On the last day before schools closed in the UK, students at one school in Camden, North London, sat down to an assembly in which their headmaster compared the coronavirus to several era-defining moments in history; The Spanish Influenza of 1918, 9/11, the 7/7 bombings in London. Coronavirus, he said, would be worse than any of these events.

“By the end of the assembly, my anxiety was through the roof,” says Sara, a teacher at the school. “I was worried the kids could see it on my face. I was trying to look strong and secure, but I could have burst into tears. They don’t really know about all the things he was talking about, but we do.”

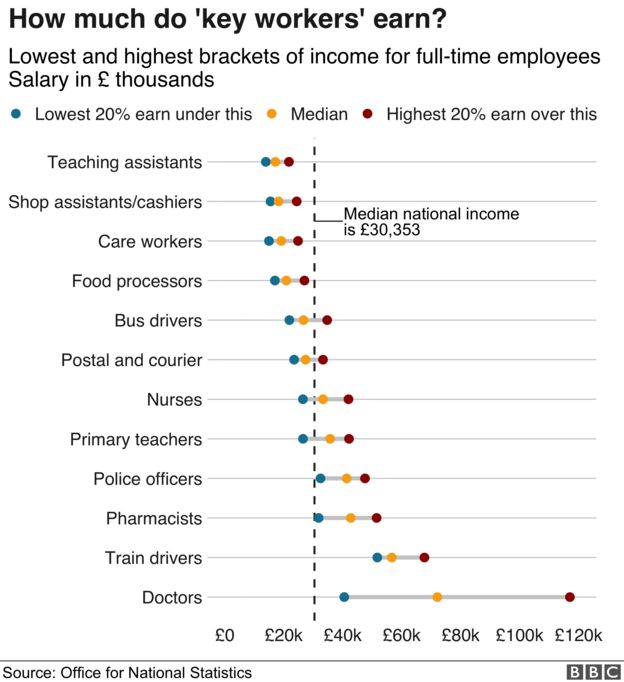

Schools in the UK closed their doors on Friday 20th March—to all except vulnerable children and children of critical workers—following the announcement of more stringent regulations on businesses, institutions and daily life nationwide. Prime minister Boris Johnson had outlined two days earlier that only “key workers”—including healthcare providers, postal workers, teachers and supermarket employees—would be ‘permitted’ to go to work, while the rest of society would be expected to quarantine, confined to their houses. But what has life been like for the other half of British society, the “key workers”, from frontline NHS staff to teachers to shopkeepers, who are some of the most essential, yet underpaid workers in the UK—for whom Boris Johnson took to the pavement outside No 10 to applaud and “support”, but who are among those worse affected by the Conservatives austerity measures?

“My personal life has changed massively,” explains East Anglia paramedic, Michael, who has been self-isolating since before the official lockdown, due to health and safety regulations outlined by the NHS. “We are expected to suppress our worries and fears about the coronavirus and get on with the job, but it has already caused such a large psychological impact on our lives. We go to work, then we self isolate, whilst worrying whether we may have infected those we have come into contact with. We are unable to get groceries, toiletries, see loved ones and not knowing how long we will work like this—and that’s hard.”

Michael’s team is understaffed, undersupplied and underprepared—at the time I speak to him, he and his coworkers have still not received any formal training on how to properly apply protective PPE-wear, and have run out of hand gel and masks on multiple occasions. And when news comes that the UK government has failed to secure at least 16 million face masks for frontline staff, hearing Boris Johnson uttering the phrase “our NHS” is enough to make any Labour-voter wince.

Michael wears basic PPE (which includes a surgical mask, apron and gloves) for any suspected coronavirus cases, and only wears full PPE (FFP3 mask, bodysuit, visor etc.) for confirmed cases. Naturally, for ambulance call-outs, most of the cases are only suspected. “We are not adequately protected if we do come into contact with a corona case, and we are advised to leave those with non life-threatening symptoms at home and tell them to self isolate, so will never know if they tested positive or not.”

Trainee GP Fiona, who works in North East Scotland says the NHS protocol is constantly changing. “It feels like the advice we get can change hourly. We get so many emails every day about how we should go about treating high risk patients.” Up until a couple of weeks ago, Fiona had been stationed in Obstetrics and Gynaecology, but was quickly relocated. “I got an email from the consultants one day to say thank you for my time in the department and good luck going forward. That’s how I was told I was being reallocated.”

She is now working in Combined Isolation Assessment, or CIA, where patients with COVID19 symptoms are triaged and taken to the correct place for further treatment. But the main criteria—exhibiting a temperature and a dry cough—is very common, and Fiona says the area will likely soon be overwhelmed. Luckily, she has experience working in A&E, and is used to the fast paced, high stress, high pressure atmosphere it entails, but some of her colleagues are not so fortunate, and are being thrust in at the deep end.

Thankfully, staff are now finally being tested for the virus, and though news broke today of thousands of NHS workers having to be re-tested due to flawed checks, when Fiona had a fever before a night shift, she was quickly screened and given the all clear. Previously, she would have had to take at least seven days off work. “The NHS cannot afford to have so much of its workforce off sick, and so testing has become a priority,” she explains. Staff now also have access to an on-site psychologist to help them deal with the emotional effects of the crisis. “But like so many of these initiatives,” she stresses, “it’s the people who need it most who are too busy to access it.” Instead, Fiona and her colleagues are doing their best to lift each other’s spirits. “The work WhatsApp group is a refreshing relief from the intense emails—there’s lots of memes involved.”

The crisis is also affecting all manner of NHS staff, including those who are not facing the virus head-on. Annabel works in a residential rehabilitation centre for patients with acute mental health difficulties. It’s a 10-bed house, staffed 24/7. “It’s been feeling pretty frantic,” she admits. “For the people who use our service, there’s been a lot of uncertainty. The rapidly changing advice has meant that we’ve been unable to answer a lot of their questions, or provide concrete advice on what the virus means for them.” Residents are also not permitted to visit their friends and family—a difficult rule to explain and enforce. For the staff, priorities have also shifted, from a 100% focus on supporting service users, to simply ensuring the service is able to run at all—ensuring shifts are covered when staff become ill, and implementing new hygiene and social distancing measures. “Our work now is more about putting out fires. It feels as though everything’s been put on pause while we get through this.”

The same goes for teachers, says Sara, who has found it difficult to know how to handle the student’s uncertainty. In the last weeks of school, many of the teachers were becoming unsettled too. “We were getting really agitated,” Sara admits. “Everyone around us seemed to be staying at home and social distancing, and we were literally gathering in hundreds every day in a building that’s not hugely hygienic with lots of kids who are carriers. We integrated the virus into lessons, but it felt weird to educate them about social distancing when we were practicing the opposite. They were told in that assembly to avoid their grandparents, but lots of them live with their grandparents.”

Sara says attendance in the last couple of weeks dropped dramatically, and many GCSE students, whose exams were cancelled, felt that their revision and hard work had become essentially obsolete. “I hope this situation changes the way we view learning,” Sara says. “They’ve been taught that exams are everything, that their entire education builds up to one moment—and it shouldn’t be like that. We need to teach them that there’s value in every part of the process.” In this sense, the pandemic underpins the agenda the Labour party have been pushing for since and before Michael Gove’s drastic school reform and cuts to children’s welfare under the Conservative government. Although the scheme has come under fire in recent days for its difficulty to access, by recognising the need to continue free school meals—which for almost a third of children constitutes their main meal in the day—the government is forced to recognise that school is about so much more than academia.

Aside from uploading worksheets and assignments to the school’s virtual learning environment—a much more hands-off teaching approach—Sara is also now assisting in the supervised learning programme outlined by the government. “There’s a list of kids who are allowed to come into school,” she explains, “the children of key workers, kids with EHCP, kids in care or anyone on the child protection register. We’re there for them.” Sara estimates that there are around 60-70 pupils at her school who are eligible, however normally there are only a handful who come in. “There’s no one forcing them, or checking up on them if they don’t,” she says. “But for the ones who do come in, it’s been really nice. It must be so strange for them being in this huge empty building—going from 1500 people to just 15—but they’ve been really good about it. I just worry about the kids, not just in my school but worldwide, who need school as a refuge. School is a safe space for so many kids and there can be things going on that we don’t know about.”

Among those still working are also delivery and postal employees, emergency services, police officers, journalists, broadcasting houses, construction workers (who can continue to operate so long as they adhere to the six foot rule) some hotel staff, and retail staff selling “essential” supplies or services. But it is the responsibility of each employer—be it the Royal Mail or Tesco—to protect its staff and customers. In the US, there have already been reports of “terrified” UPS employees in going to work while sick, for fear of losing their jobs, and under strain at the moment, it’s difficult to know how seriously safety measures are truly being treated and implemented in the UK.

For Aadi, who runs an off-license in London’s Sussex Street, things are somewhat easier (as there’s no bigger corporation in control) but things are still difficult. The cash desk has been blockaded with plastic crates in an effort to keep a safe distance between staff and customers, and employees are wearing protective gloves and using disinfectant. “We are worried about getting the infection,” he admits. “There is lots of information about young people not having symptoms and spreading the virus which is scary, but we see our work as essential—and especially with big grocery stores being so busy, it is important for people to feel like they can come to our store even if it is just to buy something small.”

If this crisis has taught society anything, it’s just how essential the UK’s essential services truly are. They’re among the industries that have faced the most severe cuts over the last decade, and yet, they’re those on which we most rely to function. Despite being overstretched and underprepared, British key workers are adapting day by day, but the infamous British mantra “Keep Calm and Carry On” from 1939, will not suffice now. “Times like these teach us we have to adapt,” says Sara. “Things need to change, both in the short-term and in the long-run, and all we can hope is that it finally happens.”