It was a bright cold day in April 1984. The citizens of Oceania—a joyless, war-stricken superstate—were living in a culture of fear.

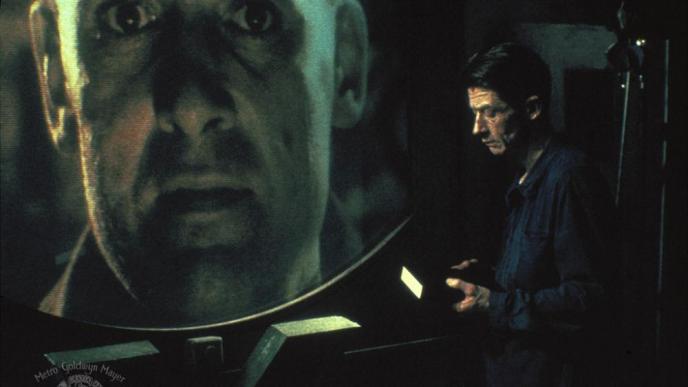

This was the world in George Orwell’s magnum opus, Nineteen Eighty-Four. Written in the 1940’s, Orwell intended to offer a glimpse at a life under Totalitarian rule. It had all the tropes of your regular dystopian novel: futuristic, nightmarish, and downright depressing. But more than anything, it was eerily prescient. In Oceania, people had a hunch that somewhere, a Big Brother was watching—you couldn’t see Big Brother, but Big Brother was watching you. Fast forward to the present and we’re living in a world surveilled 24/7 by CCTV, in a world where the term ‘Big Brother’ lends its name to one of the hundreds of reality shows that dominate mainstream television, and where we sign over our right to privacy with every set of ‘terms and conditions’ we claim to have read.

On October 8, 2019, 70 years after Orwell’s masterpiece was released, Instagram removed its “Following” feature for the sake of “simplicity”. Originally meant for users to discover other profiles through their contacts, it was a laundry list of online activity. It was pretty revealing, too. If you were on it at the right moment, chances are you could spot some pretty questionable things—whether or not someone was online (therefore confirming that they were actually not dead and indeed ghosting you), exes re-following each other, and your neighbourhood fuckboy thirst-liking 13 instamodel pics in a row.

When the app ditched the Following feed, the move was so subtle it could have gone unnoticed, if it weren’t for the thumb muscle-memory we seem to have adapted from being on the app for so long. The routine Insta app users have developed—five-or-so clicks on people’s stories, three-or-so scrolls down the homepage, a tap on the Activity feed to check notifications, and finally, if really bored, a swipe over to the right for the Following section.

With one less action from our tech-muscle-memory, thumbs the world over went ??? until we realised why.

Most of us probably threw this new fact into the backburner of our short-term memories, reprogrammed our routines—easily adapting and easily forgotten. I did too, until I, landed on a post from a radical, bra-burning feminist account. This one was mild and actually agreeable, so I let my thumbs hover over. Normally, I’d think twice about hitting “like” on certain posts, in fear that my double tap would be displayed on the feed and hung there like dirty laundry. But with the Following feed gone, no one, save for those who were also following the same account, would see if I had liked it or not. My double tap in agreement wouldn’t be translated into me being a radical bra-burning feminist. It was the power of stealth: I could like a picture. In. Peace?!

https://twitter.com/mosseri/status/1181288498654924803

It was a strange, soothing sort of anarchy—like being handed a can of spray paint, being told that I could deface any wall, then looking down at the can and not know what to do with it. It felt like unabashed free speech, something I realised I hadn’t felt in a long time.

I was born in the middle of the 1990s, thrusting me into a convenient age bracket: I experienced an entire childhood without the internet, but I also spent some of my most formative years with it. At the cusp of a tech metamorphosis, I traded my cassette players and film cameras for smartphones, and became a native in navigating them, too. But trading my analog devices for shinier gadgets also came with watching culture as I knew it transform. It baffled me—still baffles me—how an app (which, if you think about it, is a string of codes and graphics on a handheld device) has fashioned my behaviour, as well as those around me. The rules of conduct have been rewritten, and we exercise a vigilance that borders neurotic. “Don’t post that, my boss might see.” “I can’t like that, my girlfriend is going to freak.” It takes a lot of mental massaging to assure ourselves that, no, that friend-of-a-friend is not going to tell your boss. But we’re conditioned to believe that we can get “cancelled”. We’re made to believe that likes are more than what they actually are: arbitrary taps and double taps, empty reflexes as meaningless as muscle memory. We’ve operated under an Orwellian Big Brother, except ours might be more fiction than the one in the books.

Humans are curious beings by nature but it’s safe to assume that we’d be better off not knowing as much about each other. When Instagram removed the Following feature for the sake of “simplicity”, we can’t really be sure if they were referring to an interface, or a time. What is certain, though, is that it’s a step back. At this point, perhaps that’s a way of moving forward.