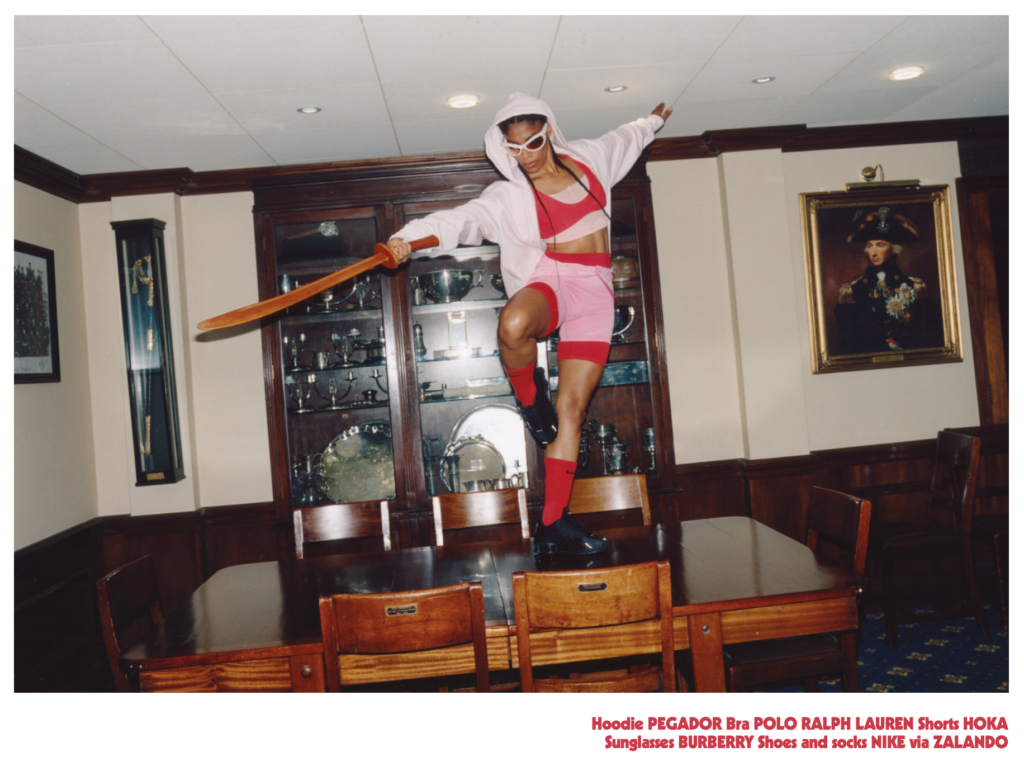

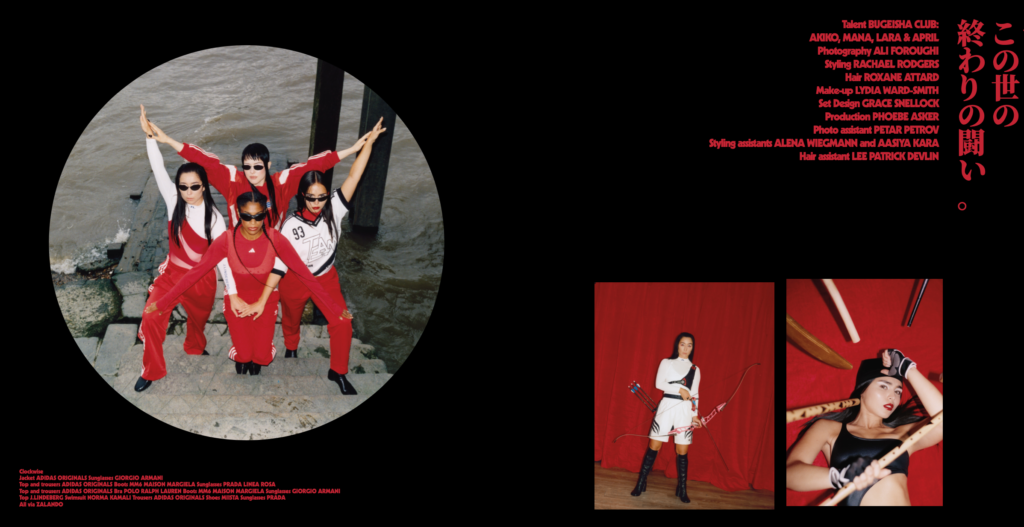

Bugeisha Club is bringing nunchuck royalty, bewitching broadswordery, and a sci-fi sense of streetwear style to the world’s end. In London, Ali Foroughi lensed four of the collective’s valiant vigilantes, styled in streetwear available via Zalando.

Somewhere between Akira and Soulcalibur, between Takashi Miike’s hyperviolence and Hayao Miyazaki’s moral complexity, a group of women in London are preparing for the end of the world. Together, they make up Bugeisha Club, the amateur martial arts collective blending broadswords, butterfly knives, contortion, and creativity to give shape to an alternate reality where its members—and other women like them—obliterate the apocalypse.

Bugeisha Club takes its name from the Onna-bugeisha, a class of female samurai whose feats pepper the Japanese historical record as far back as the twelfth century. Their signature weapon was the naginata, a single-edged polearm (somewhat like a spear), and they fought fiercely in defensive combat. These warriors battled and strategised with prowess and precision, defying the dominant Western narrative of samurai warrior culture as an exclusively male domain. “They were called upon in times of need when the men were failing,” founder Mana Kimura-Anderson explains. “I like to think they were known as the ones to get the job done.” In her hands, the samurai myth is rebooted for the digital age—where the battle is not about safeguarding peace in Japan, but surviving an apocalypse brought about by the modern world’s dystopian and globalised unravelling.

Imagine Princess Mononoke wearing Hyein Seo, and you’d have a pretty solid blueprint for Kimura-Anderson’s alter ego. Creative by day, so-called “vigilante” by night, the UK-born Japanese-Ashkenazi art director is known online as “The Nunchuck Princess,” wielding her weapons in razor-sharp choreographies set to the experimental sounds of Akiko Haruna. “The look is definitely practical,” she says, describing her world-ending style of understated, oversized streetwear pieces, combined with utilitarian gear and high fashion. Her ultimate battle outfit is designed down to the elements. “In my end of the world, it’s not cold or wet, so I wouldn’t have to worry about big jackets,” she explains. “It’s Johanna Parv layered with Kevlar, and some kind of cross-body bag or harness for my nunchucks.” She’s at home in adidas, teaming tight high-neck vests with baggy basketball shorts, as in the accompanying shoot, styled with streetwear available on Zalando.

Kimura-Anderson’s self-professed “obsession” with Asian women in action began not with the Onna-bugeisha, but with video game characters like Tekken’s tenacious Jun Kazama. For too long, however, the ass-kicking femme role models she found in the fantasy-lands of [iconic Japanese video game maker] Namco, were the exception, and not the norm. “I cried watching Michelle Yeoh’s first fight scene in Everything Everywhere All at Once,” she explains, “because it suddenly made me realise how much I felt that I had been starved of that kind of representation.” Thus, what was born as a childhood infatuation has since grown into the warrior-focussed worldbuilding of Bugeisha Club, a collective of “creative athletes”, built upon lifelong alliances of mixed-Asian women.

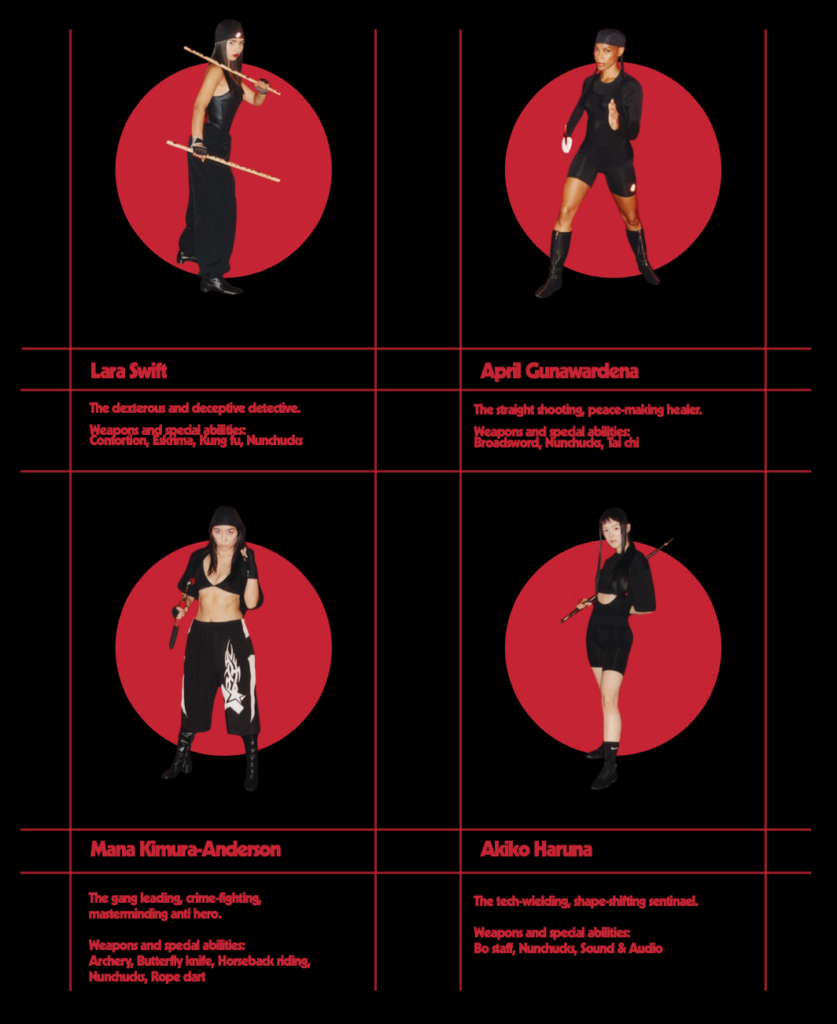

Beyond the Nunchuck Princess, Bugeisha Club is home to four further fast-acting agents: Akiko Haruna, the “tech-wielding, shape-shifting sentinel”; April Gunawardena, the “straight shooting, peace-making healer”; Tecky Becky, “the high-octane, high-kicking daredevil”; and Lara Swift, “the dexterous and deceptive detective.” Each character is a master of unique skills and set of special weapons, and brings their distinct cultural heritage to the collective to create a multi-faceted vision of modern femininity.

In many ways, Bugeisha Club’s aesthetic evokes the gritty, hyper-stylized worlds of anime like Psycho-Pass or Texhnolyze, in which urban decay and cybernetic enhancements mirror the internal struggles of their protagonists. For Gunawardena, a dancer and Pilates instructor, who has trained in Tai Chi for six years, the practice represents a meditative yet powerful form of resistance, combining grace with an underlying strength. “Although it looks soft and controlled it still feels very powerful, intentional and charged,” she explains. Bugeisha’s synchronised swordplay and co-ordinated crescent kicks establish a powerful prerogative that dispels the soft, submissive stereotypes often projected onto Asian women. Theirs is a rebellious realm where bodies merge combat and liberation.

Such is the power of representation. And the character-building that underpins Bugeisha is firmly rooted in the vivid depictions of women warriors that formed a fundamental basis for each member’s own sense of empowerment. Growing up in Thailand, Becky was captivated by the ceremonious intensity of Sumo wrestling and Muay Thai competitions on TV, but watching Mulan was a revelation. “I felt a deep connection to her character,” she remembers. “She was one of the few Disney princesses I could truly relate to.” Inspired by Mulan’s bravery and skill, Becky began training with a Bo staff, perfecting the fight choreography to ‘I’ll Make a Man Out of You.’ Lara was similarly emboldened by the daring depictions of Street Fighter’s Chun Li, and Lucy Liu in Charlie’s Angels, but only began exploring martial arts later on, practising Wushu and Shaolin Kung Fu before discovering Eskrima, the national martial art of her Filipino heritage.

While Western media may admire the elegance and lethality of characters like Yu Shu Lien (Michelle Yeoh) in Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, it frequently neglects the internal motivations and multi-dimensionality behind that facade—or uses silent, stoic killers as vessels for fetishisation. Hollywood has popularised a reductive trope of women warriors in bleak, dystopian futures, but Bugeisha Club’s interpretation of these scenarios carries a distinctly feminist and anti-colonial edge. “We take these ‘characters’ as extensions of ourselves,” Kimura-Anderson explains. “They are at once wholly independent—intrinsically linked to who we are—but come together to form a greater shared vision of community and of a team.”

The tight-knit nature of the group, composed of friends and collaborators, echoes the camaraderie found in battle-tested squads like Ghost in the Shell’s Section 9, or the ragtag crew in Cowboy Bebop. While pop culture often paints post-apocalyptic worlds as arenas for brute survival, Bugeisha Club imagines an apocalypse in which solidarity and protection take centre stage. “We’re not just fighting for the sake of fighting,” Kimura-Anderson has said previously. “There’s a deeper purpose of connection, of creating a world where we can exist on our terms.”

For these women, martial arts are an act of creative expression, a way to reclaim narratives that have historically erased or flattened Asian female experiences. And as a diasporic collective, holding space for the complex negotiations of heritage, homeland, and cultural belonging, Bugeisha’s characters don’t just fight external battles. They balance intricate tensions between tradition and modernity, bridging a personal connection to ancestral histories with the realities of living in diverse, globalised contexts. They become idealised or aspirational versions of themselves, providing orientation, grounding and direction. “We pour a lot of our soul into them. They have become a part of who we are, how we see ourselves, and who we want to be.”

Through their visceral, visually-striking universe of fashion-forward martial arts, Bugeisha Club is carving out opportunities beyond mere aesthetics. Their compelling world-building opens doors to martial arts classes, merchandise, film screenings, creative consultancy, and collaborations—already boasting partnerships with adidas Y-3, and features in Nowness and Vogue Italia. By crafting powerful, resonant characters, Bugeisha Club has already packaged itself into a dynamic product, ready for further creative expansion.

And despite their characters’ outward intensity, their approach is far from rigid or self-serious. It’s not about professing to be, or even becoming a master of martial arts, but using movement as a way to connect with cultural heritage, creativity, and each other. “I haven’t committed to the formalities of martial arts yet,” Kimura-Anderson admits. “My habit of picking up and dropping hobbies started young.” And the collective values experimentation and play more than precision. “Using nunchucks and eskrima sticks serves as a reminder that things aren’t always meant to come easily,” Lara affirms. “It’s been incredibly fun and fulfilling to be creative with people I love. We celebrate each other’s wins when they come, and keep each other encouraged when it seems something isn’t working out.”

Bugeisha’s world is one where perseverance and pleasure thrive just as much as combat readiness—and what it offers is more than just a martial arts performance troupe or a vigilante fantasy. It’s a reimagining of survival—not as an individualistic, isolationist act, but as a process of solidarity. Its agents are both defenders and architects of a world where triumph is defined not by brute strength, but by creativity, collaboration, and a defiant sense of identity.

Paid partnership with Zalando.