid, on the other hand, couldn’t be controlled at all. So it was actually magnetism that designed the details of that material.

Ariane, was it always as easy for the visiting artists to adapt to the technology used at CERN as it was for Iris?

AK: I think, as Iris says, it’s an emotional and personal response that’s individual for every single artist. The most beautiful thing is that you engage with your mind, your body, your soul, and your heart when you see something so awe- inspiring. But it’s not just the technology. It’s also the minds of the physicists, which I always think is incredible.

IvH: And also the devotion that goes into it; it’s such a creative process. People really live for it there and you can feel that. And I think that’s something that really touched me.

AK: Which is why it was a homecoming, because you’re practically the same! [laughs] You’re totally dedicated.

In articles on your work, Iris, your atelier also often gets described as a laboratory with a lot of research and experiments taking place. Do you agree with these descriptions?

lvH: No, I always go against that, because some people literally think my atelier is a laboratory for some reason. [laughs]

Would you say the way in which you approach research and develop a collection could be compared to how scientists might approach an experiment, though, as Ariane just suggested?

IvH: On a conceptual level, there is some comparison, yes—this extreme eagerness for the unknown, and the drive of search. What materials do I not know? What transformations can I discover? And what movement is out there that I have never seen before? But on a practical level, it’s so different. When you walk into the atelier, it’s pretty much like an atelier. Of course, collaboration and experimentation are much more prominent and much more active in our atelier. So there is a difference with traditional ateliers, but I wouldn’t say it’s a laboratory.

People have their own imagination. When they see the work, they simply don’t understand how it’s made. So I get why they link that. We even talked about doing a mockumentary about it.

Showing fashion designers boiling up dresses?

IvH: [laughs] Yes, we are not boiling up dresses. I always have to calm people down. It’s not like that. I haven’t made a dress in the Large Hadron Collider—unfortunately!

I would assume that one of the biggest challenges of connecting two disciplines thought of as being as contrary as fashion and science, is language. As soon as you implement a word from one into the other, all connotations get transferred as well, no matter if they still fit or not. But obviously, often it’s hard to break through these…

LvH: …boundaries.

Yes, boundaries that have been established for years, or techniques that have been used for centuries. You started showing 3D-printed dresses as part of haute couture in 2011, which often is associated with, and stands for, quite a contrary idea of craftsmanship. How did the industry react to your designs back then?

IvH: I remember the very first collection; people just didn’t understand. Of course, I explained the technique, and it was written down in a press release. But because it said that the dresses were printed, people thought they came out of a printer. So, literally there were reviews of ‘the paper dress.’

There’s a quote from Ludwig Wittgenstein that is quite fitting: “The limits of my language are the limits of my world.”

IvH: Yes, it’s all about language. ‘Printer’ must mean I printed sheets of paper and put them on top of each other. But then the language around 3D printing started to appear everywhere, and I didn’t have to explain it anymore. Otherwise, I think it would have continued to be like that. Sometimes it takes time to get people out of their routine of phrasing and communicating.

“Only through failure do you learn.”

Ariane, during your time at CERN, did you notice reservations or misunderstandings similar to what Iris just spoke about?

AK: I would say absolutely. In the beginning, there was scepticism about this British woman who had this dream to create an arts programme at CERN. [laughs] I remember everyone going, “oh yeah, right.” I was in Kosovo during the Kosovo War, and I’ve always said it’s easier being in Kosovo than it was doing what I did. And that wasn’t an exaggeration. But I was so deter-mined to make it happen, and so passionate about the project, that nothing was going to stop me. Then the director general was like, “yes, go off and do it. And we will give you the time and space to do it.” And now it’s ten years actually since it began.

Science also entails quite a particular vocabulary. How much was language an obstacle when it came to pushing the boundaries of the institution and making it more accessible to people not as familiar with the vocabulary?

AK: Well, I’d say CERN is like a kind of language factory.[laughs] I sat in on lots of lectures with people talking about things like ‘wimpzillas,’ for example, or ‘sparticles.’ And even though I didn’t understand the math, or the language, just listening to those words triggered my imagination. It can be a jumping-off point.

Because when scientists talk, they’re always talking in metaphors anyway. So they’re always substituting the thing. It makes you realise that language itself is a complete metaphor. Because that bowl [points to a bowl on the table] is only replaced by the word ‘bowl.’ Once you get to grips with that, it’s fine and you don’t panic, and you try and find ways of connecting. But it’s also good to recognise that the ways of not connecting can be incredibly little, almost like wormholes. You can go through them and they take you out the other side into some world you’ve never imagined, and by this, they will have taken you further.

That’s quite similar to the approach we have as children when we 9till make up our own minds of what certain words could or should mean.

AK: Absolutely. I always say we have to return to that childlike state of creativity. We weren’t afraid of falling down. We began our lives in experiment— we were physicists, artists, experimenting every time we kind of tried to stand up, or get away from crawling. We fell down all the time. Only through failure do you learn.

“I always say we have to return to that childlike state of creativity.”

It’s quite interesting you mention ‘failure,’ as fashion and arts often make it seem as if failure needs to be avoided at all costs— it’s very much about achieving the goal in the quickest way.

AK: I think failure is essential. But you don’t hear about the failures. And it’s the same with science. Julius von Bismarck, the first artist in residence at CERN, did a video piece of all the failed rocket launches there have been. If you look at that, you realise that, for one rocket launch, there were how many failures? And how many lives lost?

We have this fiction that the world is completely perfect. That Iris’ dresses came out of a laboratory magically, out of test tubes somehow. [laughs] Or that we discovered black holes through some kind of amazing…

IvH: Ping! For me, losing control has been a conscious decision at times. I definitely have the aspiration to control every millimetre, and that’s also part of the design. But then it’s also about how to bring back chaos into the design process.

AK: There’s so much trial and error. Behind every single perfect discovery is so much failure. I mean, some of the artists at CERN worked for 50 years to have one experiment. So in their lifetime they will possibly only have one experiment. And it’s not even guaranteed that they’re going to be on an experiment that is meaningful or discovers anything. But they’re contributing to the bigger picture.

When it comes to fashion, 50 years is an incredibly long time. Iris, you show twice a year during the haute couture weeks, which are roughly six months apart. So your creative process is embedded in a very definite structure. Does that hinder you or is it helpful to have these deadlines?

IvH: It’s really, really good. My mind and my opinions are always transforming, and for me, nothing is ever finished. That’s a blessing and a curse. The deadline of a show makes it possible for me to stop something. But I also don’t have set boundaries around the collections anymore, because the process is pretty chaotic in my atelier. For example, two months ago, I started working on something that I knew was never going to be finished before this show. We just work on it, and it might be ready for the next show, or maybe even the show after that. So it became a very dualistic working process of different timelines at the same time.

How did you get to this point?

IvH: I learnt that throughout my collaborations, because most disciplines or most people that I work with are not so constrained by time as I am. If I want to work with an architect or even an institute, then I have to let go of these deadlines. I just have to continue working on something, no matter when it’s going to be finished. It’s much more ofa forwards-and-backwards; it’s much more like a labyrinth. That’s also something I miss in fashion, or even art. Science is so collaborative; people really have a common goal, and they work together from all different cultures and countries. That synergy is really special to me. I hope that we will grow more into other disciplines as well.

“We need to be open to eachother, and curious, if you don’t want to change, then you shouldn’t collaborate. But if you’re open to a little bit of chaos, of lack of control, then collaborating can be really fruitful.”

Do you think collaborations—especially between fashion and science—aren’t explored as much because people are scared of the failure we just spoke about?

IvH: Yes, I think it’s the efficiency we discussed. Maybe that’s also one of the values of being a small company, a small atelier: You can take bigger risks. There’s strength in small.

AK: Although, some universities are now working with fashion and science much more. So it’s going into the education system. If you look at the Imperial College in London, for example, you’ve got fashion students attached to the university. There’s one person who’s created an outfit that grows with your child. You no longer need to change clothing. [laughs] Which I think is brilliant!

What is most important when it comes to bringing together people from different disciplines? How can collaborations be truly fruitful?

IvH: I think interest is most important. We need to be open to eachother, and curious, if you don’t want to change, then you shouldn’t collaborate. But if you’re open to a little bit of chaos, of lack of control, then collaborating can be really fruitful.

It goes beyond a practical goal. It sounds cliché, but it’s about inspiring each other.

AK: And it’s about excitement as well. It’s about the excitement of discovery and pushing further—not standing still.

IvH: You can also really challenge each other if you have that energy together. I’m a person that always wants to push myself, but when you find someone that does that as well, and you sort of go on top of each other, that opens up a new path.

One person you have collaborated with a lot over the years, Iris, is architect Philip Beesley. In the current collection, you used a screen-printing technique that you and Philip developed together, which creates a dress out of mesh layers. How did this come about?

IvH: There have been so many steps. That has not just been the work of one season; it’s a build-up of many years.

AK: When I looked at that, I went, “oh my goodness! That’s just Philip and Iris even further in terms of the pleating and the amount of work that dress will have taken.” I mean, how much work did that take?

IvH: It was crazy. It was one of the first pieces we worked on. So it has been five months. And the only way it actually happened is because we sent someone from our atelier to be within Philip’s atelier for six months. Often people are connected and communicating, and we are travelling and send samples and skype. But that’s different from actually having someone there with all our knowledge who has been working on the collections a few seasons. That really benefited the collaboration.

What else did you want to focus on with this collection?

IvH: I have known them for a while, but I wanted to finally take some of the drawings of [Santiago] Ramón y Cajal into my work.

A Spanish neuroscientist who did depictions of the human brain.

IvH: I think there’s only a few people in history that have been able to balance art and science so seamlessly. It felt really special to put that into structure and fabric. Another world I wanted to sort of put next to it is the deep sea. That has also been a long-time inspiration, but I never really dared to take it into my work more literally.

What held you back?

IvH: Maybe it didn’t really feel conflicting enough conceptually? Often in my work, I need some awkwardness or some things that aren’t right. And when I look at the deep sea, everything is so perfect. But at the same time, it’s a really good com- parison to our minds, in the sense that we hardly know anything about the deep sea. There’s only five percent that has been discovered.

“It has become such a commercial big industry. It feels the artistry is gone a bit. And that’s what also creates a lack of innovation and pushing craftsmanship further.”

How did you link both?

IvH: I started connecting the deep sea to our own sensory system and the way Cajal was discovering the way we think and the way we connect our brains to the rest of our bodies. Then I felt I could sort of blend the micro and the macro together, and it felt more balanced—the deep sea and our inner bodies were evolving into each other. The power of nature must be so prominent within the process of CERN as well, Ariane, as you’re looking for nature. It must be such a leading force within every experiment that has been done there.

AK: CERN is all about unlocking the secrets of nature. And I kind of see your work as doing that as well. You’re looking at matter and just push- ing it constantly. I was looking at your work the other day and thought, “oh my god, you’re even pushing it to the point of invisibility.” So the material becomes immaterial. You can see that in this collection—actually, in every collection since CERN. Before CERN, it was about structure. And then after CERN, it was all about pushing it to… yes, immaterialise, almost.

IvH: That connection between the material and the immaterial is something I’m always fascinated by. Creating an immaterial dress sounds very abstract. Maybe it’s a fantasy that will never actually happen, but it can spark something in between. The pieces from the new show are all material but definitely part of a search for the space in between. The transparency, the layering, and also the connection to the motion of the body have become such strong focus points for me. And I’m very sure CERN was that initial spark that accelerated that focus.

Iris, in an interview, you once said you want your designs to pose questions. Which questions are most important to you right now?

IvH: One thing that feels important to me is being part of the evolution of craftsmanship within fashion—within femininity and the way we express ourselves. Fashion is communication that goes beyond speech; it’s a very personal language. But sometimes, when I look at the world around me, it feels like that language is a little lost because it has become such a commercial big industry. It feels the artistry is gone a bit. And that’s what also creates a lack of innovation and pushing craftsmanship further. If you look at a lot of what is being made, it’s still the same techniques that were discovered a long time ago. But craftsmanship has always been about innovation, pushing the boundaries. It feels that fashion, in the last few decades, has grown into being more and more focussed on mass production, and I hope that balances again.

If both of you had to pinpoint the greatest benefits technology and science can have to this landscape of fashion, what would they be?

IvH: Sustainability.

AK: I would say the same.

IvH: It’s my number one; it’s very needed very soon. Of course, it’s also still about design but much more about “what do I want to bring to the world?”

AK: Yes, it’s about how we contribute to the world. If you think of our accelerated foot forward and what we’re doing to the world now, it’s a way of… kind of decelerating that.

IvH: Another benefit would be a true collaboration with nature. It doesn’t feel like we are anywhere close yet. We produce a lot, or we take things from nature, but we don’t collaborate with nature. We really have to learn different ways of making. We have to learn creativity in a completely new way. And I have no idea how quick this evolution will be, but I definitely know it’s going to be better. We will dis-cover better ways of being part of that circle. I really think, by the end of my life, fashion will have evolved into something I cannot imagine today.

On the other hand, do you think there’s something within the approach of a fashion designer that science and technology can benefit from?

IvH: I would say more the other way around, to be honest. [laughs] But of course both worlds come back to creativity, or creative thinking.

AK: Perhaps science and technology can take from Iris the understanding of the human body, and the way the human body moves. Science and technology can often remove themselves from the human body to an incredible degree, to the point that everybody becomes big brains walking. [laughs] So, just looking at Iris’ work moving on the catwalk, there’s so much understanding of the physiognomy, but also of the way skin interacts with fabrics.

Also, I think science and technology are scared of imagination. And yet, imagination is within the folds of both science and technology. Einstein dreamt about the theory of general relativity. He imagined it. And imagination takes you further in all things.

“We don’t collaborate with nature. We really have to learn different ways of making. We have to learn creativity in a completely new way.”

What does the word ‘future’ mean to you?

IvH: Future to me is actually now. Which excites me, in the sense that I feel really blessed to have an atelier and to be able to create. It’s a luxury not everybody has. Everything that we experiment with is a direct link to my near future, and I feel that very strongly. It’s very much that I’m continuously creating my own path in that sense. But, in general, I don’t like thinking about the future. Everything that I’m thinking about now is always very connected to one year or half a year in front of me. And that’s the sort of timeline that I feel really inspired by.

Are there any particular research projects or techniques you’re currently looking at that you want to explore or engage with more?

IvH: Yes, but I like doing it before I talk about it.[laughs] I really believe in doing before sharing.

AK: I can understand that. I always say, with that sort of stuff, that it’s all in the doing. It’s always about the process.

IvH: It needs to be this little secret or personal excitement that I dive into. But by talking about it, it becomes reality, and then I lose interest.

Would you say in fashion there is currently too much talking and not enough action?

IvH: I think it’s the Internet; people really like sharing the concept of what they have done. But it’s more of a concept than what they have actually achieved, and I really want to be the opposite of that. Because once you say something is your goal, it manifests as your goal. And I want more freedom in my work.

“The truth is, everything is messy—life is messy, creativity is messy. It’s full of failure, triumph, anger, frustration, chaos, control. But I think we are becoming increasingly frightened of the truth.”

AK: There’s real life and virtual life, isn’t there? Real life is everything we just discussed, which is the failure, the discovery, the pushing, the pulling. And virtual life is one of polished perfection.

IvH: A lot of fantasy.

AK: The truth is, everything is messy—life is messy, creativity is messy. It’s full of failure, triumph, anger, frustration, chaos, control. But I think we are becoming increasingly frightened of the truth. At the moment, we keep on trying to control the way we perceive things. So, when you say “too much talking,” I think there’s too much projection and too much finishing. As in—almost like fashion finishing—creating a perfection that doesn’t actually, and shouldn’t, exist. Because the world itself came into being through chaos and collisions.

Photography PATRICIA KHAN

Styling ISAAC PÉREZ SOLANO

Model ANNA PADHORNAYA

Thanks to TOBIAS HEINRICHS and PAULINE BIANCHI at IRIS VAN HERPEN