Cruising through romance, infatuation and co-dependency, Amelia Abraham unpacks the fact and fiction behind the U-Haul lesbian trope, and asks: What is love addiction?

How many girlfriends is too many girlfriends? How many times can saying “I love you” dissipate the weight of those words? Such are the questions I ask myself as another relationship severs serenely, implodes suddenly, or careens into a ditch. I do the maths: my age divided by “life partners” and I compare myself to people in long-term steady relationships. I consider that something hits harder about a gay breakup. It is just another reminder that I have once again failed at heteronormativity—evading the dating-marriage-baby pipeline. I compare myself to the messy, uncoupled queers in my life to make myself feel better. I wonder if “the one” is out there, and whether I want one, or many, or no one at all. I ask myself whether I am addicted to falling in love, because I have done it so many times and will surely do it again.

“Is it better to have loved and lost?” I ask Google. “Is it better to have loved and lost than lived with a psycho?” someone else has apparently asked the internet before me.

Love addiction, by its general definition, is a proposed model of pathological behaviour involving the feeling of falling and being in love. Love addicts tend to love “excessively” and “unhealthily,” although what constitutes those behaviours is up for debate. Historically, love addiction has been posited as a distinctly female affliction, coded as such by self-help books, romcoms about pining, distressed heterosexual women, and the regressive problem pages of women’s magazines, featuring dilemmas that verge on obsessive.

Perhaps the female coding of love addiction is also the reason it is so closely associated with lesbian relationships. It’s just one of the many well-established stereotypes about our romantic behaviour. We “U-Haul”—a reference to the US removal company—and move in with each other after the first date. There’s the “urge to merge,” the cliché that lesbians start to present alike after dating for a few months, sharing wardrobes, speaking the same, and becoming a hybrid. There’s the trope of the cat-loving lesbians—the notion that the moment we couple up, we abandon the gay bar, adopt a kitten, and never leave the house again. Instagram accounts meme-ify our sapphic and psychotic inclination to try to wed every person we meet, or to move countries for girls we barely know—guilty. A friend once told me that long-distance lesbian relationships must be causing climate change. “If you can survive a lesbian relationship, you can emotionally survive anything,” or so Twitter professes.

We love hard, yet not always enduringly. On TikTok, young heartbroken lesbians cry to the camera, and counsel each other in the comment section. On Tumblr, Blue is the Warmest Colour stills have become totemic for the pain of lesbian loss and longing, precluding the devastation of a relationship doomed to failure. With the lesbian divorce rate twice that of gay men, we seem destined for a “lesbian deathbed”—a term coined in 1983 by Philip Blumstein and Pepper Schwartz to describe the phenomenon of lesbians rapidly losing sexual chemistry after settling down.

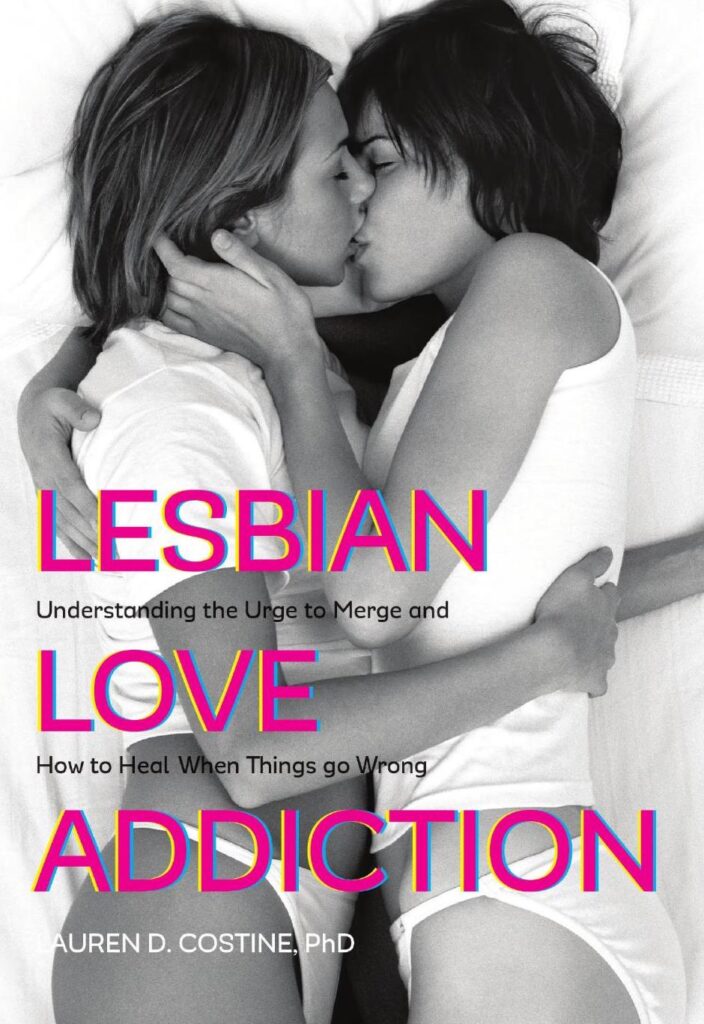

It feels ironic—or inevitable—that I am in the depths of post-breakup despair when I meet with Dr Lauren Costine, author of the self-help book, Lesbian Love Addiction: Understanding the Urge to Merge. It is the perfect time to be speaking, she reassured me over the phone from California. “How does one know if they’re a love addict?” I ask tentatively. Dr Costine’s book lists criteria ranging from falling in love quickly without really knowing the other person, to feeling addicted to the way love makes you feel, to having trouble setting boundaries. Zooming out, “you might realise inside there’s a voice telling you that something is wrong or off in the way you form relationships,” she says. It might be displaying a pattern, like repeatedly picking women who seem highly available but become instantly aloof once you’re together, or finding yourself infatuated with someone, but losing interest as soon as it becomes a relationship. “These are things to start looking at,” she summarises. “Especially if the pattern is impeding your ability to do other things well.”

“But are the clichés true for a reason, or do we end up fulfilling them because they are there,” I wonder aloud, “like prewritten scripts for what it even means to be in a lesbian relationship to begin with?” Dr Costine believes there are “very real reasons” for lesbian love addiction: female brains, female hormones, attachment issues, and societal lesbian-phobia. Dr Costine explains that this became clear to her when she began researching the controversial work of psychologist Louann Brizendine, whose book, The Female Brain, posits that cisgender female brains are less compartmentalised than cis male brains, and that in certain areas of the brain, we have more connective tissues around being relational—meaning we form stronger bonds than cis men. Cis women also emit more of the “bonding” hormone oxytocin in two very distinct situations, she says, when we are falling in love and nursing a baby. “Oxytocin makes you feel madly in love and can make you feel really high,” she explains, “so when you get two women together, emitting oxytocin at the same time, the high we can get with one another is more intoxicating.”

We queer women grow up in a heterosexist, homophobic, misogynistic world, Dr Costine points out. When we’re young, we internalise and activate feelings of not being good or loveable enough. When we jump into relationships and look for validation within them, we can lose our sense of self, especially if the other person begins to pull away. “That can be what happens when the honeymoon period is wearing off,” she explains. “Your partner grows more distant, and you haven’t really accounted for your own needs or been self-soothing while in the relationship.”

Dr Costine’s book has been met with criticism, both for its lack of nuance, and its focus on biology over a more societal or learned configuration of what equates to a same-sex relationship. One critic notes that love addiction is not included in the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders and therefore does not formally exist. The same reviewer argues that the book reinforces stereotypes about lesbians, and women more broadly. Not all lesbians are the same, they argue, although Dr Costine claims that was never her assertion. Rather, she aimed to provide a set of criteria of what some people might be experiencing romantically—to offer what she calls “that lightbulb moment”—as well as a blueprint for how to begin to break the pattern. “It doesn’t mean you have to walk around for the rest of your life saying, ‘I’m a love addict.’”

Whether or not women are more likely to be love addicts, or whether lesbians are more predisposed to the affliction because they are not-so-scientifically woman, Dr Costine is not the only one to assert the idea. Robin Norwood’s bestseller, Women Who Love Too Much—first published in 1986 and since translated into 25 languages—is a self-help tome packed full of Men Are from Mars, Women Are from Venus-style gender essentialism, as well as Sex and The City-esque sweeping statements about male and female tendencies, all packaged up as sage pearls of wisdom. The book offers case studies like that of Jill, the “slightly plump” blonde woman who can’t stop calling her disinterested boyfriend. It characterises love addiction as obsession, being unable to let go, or “measuring the degree of your love by the depths of your torment,” and firmly as a female proclivity.

While there are no formal statistics on the gender or orientation of people who attend Sex and Love Addicts Anonymous meetings, Dr Costine explains it is not an affliction reserved for lesbians alone. “There’s love addiction everywhere,” she affirms. The Love Addicts Anonymous web page may include a separate section for “male co-dependents and love addicts,” but Dr Costine believes we are moving towards a less gendered approach. Love-addicted tendencies are now more commonly characterised as “toxic behaviours” or “red flags.’’ We use this kind of language because we live in a more psychologised society, says Dr Costine, who believes that the erosion of mental health stigma, the proliferation of “therapy speak” and the more widespread inclination to “seek help” in its various forms were accelerated by the pandemic. TV shows like Couples Therapy—where lost and confused couples hash out their troubles with the help of their $700-an-hour uber-therapist Orna Guralnik—might prompt us to prod further at the parameters of what constitutes a “healthy” relationship. This may also explain a rise in conversations around attachment theory—or the four key behaviour types we develop in childhood and carry through to adult relationships: anxious, avoidant, disorganised, and secure. Dr Costine explains that attachment theory is helpful because its behaviour styles are not gendered, and can relate to specific attachments with specific individuals in life.

Dr Costine often returns to attachment theory when treating her patients—both discussing family dynamics and attempting to strengthen their bonds with themselves. While I don’t agree with all she puts forward, these methods seem fairly conventional and useful to me. Especially so when considering my own experience of feeling shamed by certain family members for not being able to “settle down,” but also feeling shamed when I do settle down, as though I’ll be judged as too conventional by my queer friends.

“When you work on yourself, what other people say or think or put on you will become less consequential,” Dr Costine says effusively, when I voice this experience. “We cannot control how other people think and act, but we can control how we think and act. I work with all my clients to keep looking at doing your inner work.”

Doing the “inner work” may be helpful. It has buoyed me through numerous breakups. But so too has doing the “outer work” of questioning and recalibrating our foundational notions of what constitutes love in the first place. That means overturning the idea that “real love” is love with a romantic partner, that it is spoken aloud and reciprocal, that it is enduring. Through necessity, queer people have disrupted convention, and lived life in non-linear ways. They have envisaged multiple or alternative means of existing, rejected by institutions like marriage and baby making. If, as bell hooks writes, the grief of heartbreak is in part a fear that love does not exist, then giving up hope in finding it is not the antidote. Lesbian love addiction will never be cured by eroding the belief that we are worthy of love, or losing the will to take risks because we anticipate pain. Instead, we might benefit from widening our conception of love, and finding it in more unexpected places.