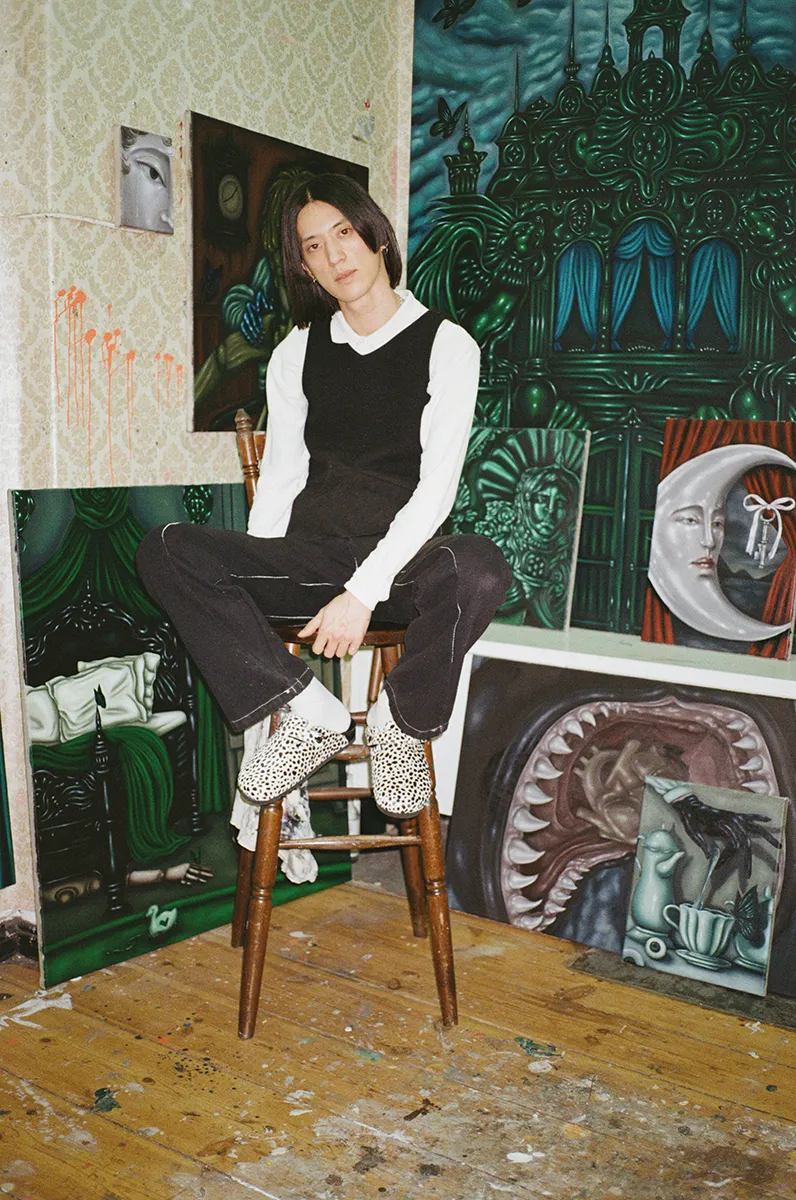

Self-taught Japanese painter Ryo Koike navigates worlds of paints and pigment. Grounded by the aesthetic comfort of Scholl shoes, his hands are guided by instinct, precision, and the quiet ritual of craft

For years, Ryo Koike avoided painting eyes. Doll-like bodies, winged angels, and slender devilish beings appeared in dreamlike scenes—with only dark cavities above the nose. Each creature occupied a fantastical world, surrounded by tentacular plants, fragile butterflies, and sombre mythical beings, unseeing. “When I started painting, I didn’t feel confident enough in my technique, so I purposely left the eyes blank until I felt ready,” the Japan-born, Berlin-based artist recalls in a gentle, spirited voice. “Eyes felt so important, they reveal everything.”

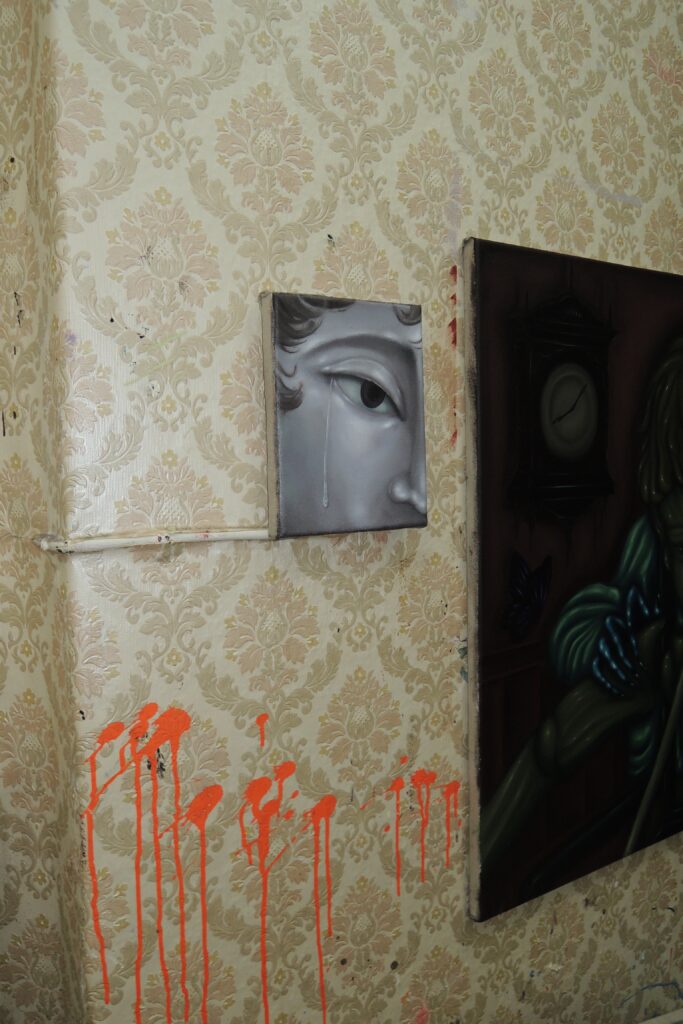

Stepping into Koike’s groundfloor studio in Berlin’s Neukölln neighbourhood, however, I see eyes everywhere. In one painting, a lone eye cropped from a silvery, steely face looks past me absently, a long, suspended teardrop leaking from the outer corner. In another, a putrid-green boy with a nose extending beyond the canvas wears a melancholic gaze that jars against its glossy reptilian facade. In Eye Contact (2025), a painting smaller than a sheet of A4 paper, a third eye is seen above thin brows, framing the two distraught orbs below. “It comes from a nightmare,” explains Koike, “I was walking through a restaurant when, suddenly, I felt an eye coming out of my forehead. I went to the bathroom quickly and [saw it] in the mirror. It was painful, and I felt so embarrassed.”

Koike had finally started painting eyes two years prior, after a pivotal encounter at the Surrealism and Magic: Enchanted Modernity show at Museum Barberini, in Potsdam. The exhibition revealed a profound Surrealist engagement with magic and the occult, featuring artists like Salvador Dalí, Max Ernst, Leonora Carrington, and Remedios Varo. “I left so inspired I ran back to the studio and made this painting,” he says, gesturing toward I sink into a dream before I sleep, in which an elfish figure with vacant blue eyes in billowing clothes !oats in saturated teal currents, arms outstretched, while a midnight-blue claw anchors his left shoulder to darkness. “In my paintings, the eyes are always avoiding direct contact,” Koike reveals. “Personally, I also try not to make eye contact.”

Koike grew up in Nagoya, Japan in the ‘90s, before leaving for Tokyo after high school. “My hometown was a mess,” he remembers, laughing timorously, with a sudden reticence. “A lot of traumatic memories.” In Tokyo, he wasn’t sure what he was searching for, but he found his first love—and first heartbreak. In 2016, he relocated to Berlin to get a break from Japan, where conservative values and the ceaseless pace of life had him feeling lost, overwhelmed, and out of place. Surrounded by motivated art students, he was inspired by their passion and began drawing and painting in earnest.

Though still unsure of himself, he applied to the Berlin University of the Arts in 2018 and 2019 —and was rejected both times. Undeterred, he kept painting. “I realised making something gave me something in return. It reflected my emotions, like looking in a mirror,” says Koike, who didn’t intend on becoming a painter at the time. “Painting was a kind of meditation. Other people go to the gym, do yoga, meet friends, or go to parties. I need to paint—it guides me and makes me feel stable, mentally and physically.” His early works, mostly acrylic on paper, leaned towards abstraction, though he admits the details are hazy now, blurred by the difficult period he was navigating. Gradually, his paintings grew more figurative, drawing inspiration from Grimm’s Fairy Tales, and he experimented with oil painting techniques.

Clothing RYO’S OWN Shoes SCHOLL

Learning alone was slow and often frustrating. “When I began painting, I didn’t know how much oil to use, how to layer, or how to change brushes,” admits Koike, who approached painting like he learned English and German—by mastering the basics. “I looked techniques up online, but it was more about trying things out. I struggled a lot, but over time, I developed a sense for it, like muscle memory. Some days I couldn’t paint at all. I felt useless. But other artists told me, ‘That’s part of the process. Some days you’ll do nothing, and other days you’ll work 14 hours.’ So I kept going to the studio, even if only to touch the canvas for a moment.” He remains persistent about prioritizing painting in daily life, determined not to lose his hard-won techniques. Though he’s now confident painting faces, he admits bodies still elude him. “Learning to paint feels endless. There are so many things to learn.”

Against the paint-splattered white walls and faded tan wallpaper of his studio, Koike’s palette of deep greens, chrome greys, and piercing reds glows with its own, otherworldly aura. Paintings are everywhere—leaning against each other on shelves, hung on walls, standing on the floor. Found objects cluster on wooden shelves like offerings: a marbled, claw-like sculpture, a marionette, dried flowers, doll parts, a baroque-style mirror, a framed butterfly. That day, the sun was out, but the curtains were drawn.

Clothing RYO’S OWN Shoes SCHOLL

Since 2023, his canvases have embraced a darker chromatic vocabulary, though always punctuated with lighter elements, like the butterfly, which for him symbolise love, hope, and peace. His recurring motifs are now rendered with more depth, detail, and luminosity: mournful eyes, anatomical hearts, baroque-style pendants, and faces sheathed in chrome-like armour. The latter he traces to his childhood fascination with Pinocchio—the wooden-carved puppet who longs to be a real boy. What captivated him most was the way Pinocchio’s nose grew with each lie, caught between artifice and authenticity. For Koike, politeness often demanded small acts of dishonesty, a kind of armour, and the puppet became a symbol of his own youth in Japan. “Nobody knew how I truly felt. I couldn’t be honest there. I was, like, literally, a puppet,” says Koike, who now balances painting with working at a cafe part-time.

Painting has become a method to tune into his own emotional terrain and to those around him. It has also opened him up socially, especially in the queer nightlife circles he moves in. He’s collaborated with The Evil B-Side Twins for an album cover, seen his work appear on club night posters, and on Berghain’s May 2023 programme. His paintings have also been exhibited at ACUD Galerie in Berlin, Galerie Holešovická Šachta in Prague, and Cazul101 in Bucharest, among others. For Koike, painting is a portal into the unutterable—those inner worlds that evade language. “Sometimes when I want to explain a feeling, memory, or something inside my body, I can’t,” he says, “But with painting I can. It’s like a translator.”

Paid partnership with Scholl.

Photography IGA DROBISZ