Cultural and economic shifts have made the concept of success increasingly fluid—but is there liberation to be found in embracing failure?

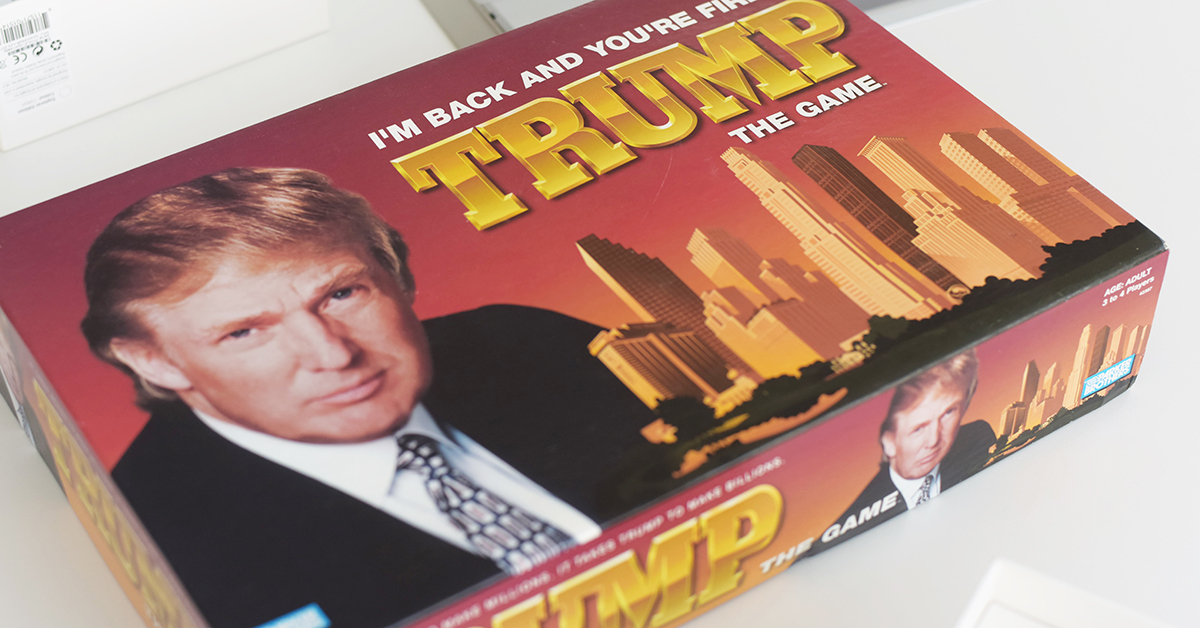

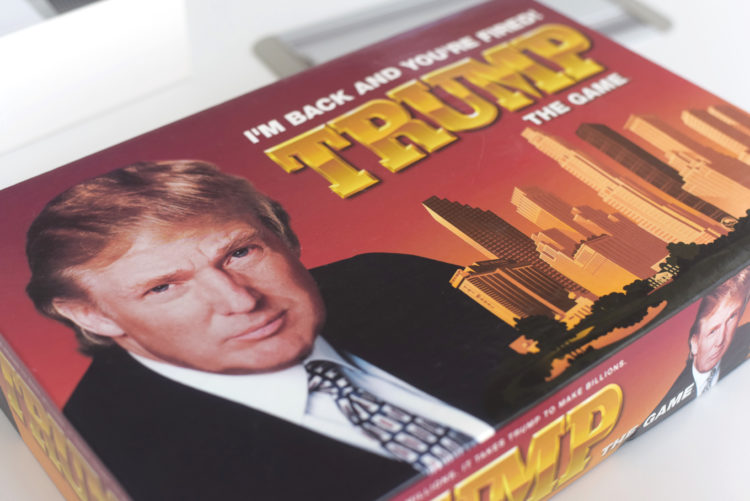

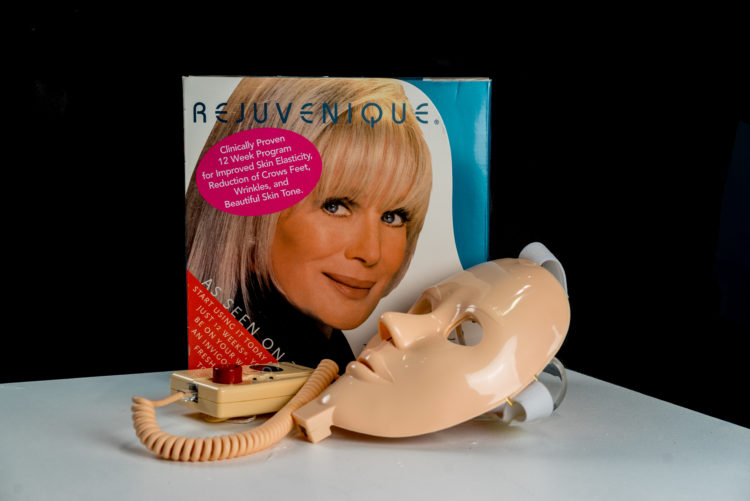

A quick Google search for words of wisdom brings up a well-heeled inspirational quote which claims: “failure is opportunity in disguise.” It’s a mantra that might seem contrived, but this pragmatic approach is exactly what lies at the heart of Sweden’s famed Museum of Failure (soon relocating to Shanghai) which houses everything from a Donald Trump board game to a series of ill-fated Coca-Cola recipes. Founded in 2017 by a frustrated Dr. Samuel West, who explains that he was “tired of reading the same success stories,” the museum celebrates the idea of learning from your mistakes without ever trying to hide them; in other words “the road to success is paved with failure.”

But what does success even mean in 2019. And how many of us actually want it? For centuries we’ve been pre-programmed to aim for marriage, stable employment and happy, healthy kids, but divorce rates have yo-yoed over the last few years and IVF advancements have made it easier than ever to beat the dreaded biological clock. As for stable employment, the Internet has blazed a trail through traditional job markets and enabled a freelance economy—one basically built on instability—to emerge and thrive.

These parameters of success are tied to heteronormativity—the societal assumption that being “normal” means being straight, monogamous and desperate to reproduce. Queer theorist Jack Halberstam (also known as Judith Halberstam) identifies this fact in his 2011 opus The Queer Art of Failure, a playful academic text which uses Chicken Run, Finding Nemo and Spongebob Squarepants as case studies. He highlights that plenty of us will naturally fall short of these benchmarks, and that we should actively embrace that failure: “if success requires so much effort, then maybe failure is easier in the long run and offers different rewards.”

There’s arguably something to be said for adopting Halberstam’s approach to a society in flux. He’s a keen advocate for embracing chaos and instability; in his eyes, success is a social construct designed to keep us in line and encourage us to monitor our behaviour at every turn. In other words, theories like these offer an alternative blueprint for life which comes with much less pressure and much more freedom. Benefits that are being increasingly identified by researchers and the creative community alike. “There’s been so much research into the future of work, and [it’s been argued] that the population doesn’t need to work five hours a week for eight hours a day,” argues artist and actor Vera Chok, who says she’s become increasingly critical of the idea of failure over the last few years. “We can dismantle these made-up rules; we don’t need to fulfil the status quo.”

For Vera, this meant working a huge variety of jobs and learning to approach life with a more critical outlook. She’s specifically questioning the idea that workers should be “productive” to be successful, a viewpoint she traces back to her childhood in Malaysia: “I grew up in a country which really pushed that idea of productivity, as we used to be a British colony and therefore needed to prove ourselves as a nation. It’s just a matter of timing and chance that Western civilisation and technology are the norm in so many places, so I think it’s a little bit sad that we tried to prove ourselves against those measures that were set in place before us. We should question those social constructs and see what works for us going forward; systems and beliefs were put in place to keep people in place.”

It might be liberating to follow this approach and redefine success on your own terms, but reprogramming attitudes can be more difficult than it sounds. London-based writer Katie Muxworthy, who says she has long struggled to come to terms with the idea of failing, explains that she still thinks of failure as something automatically negative, but that she’s learned to put less pressure on herself over the years. “I associate failure with not doing something I set out to do, but now if I do feel like I’ve failed I just try to be kinder to myself and not attach guilt to it. That’s come from practice—and I even fail at that, too!”

Like many other millennials, Muxworthy has learned to place value on the things she deems important rather than jumping through the career, marriage, house and kids hoops. “I’ve watched my peers—younger and older—hit ‘life milestones’ at different ages, so that made me reevaluate what I should do with my life. Now I think success can mean lots of different things—to me it’s about maintaining a healthy relationship with myself, about being as healthy as my body allows me to be and about working hard enough that I can pay to do the things I enjoy.”

This idea of building a healthy relationship with ourselves is more important than ever. Mental health problems are worryingly prevalent amongst millennials—an issue which has been blamed on everything from social media to economic instability—and articles consistently highlight that we’re financially screwed, which doesn’t exactly help. Capitalism is strengthening its vice grip on the world, and young people—often overworked and underpaid—are particularly vulnerable to its effects.

Millennials might be berated as lazy and entitled, but the truth is that for those of us struggling with mental illness, success can literally mean survival. “I tried to take my own life several times because of bullying in school,” says Freddie Cocker, a survivor who channelled his own experiences into the creation of Vent, an online platform that houses the unfiltered stories of people struggling with mental health problems. “Making it to my sixteenth birthday was a success for me—even that was something I didn’t think I’d be able to do.”

Now Cocker is a comms professional with a passion for advocacy; by sharing his own story and encouraging other men in particular to open up about their struggles, he’s counteracting a lack of social media transparency that can lead us to believe we’re failing in comparison to our peers. “The goalposts have now shifted for me,” he explains. “Success still means survival, but it’s also tied to the amount of people I’ve helped and my own ability to recognise my flaws and try to improve myself.” By redefining success on his own terms he’s learned to prioritise his mental health and not punish himself for reaching conventional milestones, a tendency even the most carefree among us can be susceptible to. “Success is whatever our definition of it is; it’s something which should ultimately make us happy,” he says.

This attitude seems to be more prevalent than ever. The last few decades have seen house prices rise, tuition fees soar and businesses take advantage of a job market which has normalised instability and a lack of workers’ rights. Attitudes towards sexuality have also shifted; fewer people identify as “straight” than ever before, with more of us embracing a fluid approach that challenges the idea of any “normal” sexuality. As a result, marriage is deemed to have dropped down the priority list for plenty of people—and in all probability, most of us just can’t afford it.

The societal goalposts we’ve long associated with success—marriage, kids and stable employment—are also becoming more difficult to achieve. And if the Museum of Failure can teach us anything, it’s to embrace our mistakes and acknowledge that failure, too, is a social construct. Whether we aim survival, self-care to live in the moment in the moment, there’s a lot to be said for deconstructing the idea of success and rebuilding it on our own terms; why battle against the tide when we could just accept that we’re all, in some way, doomed to fail?

The Museum of Failure was established in Sweden in June 2017 by curator and psychologist Dr Samuel West. It is home to a vast array of failed products and services from every corner of the globe. West aims to showcase the risks that surround innovation and to push creators into learning how to make more meaningful projects. The museum now has two new locations one in Munich, Germany and the other in Shanghai, China.

All photos by JAKE AHLES

Header image by SOFIE LINDBERG