Dutch-Vietnamese silversmith Nhật-Vũ Đặng injects his jewellery with playful mischief. Grounded by the aesthetic comfort of Scholl shoes, his hands are guided by instinct, precision, and the quiet ritual of craft.

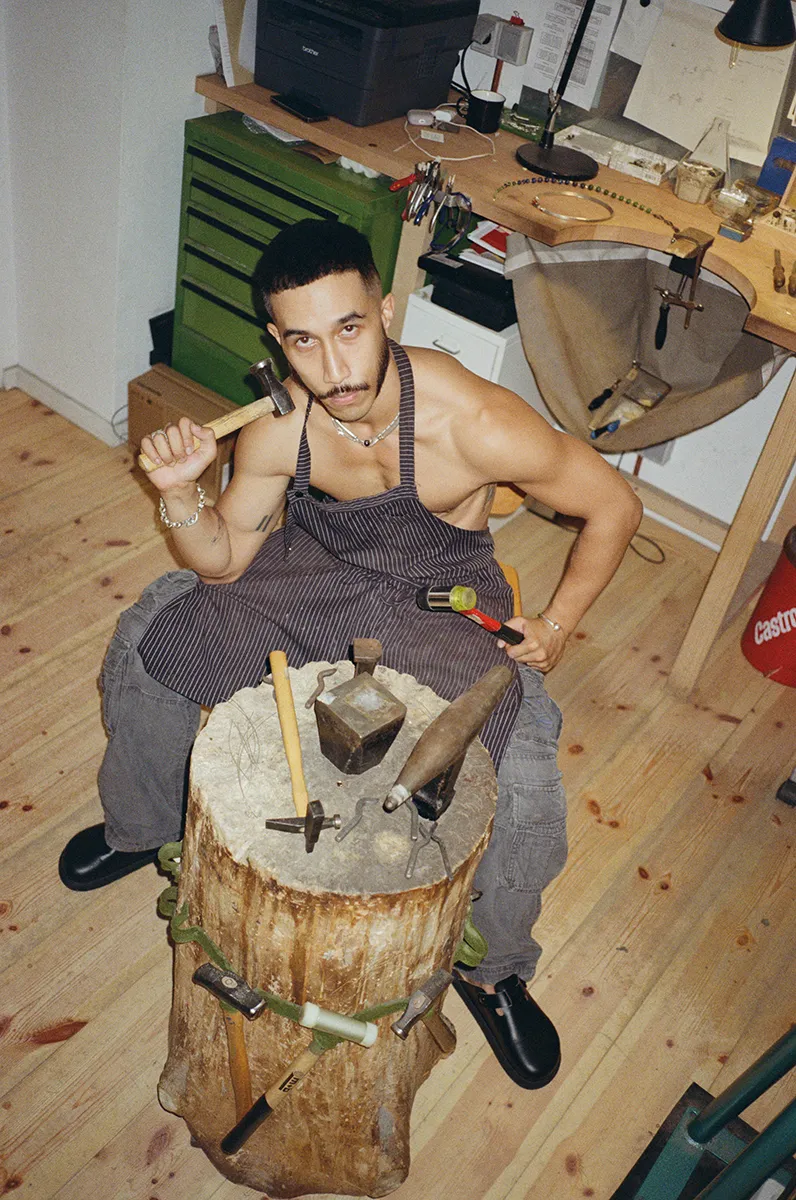

An eye-shaped spiral clings onto a lapis bead that stares right back. A svelte silver hand slips into a gold mouth, thumb hooked at the lip. For jewellery maker Nhật-Vũ Đặng, the clasp is never an afterthought. His closures don’t just fasten—they glare and flirt with being the centrepiece. “If I see a piece of jewellery where the clasp is innovative, I immediately want to buy it,” he says with excitement on a Sunday afternoon at his Berlin studio, a space he shares with four other jewellers. He’s dressed for the workbench: a khaki tee, grey cargos, Scholl mules, a workshop apron, and one of his own chokers snug around his neck.

On said choker is one of his most recognisable closures, the Eyelock. When it debuted on GmbH’s AW22 runway, a model strutted down in a black coat with an exaggerated, sculptural collar, its open back framing a silver necklace strung with gold-plated brass charms. At its centre was the Eyelock clasp, with a chain of lapis lazuli beads dangling from the middle. It has since become his signature hardware. The eye, Đặng recounts, came to him at the threshold between waking and sleep. In the vision, he saw a universe in which the one singular being was an eye. All alone, the eye questioned itself and shed a tear—a single drop that birthed good and evil. “Good arrived with a sense of guilt,” Đặng explains. “What had it done to deserve being good? Evil arrived with jealousy—what had it done to deserve being evil?” Both realised that these feelings would lose their weight if they could become one with the source: the eye.

Clothing NHAT’S OWN Shoes SCHOLL

This story is not a one-off. Đặng’s practice arises from grappling with polarities—East and West, fashion and art, creativity and commerce—and the ways these forces intermingle and transform each other. His 2018 Where the Hell Are My Keys?! collection, shown at Galerie Rob Koudijs, fused Vietnamese and Dutch references into sterling replicas of ceramic shards etched with respective cultural motifs. Between 2020 and 2023, Đặng collaborated with GmbH on showpieces for four collections, thrusting his jewellery into the fashion industry. This period challenged him to reimagine how his work could be wearable, in the process expanding what jewellery itself can be. Ethereal yet ancient, with a subversive playfulness, his pieces have found their way beyond galleries or runways, adorning artists and DJs the likes of LSDXOXO, MJ Harper, and Kim Ann Foxmann.

Born in Hoorn, the Dutch port city where his parents settled after fleeing Vietnam in the 1980s, Đặng grew up in a household of “gifted hands.” His mother was a seamstress, his father an engineer (specialising in machine parts for candy-making,) and three of his four siblings became dentists. Đặng was admitted into dental school but secretly applied to Amsterdam’s prestigious Gerrit Rietveld Academie. Once accepted, there was no looking back. In 2012, Đặng moved to Berlin and launched his eponymous jewellery line. For a decade, he juggled gallery shows while climbing the ranks at Comme des Garçons—from sales assistant to buyer—before devoting himself wholly to his craft.

Early works were concept-driven and became a way of metabolising aspects of his life, like coming out queer, and mapping his Vietnamese-Dutch heritage. Making jewellery transformed rupture into objects that were tactile and enchanting, with a touch of playful mischief. “I had to process a lot of these themes so I could be free and work how I do now,” he candidly declares. “I’ve done that work and I don’t want to be weighed down by it anymore.” For him, heritage and identity aren’t animating themes—they’re the biography he was born into and the context in which he makes jewellery.

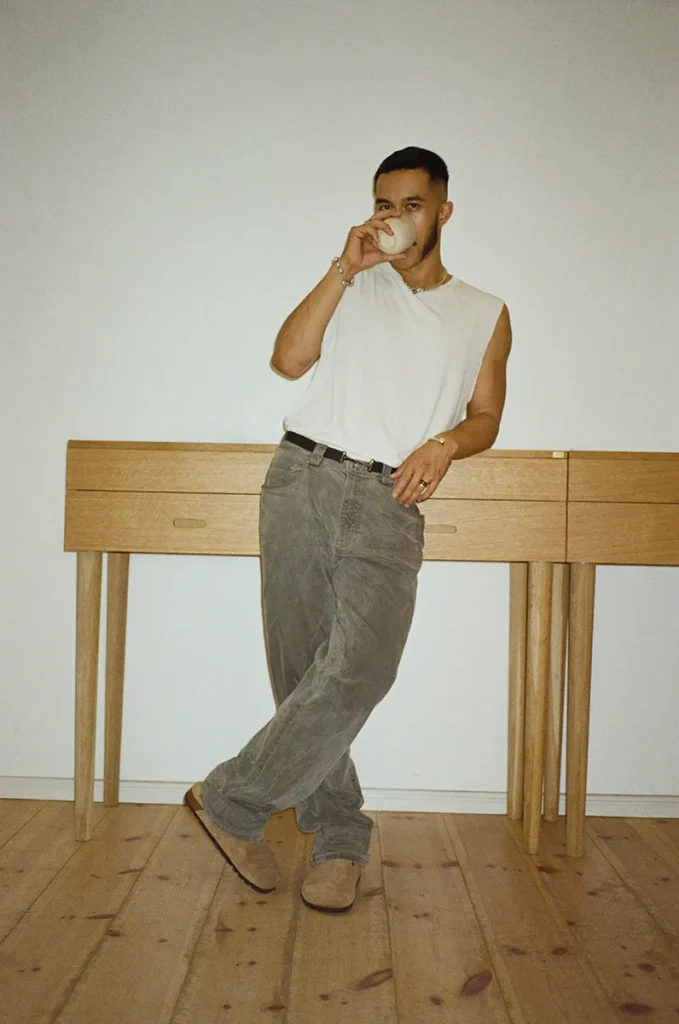

Clothing NHAT’S OWN Shoes SCHOLL

Đặng now has studios in Berlin and Hanoi, where his boyfriend also runs the club Savage. He works less from concepts and sketches than from instinct, often beginning with raw materials gathered from his travels across Asia—jade, abalone shells, black-purple pearls—and letting ideas take shape in his hands. Each piece is moulded by play, process, and the subconscious, tested against gravity, fit, and texture. “Sometimes the final piece isn’t what you had in mind, but the process leads you somewhere unexpected—creating a piece that’s great in its own way,” he explains. The silversmith sees constraints and accidents not as setbacks but as bridges to new methods of working. This openness flows into the pieces themselves, which are often adjustable and invite wearers to interpret them on their own terms. Take the Larvae charm: a string of semi-precious stones in a gradient of sizes and colours with a steel karabiner. It can be worn as a bracelet, anklet, keychain–or hung from a cap.

“There’s magic in jewellery,” Đặng insists. “It’s intimate—it touches the body, carries energy, and can hold power. When I make something myself, I set an intention for it. I imagine who will wear it, how it will move on their body. I believe all of that goes into the piece.” That insistence on intimacy resists the logic of scale. “People always tell me to go retail, to outsource to a factory,” he says. “But for now, making a piece of jewellery with my own hands means I can set an intention.” Only the casting is outsourced, a move to dodge fire hazards and toxic fumes that require an industrial set-up. The refusal is not about nostalgia for craft but about keeping objects charged. Jewellery without a hand in its making, he suggests, runs the risk of inertia.

Paid partnership with Scholl