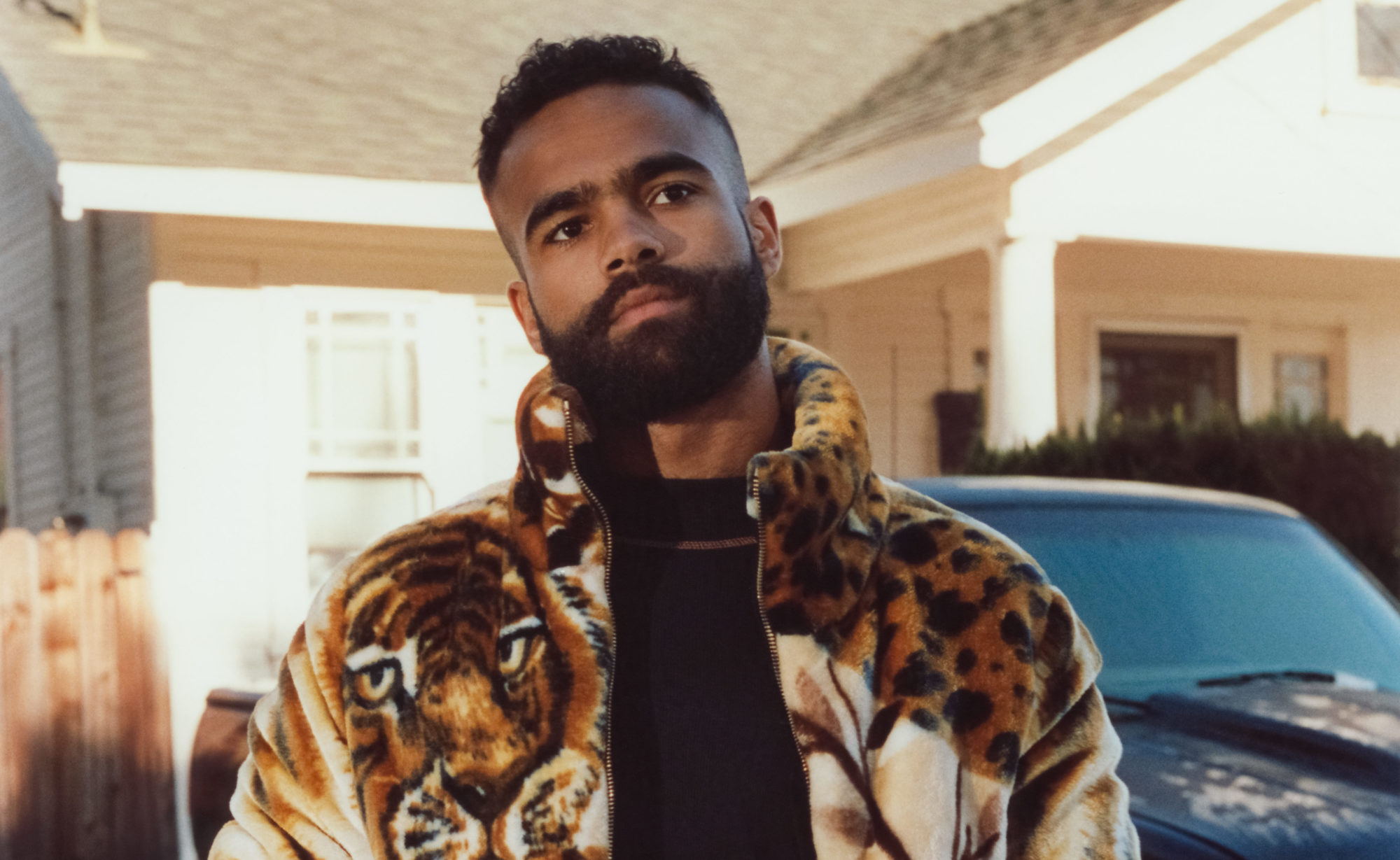

With his directorial debut Burning Cane, 20-year-old filmmaker Phillip Youmans presents a focussed dialogue on religion within black culture. Here, the Tribeca award-winning director talks about the dichotomous roles of faith and theology.

Gliding through cane fields but not able to touch them. Sensing scalding heat in the air but unable to feel it. Crickets chirp non-stop nearby, and the liquid-honey voice of a woman starts to tell a story, but she is hidden, out of sight. This is how young writer, director, and cinematographer Phillip Youmans draws us into his debut feature film, Burning Cane—by purposefully playing with our curiosity and offering a heightened sensory experience.

Youmans’ approach to filmmaking consciously confronts and questions the tropes of contemporary culture and reality. Last year, at just 19, he became the first African-American filmmaker to win the Founders Award at Tribeca. Burning Cane was especially praised for its sincerity and the manner in which it unearths the complex interpersonal relationships within rural communities. Youmans wrote and directed the film himself, as well as carrying out the cinematography—an effort that showcased not only his unbridled appetite for film but his honest desire to tell his own story.

It’s almost as if Youmans is a character within his own film. Burning Cane is an up close and personal journey through the turmoil of struggling with individual vices. Youmans has previously referred to it as a cautionary tale of the church and the institution of the church— particularly the Southern Baptist community in rural areas of his native Louisiana. Whilst not entirely criticising the notion of religion, he highlights how those who have such strong faith tend to use it as a sort of emotional shelter—a way to seek guidance and pardon. Whether it’s the alcoholic pastor who’s preaching holy sermons and completely acting to the contrary in his private life, or a God-fearing woman who tries her best to live by the Bible but has her own disingenuous exceptions from time to time, the protagonists in the film always turn back to their faith for clemency. In our current social climate, the concept of religious conviction is constantly under the spotlight. From discussions on the Church of Scientology and our understanding of reality and fiction, to using religion as an escape to abdicate certain responsibilities, the notion of belief is somewhat ambiguous. Burning Cane couldn’t have come at a better time, as many of the discussions that take place in the film comment on our understanding of human behaviour and the way we live with religion by our sides.

For Youmans, being in a constant state of controversy—between his own liberal sociopolitical views on Protestantism, homophobia, and black culture and those inherent in his familial background—led to a story teemed with introspection, tension, and tenderness. His next feature, Magnolia Bloom, tells the story of the revolutionary Black Panthers of ’70s New Orleans, and is being produced by Sundance as part of its prestigious Screenwriters Lab. Here, the promising director talks about creating a film out of high school and the contrasts that inspired his impressive debut.

You wrote and directed Burning Cane yourself, which is a huge deal considering the amount of work that goes into a process like this, but it also meant that you had full control over the outcome. What was the one thing you were really adamant on conveying?

Initially, it was always rooted around the conversation of the juxtaposing role of religion within the black community, my community. This was really the initial seed because that’s the kind of conflict and conversation I’ve been having my whole life, and it still goes on today with my family and I started diving into Negro spirituals from the ‘40s and ‘50s and listening to the Mississippi Blue Springs music. During that time, it was very focussed on the South, and that definitely influenced a lot of tonal choices for the work I was making.

The film draws on your own experiences of growing up in the American South and the role of faith and the church in your community. Did you struggle to dissect your sentiments towards religion in the film, considering your simultaneous estrangement from it?

My mom grew up in Lowcountry South Carolina in the ‘60s during a time when a very rigid interpretation of Protestantism was regularly practised amongst black families, so that entire social-political ethos was very normalised for her. I have to give her credit for not necessarily imposing that onto us. Church was the only thing she didn’t waver on, but she didn’t silence me from having disagreements, and even to this day, she is the family member that most understands the questions and separations that I have with my background. She knows I have to speak my truth.

You make a lot of powerful commentary on the restrictions and contradictions of religious fundamentalism. Was it difficult to revisit some of those moments and translate them into palpable scenes for your audience?

Yes, definitely. Though my family are very, very religious and there are a lot of things we definitely disagree on on a social and political level, there’s still a lot of love there. I have to acknowledge that religion is not divisive enough or has in any way corrupted me from spending time with them. People are imperfect. I’m done with speaking about the topic of religion and the church community in absolutes as though my word is law; however, growing up in it was a little frustrating for me because I noticed a lot of hypocrisies within the way in which we were living.

What made you feel these contradictions so strongly? Was there a moment where you realised that the pieces of the puzzle just weren’t adding up?

Some of the things we would do in the real world were completely damned in our church. There was a continual double standard and this constant stream of pretences. In tandem with this, the most difficult thing t o face was that I just couldn’t get any answers. Any question that I ever had, the only answer I got was ‘you gotta have faith.’ I feel like that’s just a shutdown excuse, because faith is such an abstract thing. This ended up making me feel super alienated from religion quite early on.

“So many things we believe because we were raised to believe them, and the idea of questioning something that you have put your whole life into is truly scary.”

How has your approach to religion changed since working on Burning Cane?

For me, it wasn’t an immediate change per se, but I’ve become much better at speaking on my differences to religion and not putting things in a black-and-white way. It’s about just being able to communicate with human beings in a respectable way, which comes with maturing. It’s an in-tandem process, and it always will be.

What did this process look like?

It’s forced me to really consider and unpack everything that goes into somebody believing in faith so strongly and the type of hope it can really give people. Although I believe that religion perpetuates a lot of traditionalist and antiquated values, shit can get hard sometimes, and having some sort of deity or something extra just helps people. I also think that there’s so much about the prison of belief that is very real.

So many things we believe are because we were raised to believe them, and the idea of questioning something that you’ve put your whole life into is truly scary. I think we need to be more empathetic to what really drives people to believe in things in the way that they do, and to recognise the fallibility of everyone.

Sometimes it seems like people use religion as a form of escapism. Our inactiveness to accept our faults and make those changes becomes a way for us to avoid our realities. Do you think this is something you were trying to convey in the character of Wendell Pierce, the troubled pastor?

Oh yes, definitely! He’s someone who is seen as this mayoral, guiding voice of the town, but clearly, he’s wrestling with some intense demons of his own. Whilst he reckons with the toxic masculinity and the blatant misogyny that gets perpetuated in those kinds of religious communities, there’s an emotional scape-goat for Pierce that he talks about—the Devil. He begins by talking about this evil brewing within man, but then, by the end of the film, he calls unto Satan as this literal evil being on which we can blame all of our own terrible wrong-doings. It may not directly be escapism, but that’s moral scapegoating, which is in the same vein of conversation—this means of avoiding your consequences.

The idea of brotherhood and sisterhood that draws through Burning Cane is quite apparent in your previous works. Is this something you felt grew out of the community of church, or was it more you finding your own chosen community to escape the strictures of a Protestant ecosystem?

That’s so interesting. I’m not actually sure why I’m driven to familial dramas and narratives. Maybe it’s partly due to the conflicting relationships I’ve had with my family and dialogues on religion. There are sometimes so many clear parallels between the things I’m working on and what’s happening in my personal life. I did a video installation once called Won’t You Celebrate With Me— that was very distinctly made with the intention of it being all about black sisterhood and these defiant black women finding comfort within one another, outside of any form of a materialistic world. I haven’t unpacked why I focus on these topics, but they just filter into everything I do.

“Any questions that I ever had, the only answer I got was, ‘you gotta have faith.’ I feel like that’s just a shutdown excuse because faith is such an abstract thing.”

You started writing the script and planning the premise for Burning Cane during your final years of high school, which is a time when individuals go through a lot of personal growth and change. How did this experience affect your process?

I completely threw my inhibitions to the wind. There was no financial pressure either, because my family and I were the only ones putting money into the film. So it wasn’t like I had to worry about answering to anyone in any capacity. The scholastic setting of it all made it feel even more like a passion project, to the point where I completely indulged in my creative instincts all the way through.

Outside of also being in high school, it was a period of change and growth for me, as I realised that if I wanted to make a career out of filmmaking, I had to take things seriously. My mentors just kept drilling into me that I needed to have patience—all of these mature realisations opened my mind into the sheer amount of time that goes into the process of filmmaking from beginning to end.

Besides hard work and endurance, what do you think is the most important factor when it comes to filmmaking, and do you hope that by putting your work out there you can inspire other young directors to do the same?

The thing I find truest and most progressive across the board is telling a story that you can really give an honest and authentic perspective on, something that you’ve experienced and lived that answers every question that you have throughout the process. You know you’re able to validate if something feels genuine, honest, and real because you know it like the back of your hand. That’s the honest truth.

Photography PALEY FAIRMAN

Styling KEYLA MARQUEZ