Feasting on the nostalgia of Chantal Regnault’s intimate photographs, Mikelle Street serenades the birth, power and magic of ballroom’s ready-made muses.

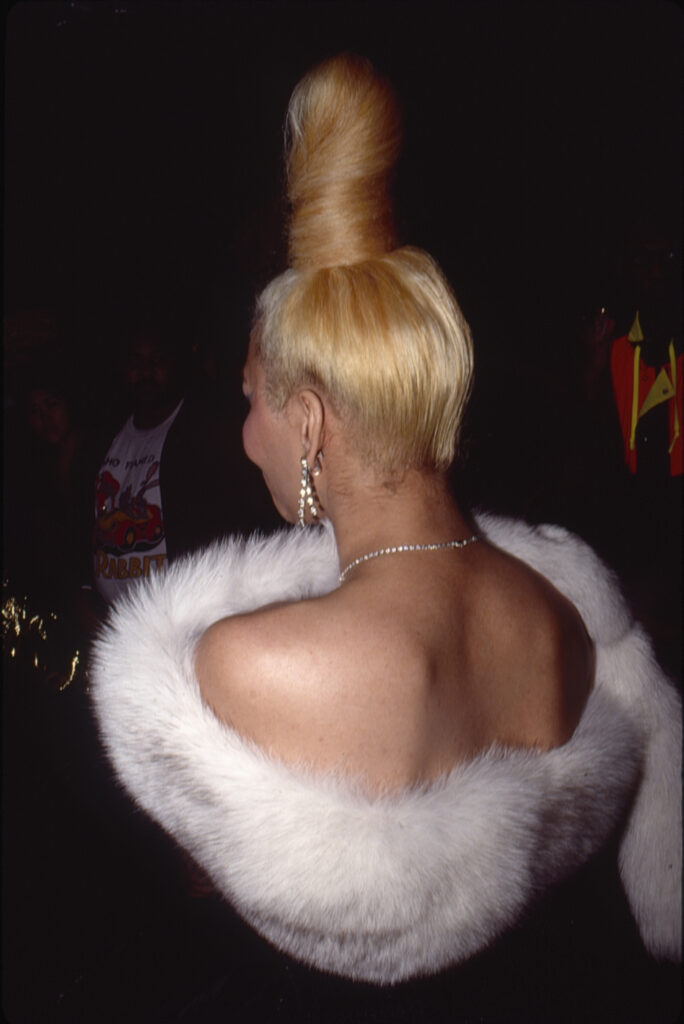

No matter the era, one of the first things you notice about a ball is the music. Step into a function in the ‘80s or early ‘90s, and it’s a trance-inducing mix of house and disco. A type of body-music that makes you want to move, that puts what some call a “Jones in the bones.” That soundtrack is punctuated by yells, screams, foot pounding, chanting and clapping. A voice on the mic, often sharp, cuts through it all, wrestling control of the building’s attention, calling out both categories and contestants. Octavia St. Laurent appears at the back of the runway, after cutting through the crowd with command. She wears a sleek black dress—shoulders adorned with shimmering crystals and a luxurious fur draped over one side. Her hair is impeccably coiffed, her red lips precisely painted. There she stands—a legend. A picture of elegance and poise.

“It was magical,” says photographer Chantal Regnault, who attended her first ball in April 1989— thrown by the House of Ultra Omni at New York City’s now-shuttered Tracks club on 19th street in Manhattan. “I was completely absorbed, knowing immediately that I would go to more balls.”

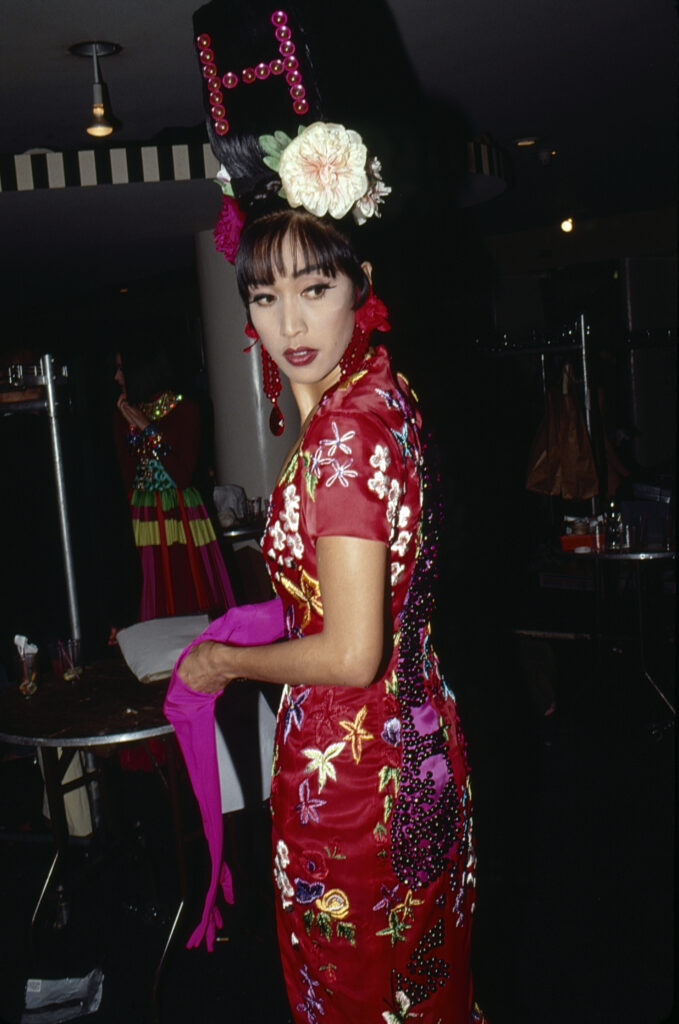

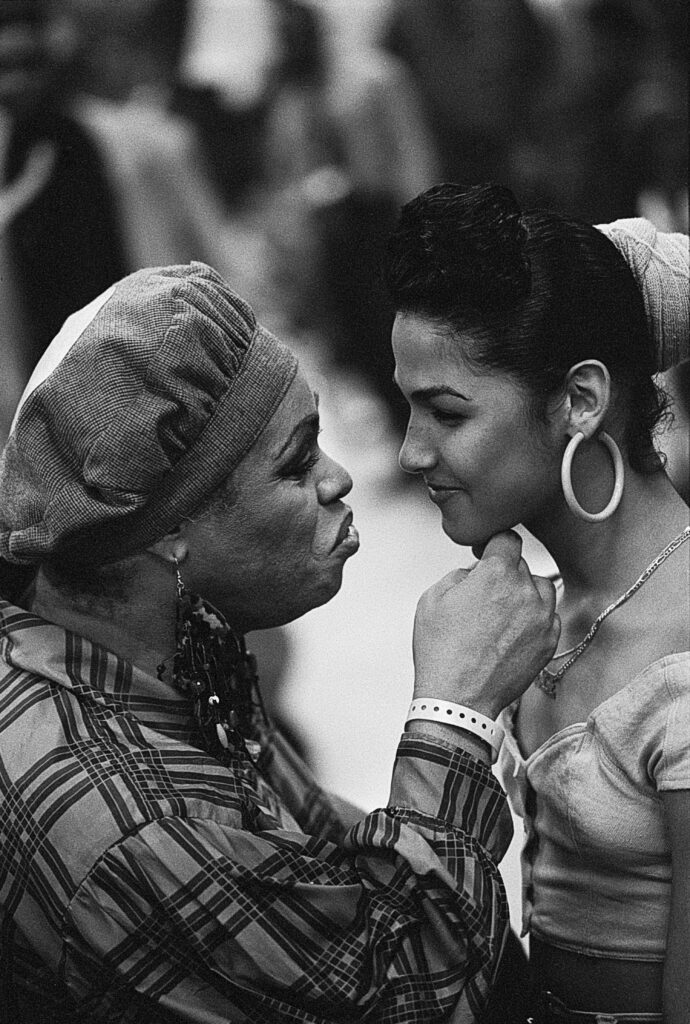

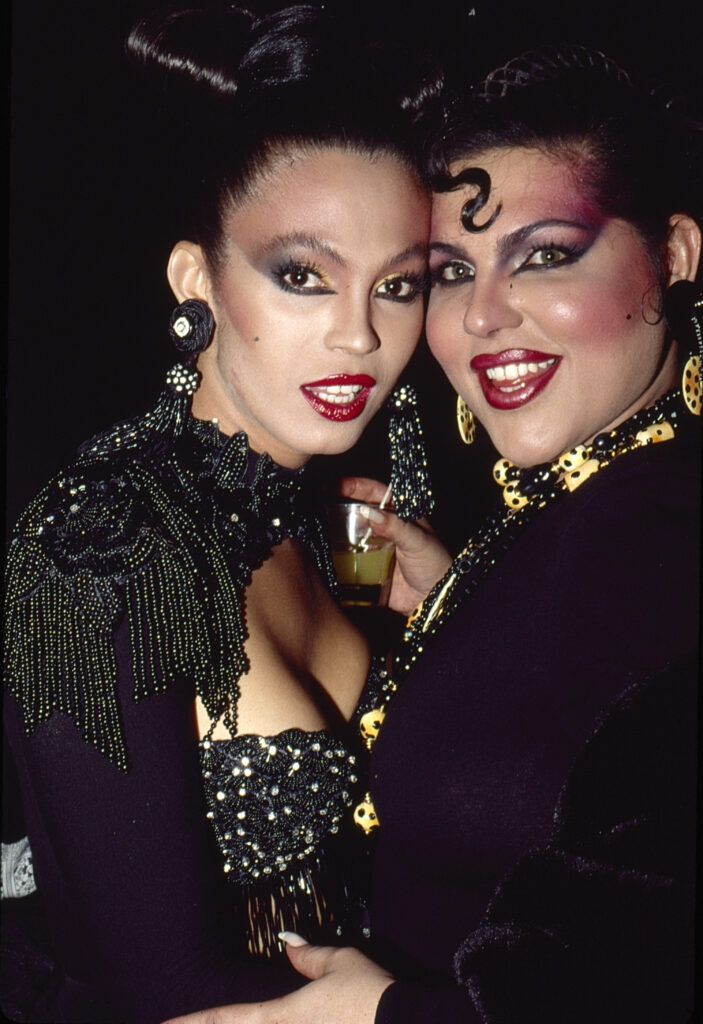

Carmen Xtravaganza and Lady Kateria Continental

at House of La Beija Ball #3, Kilimanjaro, September 1990

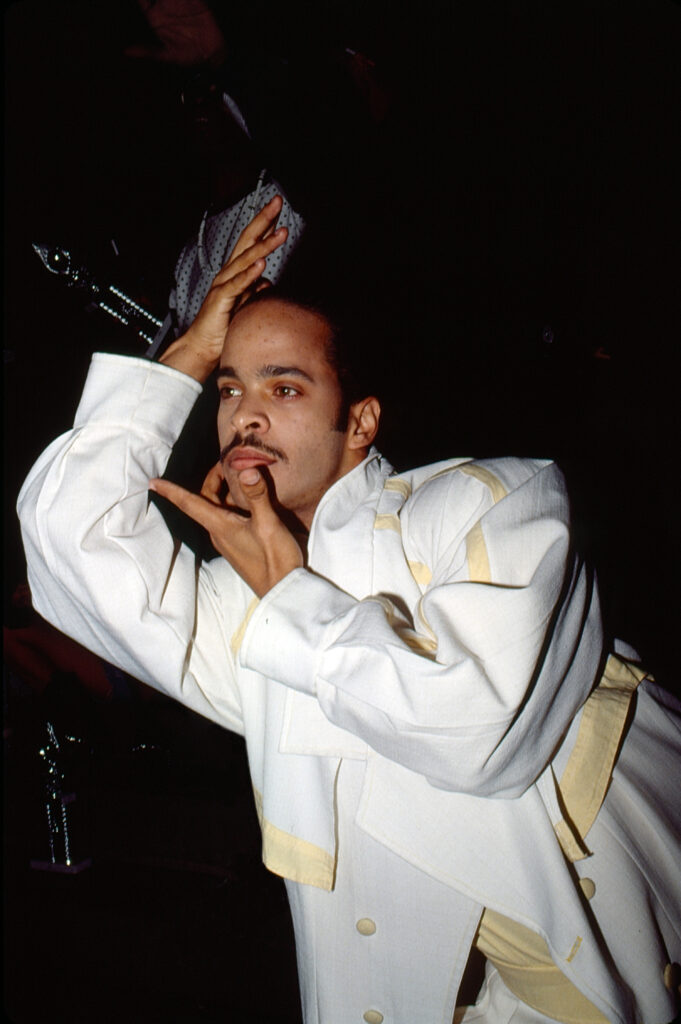

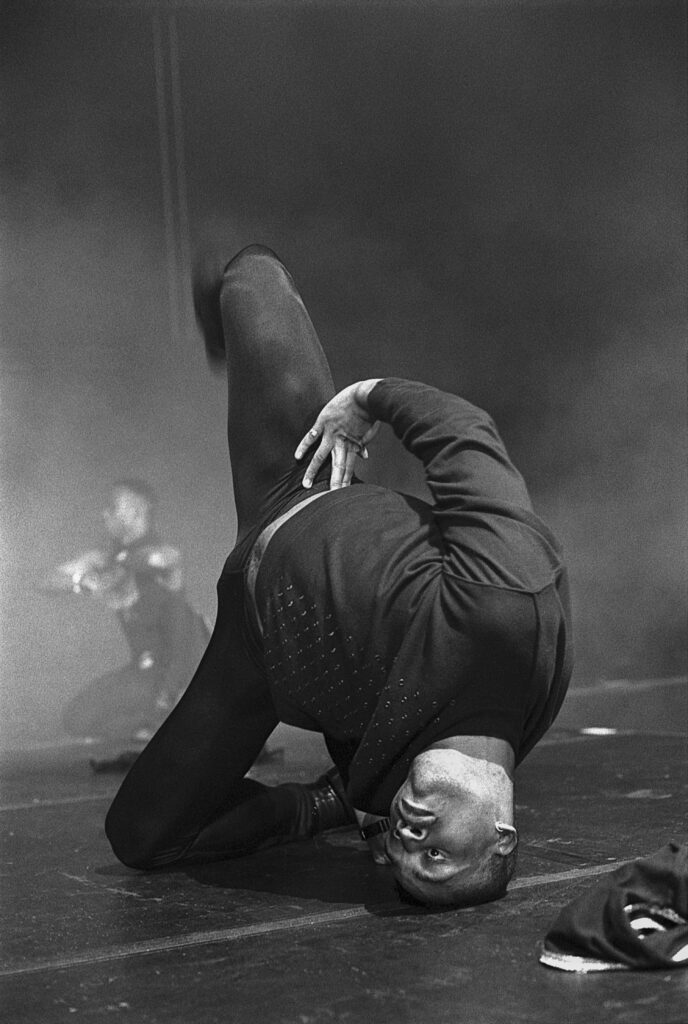

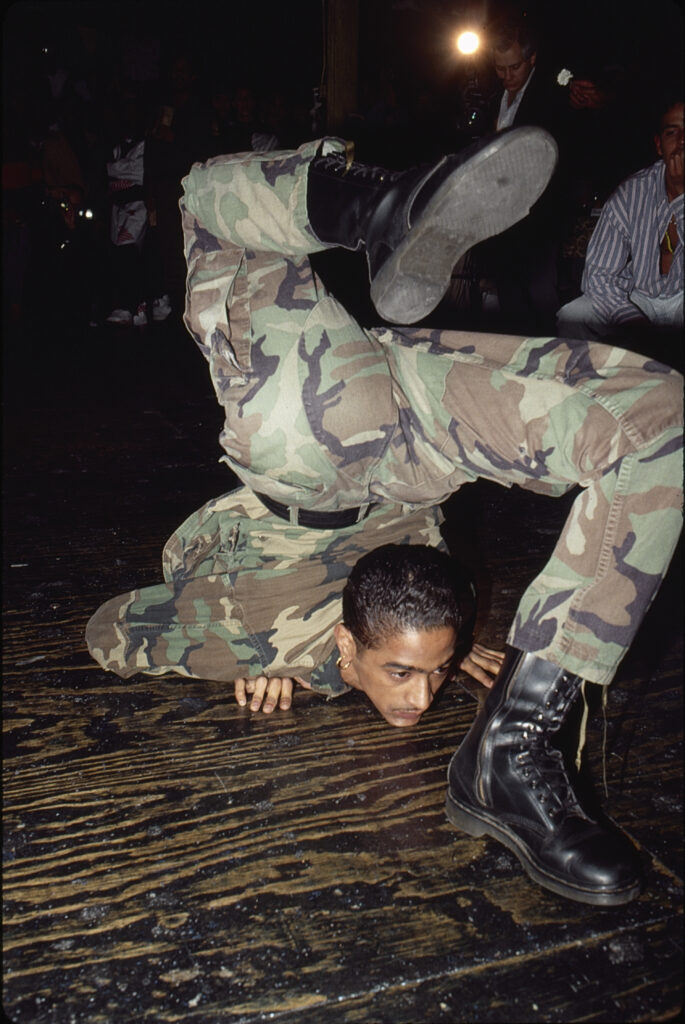

Jose Xtravaganza at David Ian Xtravaganza and Roger Milan‘s ‘War Ball‘, Sound Factory, April 1991

Balls are a cornerstone of the house-ballroom community that launched in 1970s Harlem. A descendent and splintering off from America’s history of drag balls, which dates back to the 1800s, the ballroom scene was founded as a space of refuge and community for largely Black and brown LGBTQ+ folks. It is widely viewed as a reaction to the racist reception that Black queens were experiencing on the drag ball circuit, a parallel to the culture of hip hop, which started at the same time in the Bronx, and an eventual reaction to the abysmal state of social services and care in New York City. Community members organised themselves into surrogate families with their own names (often pulled from high fashion houses or the names of the scene’s founding mothers who had started their legacies in the drag ball circuit) to share knowledge and resources as well as compete as teams in categories at balls. And it was in these spaces, their own safe places, that they fashioned the world anew, creating their own language, dance style and more in cultural productions that have inspired the world over the span of five decades.

The walkers of ballroom’s floors have served as ready-made muses. They have inspired global popstars: from the sharp lines of Madonna’s 1990 Blond Ambition Tour to the divine femininity that served as the driving force of Beyoncé’s 2024 Renaissance World Tour. After a landmark Village Voice May 1988 article, the scene captured the attention of videographers like Jennie Livingston who would go on to make the film Paris Is Burning as well as Regnault, a French photographer who was living in New York and looking for stories to tell. Many of those stories were fuelled by the magic of balls.

“During the seven or nine hours we were at a ball, it was a fantasy,” explains Michael Roberson, a theologian and historian of the ballroom community. “We were able to fantasise that we lived in a world that allowed us to unapologetically be who we wanted.”

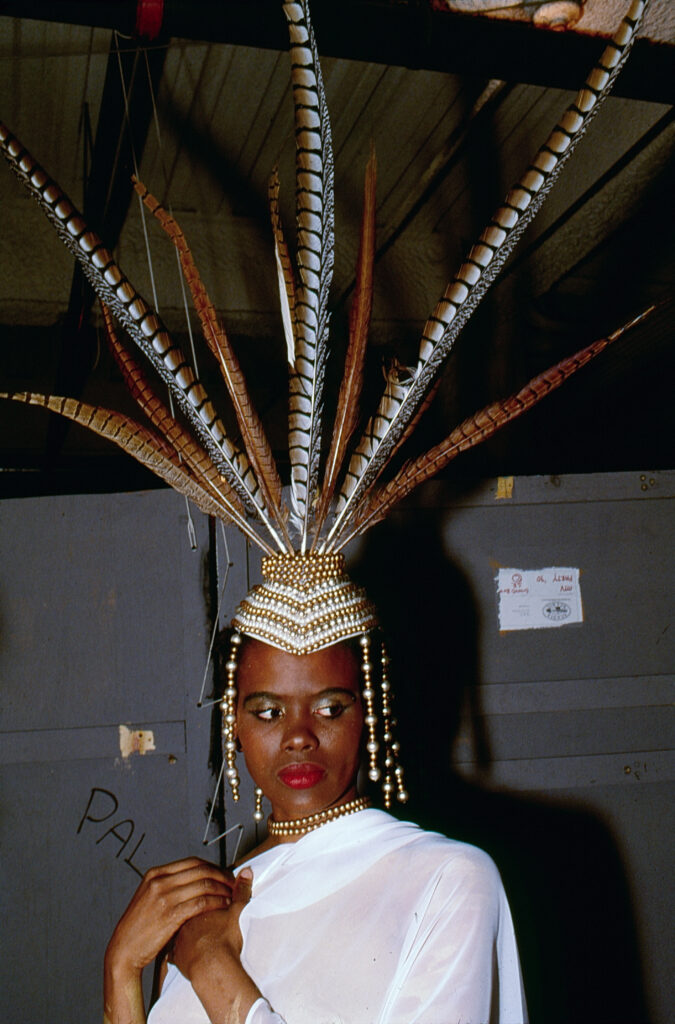

Modavia Labeija, W. 30th Street, December 1990

Smiley Pendavis at the Love Ball #1 AIDS Benefit, Roseland, May 1989

Regnault’s images of the ballroom scene and its affiliated community—almost all shot in Manhattan between 1989 and 1992—encompass some of the most referenced and revered photography of the scene. They appear not only in her book, Voguing and the House Ballroom Scene of New York, but in travelling exhibitions, a digital archive of the community from Google and more. From intimate moments between members of the House of Saint Laurent on the sidewalks of Harlem, to candids of people like a smiling Carmen Xtravaganza—who graced the cover of that 1988 Village Voice issue—as well as studio sittings, Regnault captured it all. But some of the most circulated are her high glam, reportage-style images of the balls themselves—images that helped to further the community’s influence.

“There’s something so heartfelt when I look at images from that time,” says Iman Hill, a member of the community who was inspired, in part by Regnault, to create her own documentary imagery and footage. “For me, it’s something so tangible. Any time I look at Chantal’s images, I can feel the moment she took the photo.”

Those moments were precious—a sanctuary carved out during what could often be a dire, unaccepting time for the queer and trans community, particularly Black and brown folks. As Roberson notes, in the ‘80s and ‘90s, those who dressed for the balls often couldn’t safely walk through their own neighbourhoods in the outfits they had showcased on stage, for fear of violence. In 1990, the New York Times reported a surge in attacks fuelled by homophobia and HIV stigma, citing 316 bias-motivated incidents— surpassing the previous year’s figures. As a result, many would change at the ball or in nearby public restrooms. And if they left the venue fully done-up, in the early light of Sunday morning, they could be met with looks of disdain, or even eggs and water balloons to the face.

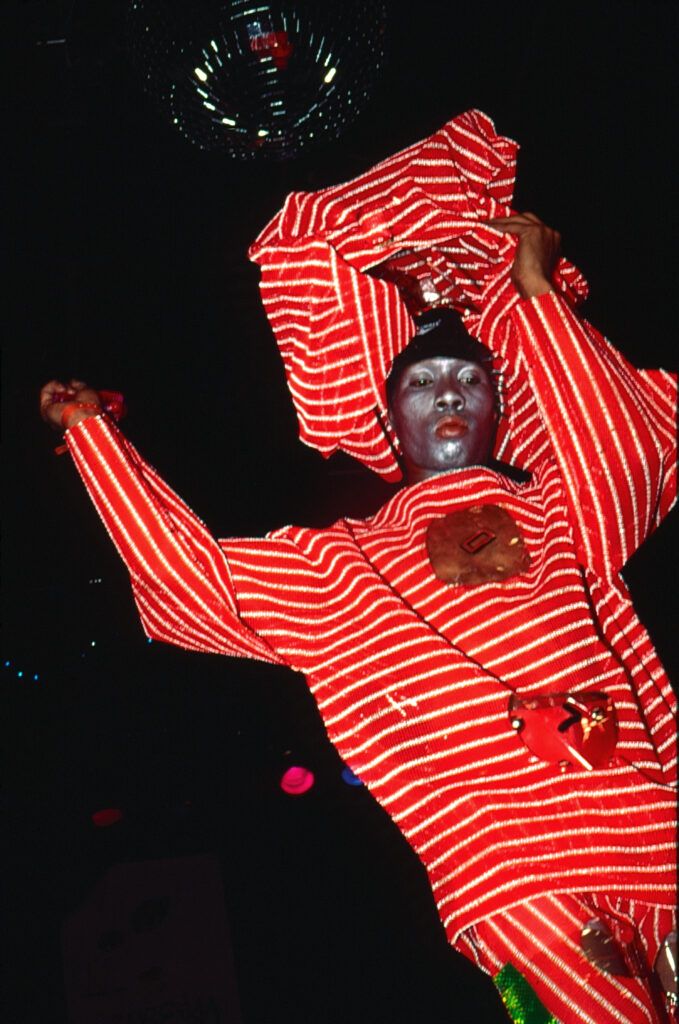

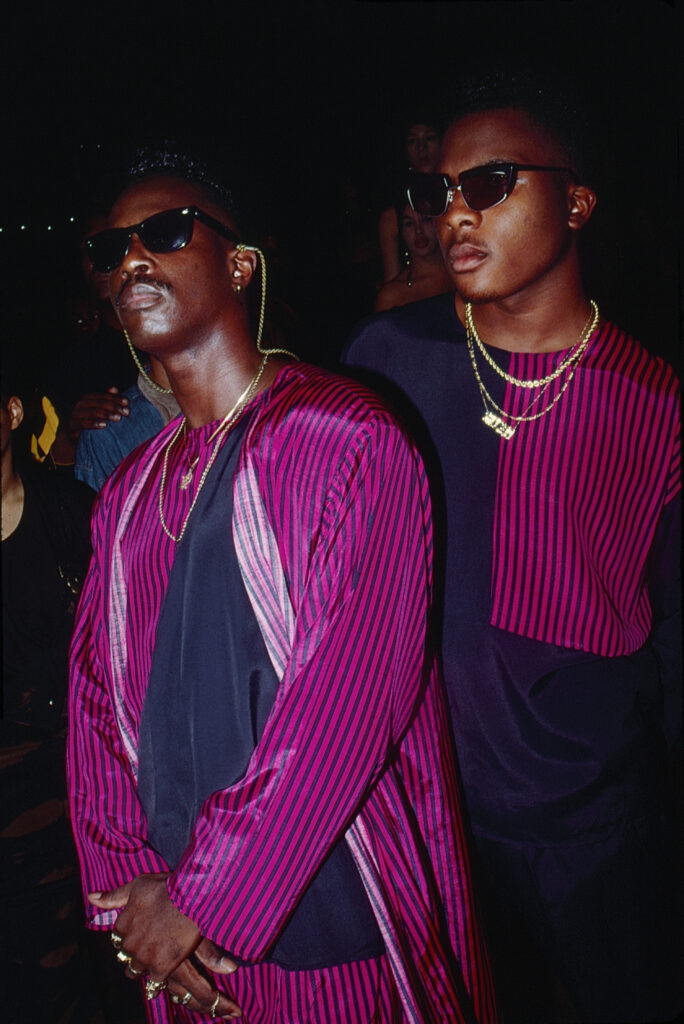

House of Ultra Omni Ball #2, Red Zone, October 1990

House of Ultra Omni Ball #2, Red Zone, October 1990

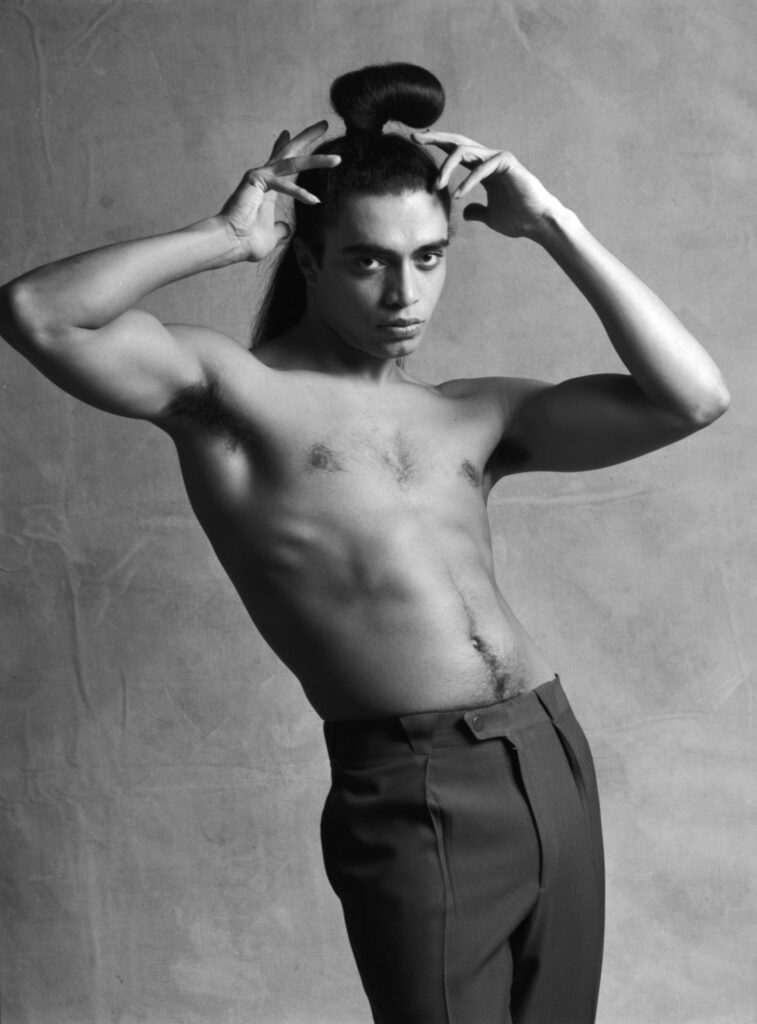

“In the ballroom world, you could express yourself in a way that was different than in the Bronx, where I’m from,” says Adrian Alicea who notably made history in 1989 with Willi Ninja, performing on the runway for five Thierry Mugler fashion shows before later filming the music video for ‘Deep In Vogue’ by Malcolm McClaren. “I remember Willi telling me he used to put a razor blade under his tongue because he would have to fight people on the train coming from Queens—they would pick on him.”

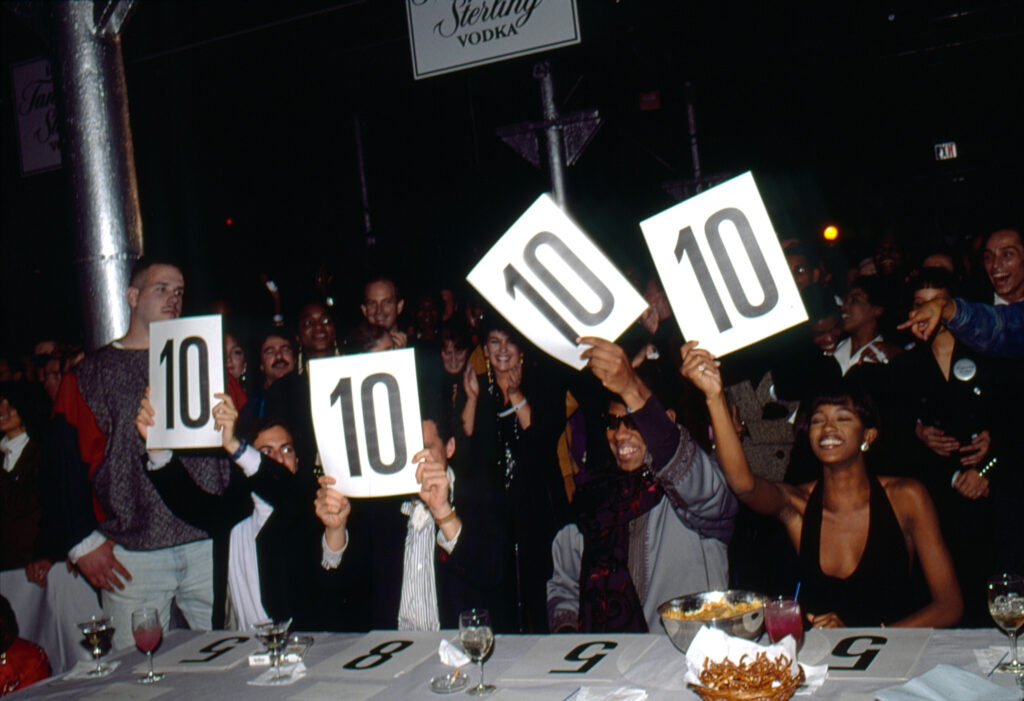

And so, the ballroom scene not only provided spaces for people to be themselves, but be celebrated and applauded for it. In addition to trophies and cash prizes, the most talented and dedicated performers earned stature and cultural cachet within the community. These functions became the venues to convene and be seen, irrespective of the increasing presence of cameras.

“It was our Golden Globes, it was our Emmys,” says Benny Ninja, who after making his name in the scene, logged time as an America’s Next Top Model posing coach—working with Tyra Banks from 2007 until 2009. “In order to be involved, people got dressed up. I can’t say that we were doing it specifically for the camera or a video recorder, but to us every eye was a camera, and every eye was a judge.”

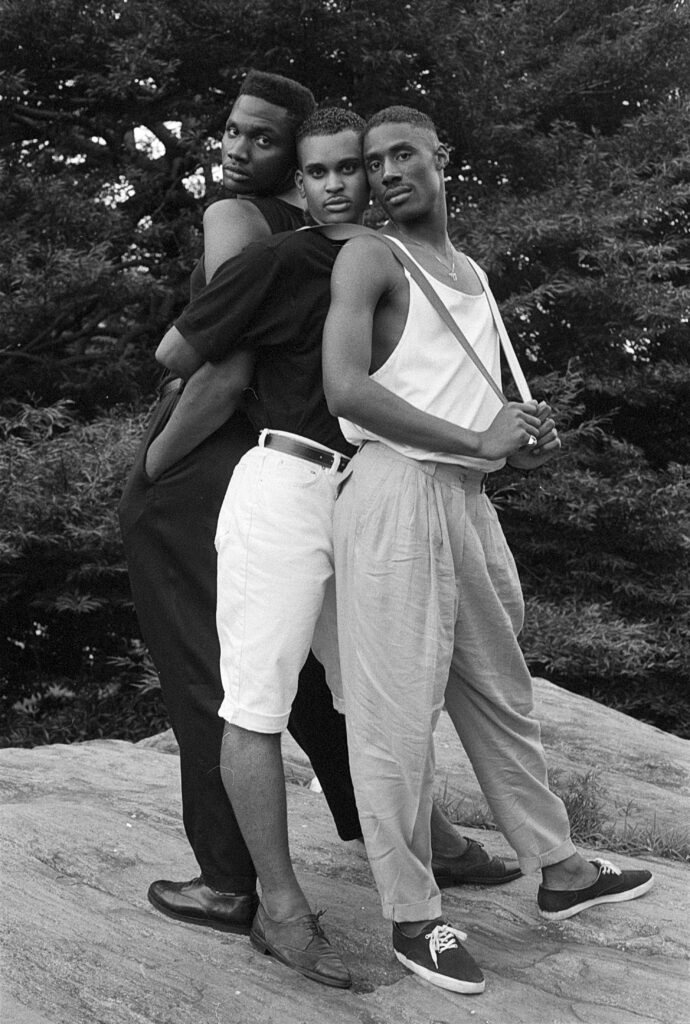

Tracey and Kevin Afrika at the House of La Beija Ball #2 (Francisco and Akiem), Brooklyn, March 1990

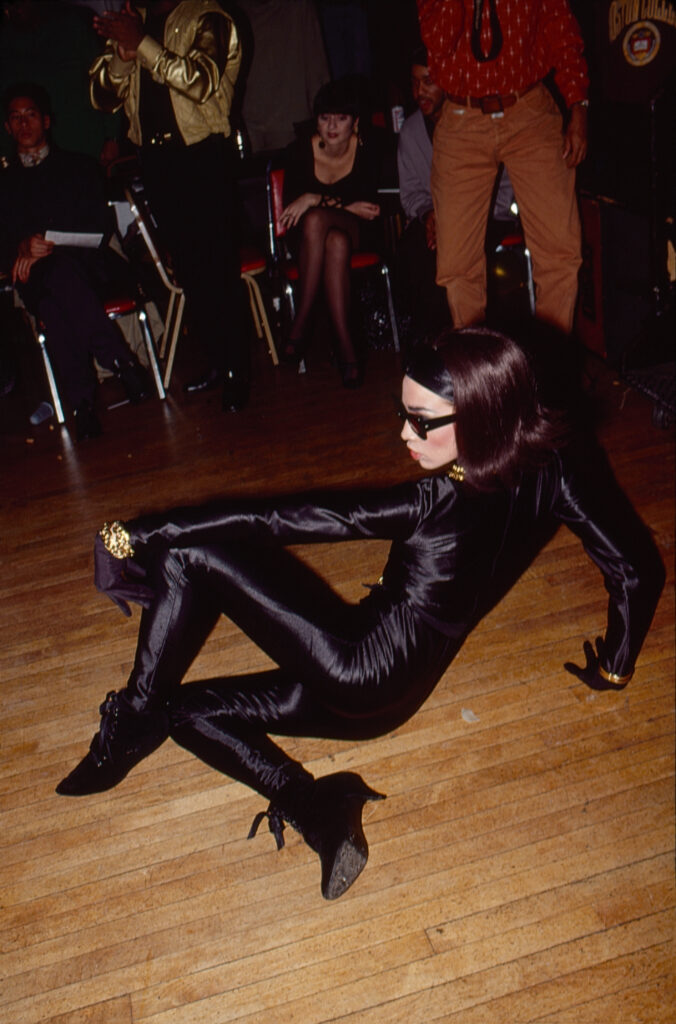

But balls allowed for more than just authenticity, and the freedom to be oneself. The ballroom floor permitted attendees to reform themselves, if only for a night, into the figments of their own imagination. Often the product of previously unappreciated skills, alter egos were crafted and presented with a type of ostentatious and arresting beauty—the sort of visual that is not at home in the every day, but finds its way onto moodboards and in reference collections.

“What you all see is the finished product of the imagination, or as Octavia St. Laurent might say, the finished product of the illusion,” Hill says. “There’s a difference between what we show and who we actually are. And a lot of times what we show is who we actually wish we could be on a more consistent basis, but might be quite far from who we are.”

While many photographers sought and still seek to reveal and unravel that illusion, and dismantle it in favour of a presumed “true self,” Regnault dared to not only emphasise it, but immortalise it. On the catwalk, she prized capturing Tracey Africa Norman as the pinnacle of glamour, and Jose Xtravaganza’s physical contortions for all of their physical ingenuity. “I wanted to show them the way they wanted to be seen because they already had this talent,” she says. “They were the artists: so much incredible talent deployed by people who often had very little training.”

Marc Jacobs, Isaac Mizrahi, André Leon Talley and Naomi Campbell at the Tanqueray Ball AIDS Benefit, Sound Factory, November 1989

But that body of work did not come without critiques. Whether levelled at Regnault specifically, or at other photographers who were not a part of the community more generally, many have questioned not only the gaze (outsiders can take an exoticised or fetishistic approach) but also who benefits from such imagery and footage. Images owned by those outside of the ballroom scene will often end up inspiring people even further removed from the scene—who can turn that inspiration into personal monetary profits.

“This debate was quite needed and necessary,” Regnault reflects. “It is good that documentary photography has to question its own approach, especially when the subjects are [people from other cultures, countries etc.] But the outsider’s look is not necessarily predatory, and can originate in a feeling of closeness and natural alliance.”

Some members of the community appreciate Regnault’s work as a result of both the reverence and intimacy depicted. More importantly, these fleeting moments were preserved for posterity. The archiving of these precious events, crystallised in an era when the community battled the twin epidemics of AIDS and crack, as well as hate-fuelled violence, make the depictions all the more vital.

Willi Ninja, E. 23rd Street, June 1989

“I have no issues with a woman who used her access and resources to uplift this community when no one did,” Hill says, pointing out that Regnault was taking images before the ballroom hysteria of the early ‘90s caused by Madonna and Paris Is Burning. “Not everybody had the means to a camera back then and not everybody had access to get photos printed. So much mental capacity was spent on just existing as a Black trans woman in the ‘80s—who would say let me go pick up a film camera to remember this moment? But we have these moments because Chantal did. For that, I’ll give grace.”

Those captures have served as a record of lives lived and liberation that was fought for. The unbridled creativity and panache depicted have inspired culture and industry the world over. But, possibly more importantly, these images and their muses have also served as beacons of possibility for younger generations of queer and trans people. The archive serves as a visual reminder of what they are capable of, because like-minded spiritual elders have done it before them.

“[These images] have allowed for people who are maybe two or three times removed to feel like they have access to ballroom,” Roberson says. “And that has been helpful.”

Mikelle Street is a Manhattan-based freelance writer. Ballroom: A History, A Movement, A Celebration—a book of history on the scene by Michael Roberson with Mikelle Street, is forthcoming next summer.