INSIDE THE CHURCH-FUNDED FETISH ARCHIVE BOASTING BRITAIN’S BIGGEST GAY PORN COLLECTION.

For 37 years, a set of unassuming graffiti-scrawled doors just off Mile End Road in London’s East End opened to reveal a blacked-out pub brimming with whips and chains, oil drums lining the floor and rubber boots suspended from the ceiling. This space belonged to The Backstreet—the longest standing gay leather bar in the UK capital, catering to a devoted crowd of kinksters and notorious for one of the strictest rubber-loving dress-codes in the scene.

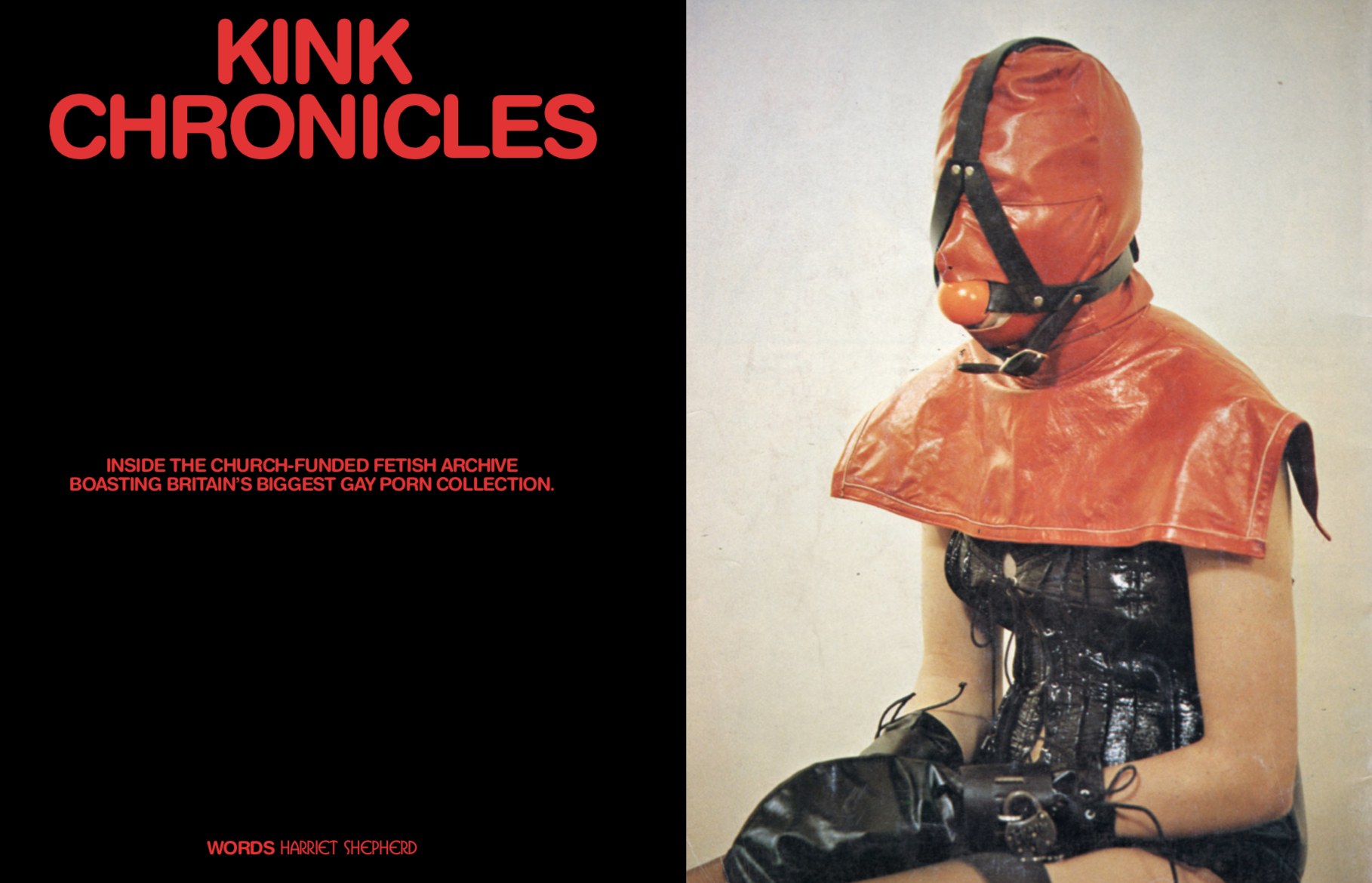

When The Backstreet closed its doors last summer, it joined The Black Cap in Camden and The Joiners Arms on Hackney Road in the growing graveyard of London’s lost LGBTQ+ venues. But its boots, beer taps, and legacy live on in an unlikely basement opposite Liverpool Street station. They’re stored in a set of large plastic boxes, beside trays of Motor Sports Club members’ badges, and beneath a pair of ballet pointe stiletto boots somewhere between the infamous Armadillos Alexander McQueen designed for his final collection and the Lynchian Louboutins of 2007. This pair pre-dates either. “That’s Jeri’s bondage gear,” explains Stef Dickers, head archivist at the Bishopsgate Institute, with characteristic nonchalance: it’s hard to faze a man who’s spent seven years unpacking boxes of fetish memorabilia.

In the 18 years he’s been at Bishopsgate, Dickers has helmed the institute’s transformation into the biggest LGBTQIA* archive in the UK. And since 2016, he’s spearheaded its collection—and celebration—of fetish culture and history. It’s a noble cause, especially as the city’s fetish spaces, like The Backstreet, become fewer and farther between. In Tower Hamlets, the borough which Bishopsgate calls home, 73% of queer venues had already closed by 2017, according to research by UCL. In 11 of London’s boroughs, none remained whatsoever.

In 2019, the district’s deputy mayor called The Backstreet “an important community asset”, claiming the council was “going the extra mile… to protect safe spaces for our diverse community” and ultimately blocking plans for a 12-storey flat proposal in its place. Three years later, authorities threatened the closure of two of the city’s burgeoning kink and fetish parties, Klub Verboten and Crossbreed, in an attempt to “prohibit nudity and semi-nudity” in venues across the borough.

Such stories make Bishopsgate’s existence, nestled unassumingly between a Pret A Manger and a Boots in the thick of the capital’s commuter foot traffic, all the more extraordinary. “We’re one of the very few places that not only accepts [fetish], but more importantly that celebrates it,” says Dickers. “It’s a history that matters, it’s a history that’s important.”

Even more extraordinary is the fact that this subterranean haven of fetish—a repository of rubber dildos, lesbian erotica, and a trove of pulp fiction that’d give Tarantino a run for his money—was established by an institution that once believed homosexuality was a dance with the devil, and tortured and executed practitioners of ‘sexual deviancy’. “We were established on money left to the Church between 1481 and the 1890s,” Dickers explains. In 1891, eyeing the mammoth income generated by churches across the UK capital, the Charity Commissioners introduced a scheme to encourage the philanthropic redistribution of Church assets. This means that, even 128 years after its establishment, the Bishopsgate Institute remains independent of government or Arts Council funding. “People would leave half an acre of swampland in Aldgate to the church in 1532, which by 1850 is half a square mile of real estate property. Lucky for us, [St Botolph-without-Bishopsgate] had quite a radical vicar.”

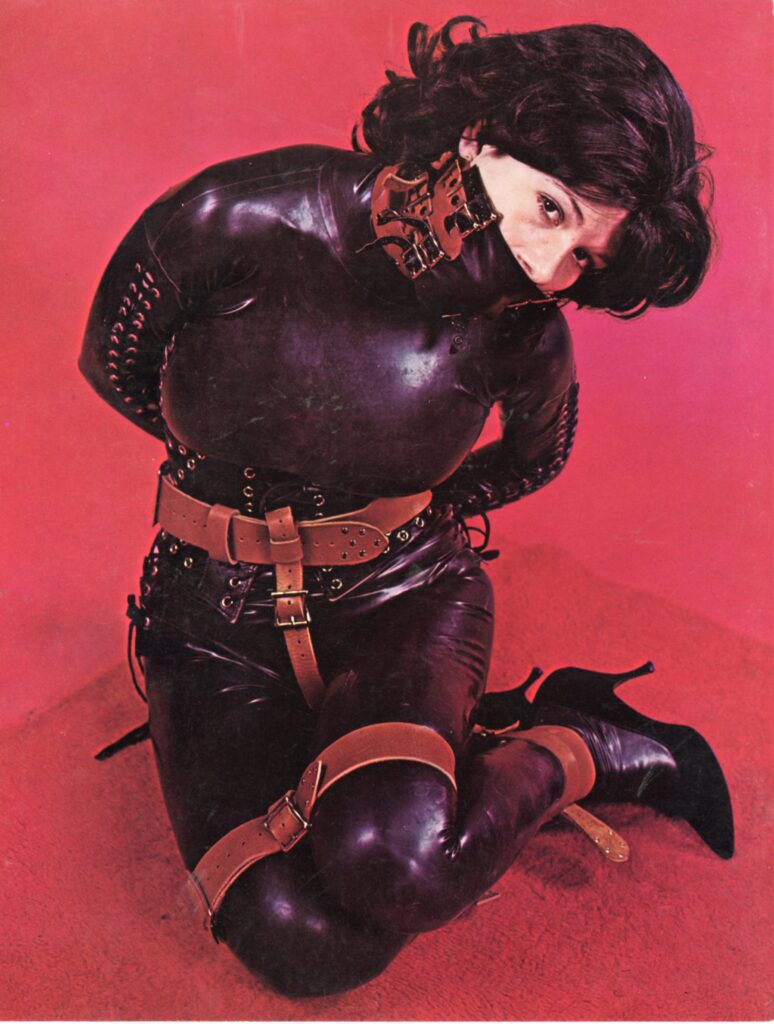

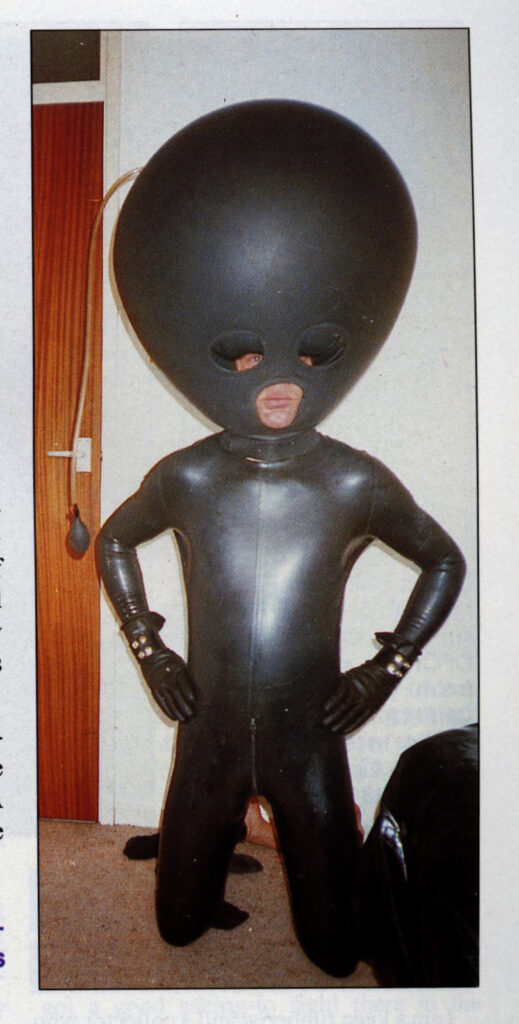

Radical as Reverend William Rogers may have been, Bishopsgate’s trajectory from a public library and cultural education centre to a trove of X-rated erotica is likely much more than he bargained for. Walking through rows of acid-free archive boxes, Dickers adds colourful quips about its contents. There are shelves upon shelves of literature (“on and on it goes”) including Flagellation & the Flagellants: A History of the Rod, from 1896, and the History of Whipping “which belonged wonderfully to Frank Cushing of Cobham in Surrey.” There’s masses of Macintosh content— “a bit of an older suburban outfit”—and just about every fetish magazine ever published: Janus for spanking, Splosh! if you prefer things wet and wild. “We got offered 28 scrapbooks of rubber fetishism from a leading member of the Conservative party,” Dickers explains. “We’ve never found out who it is, but from [the] ‘40s through to the ‘80s, every time he’d see a pair of boots, he’d cut ‘em out. In the ‘70s and 80’s he was literally cutting out pictures of Cilla Black.”

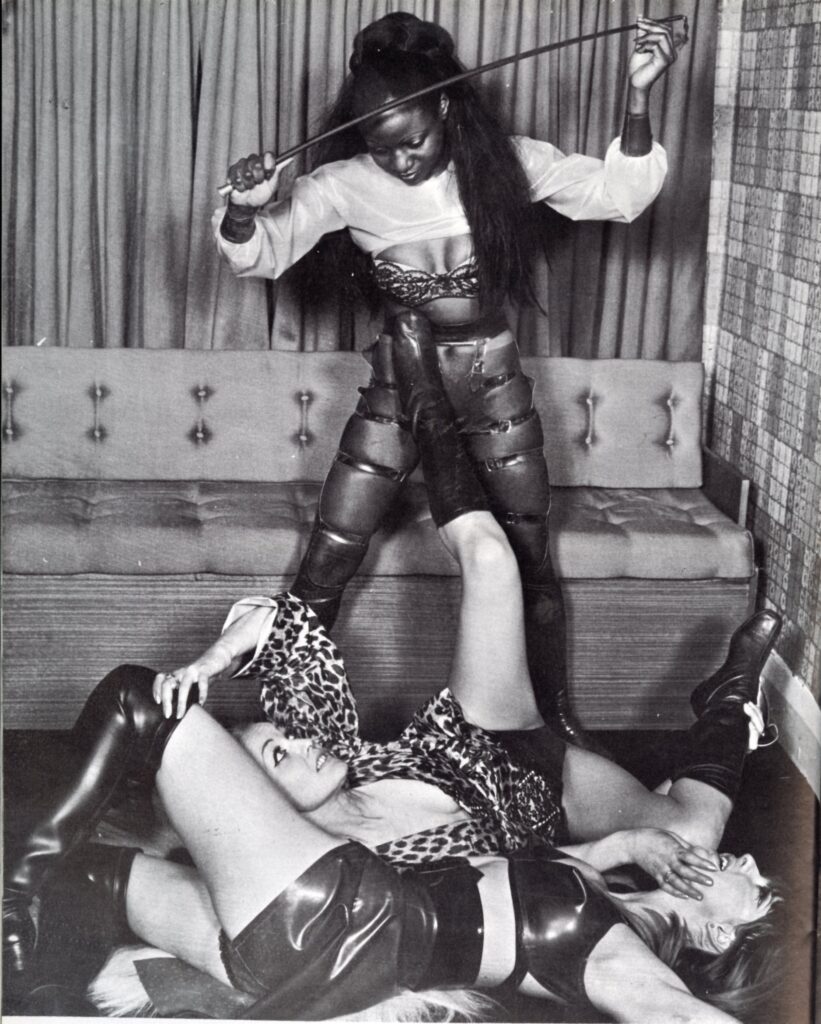

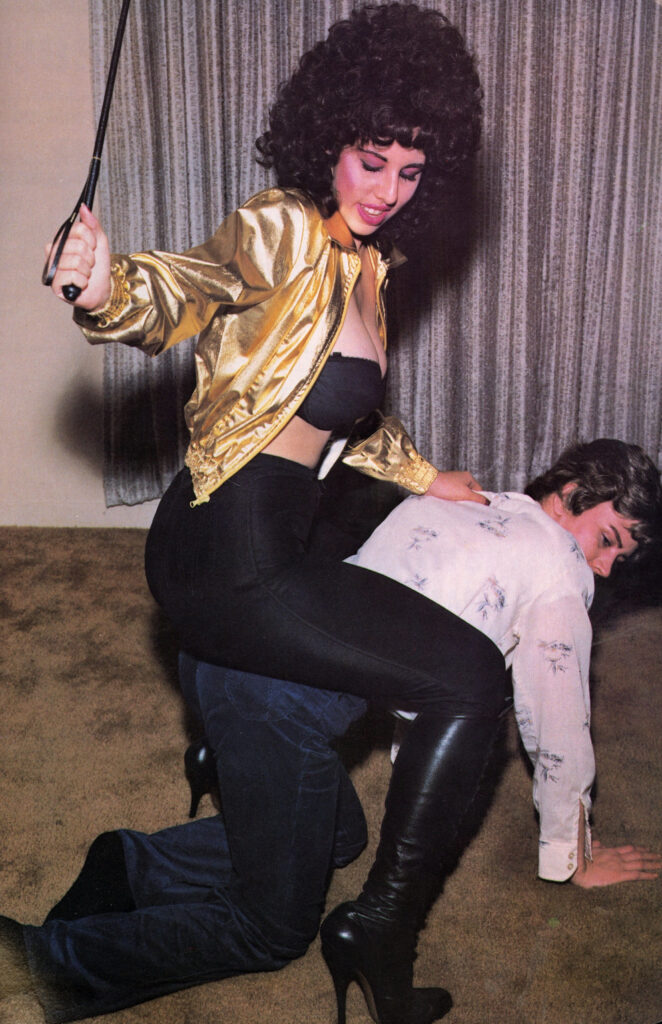

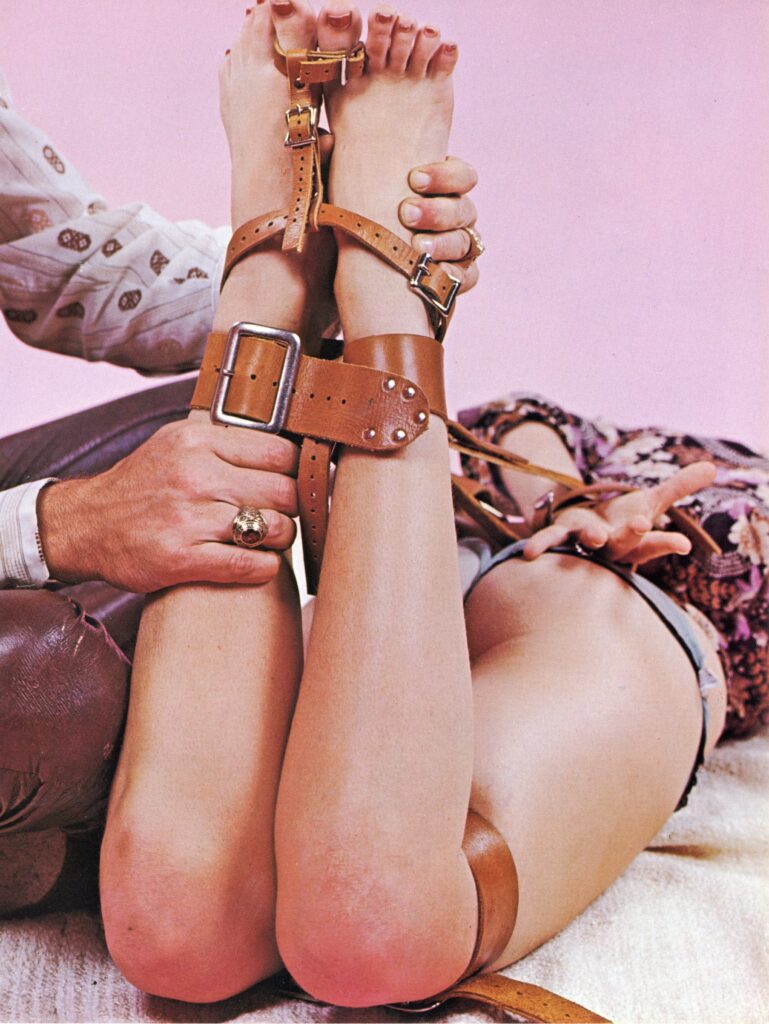

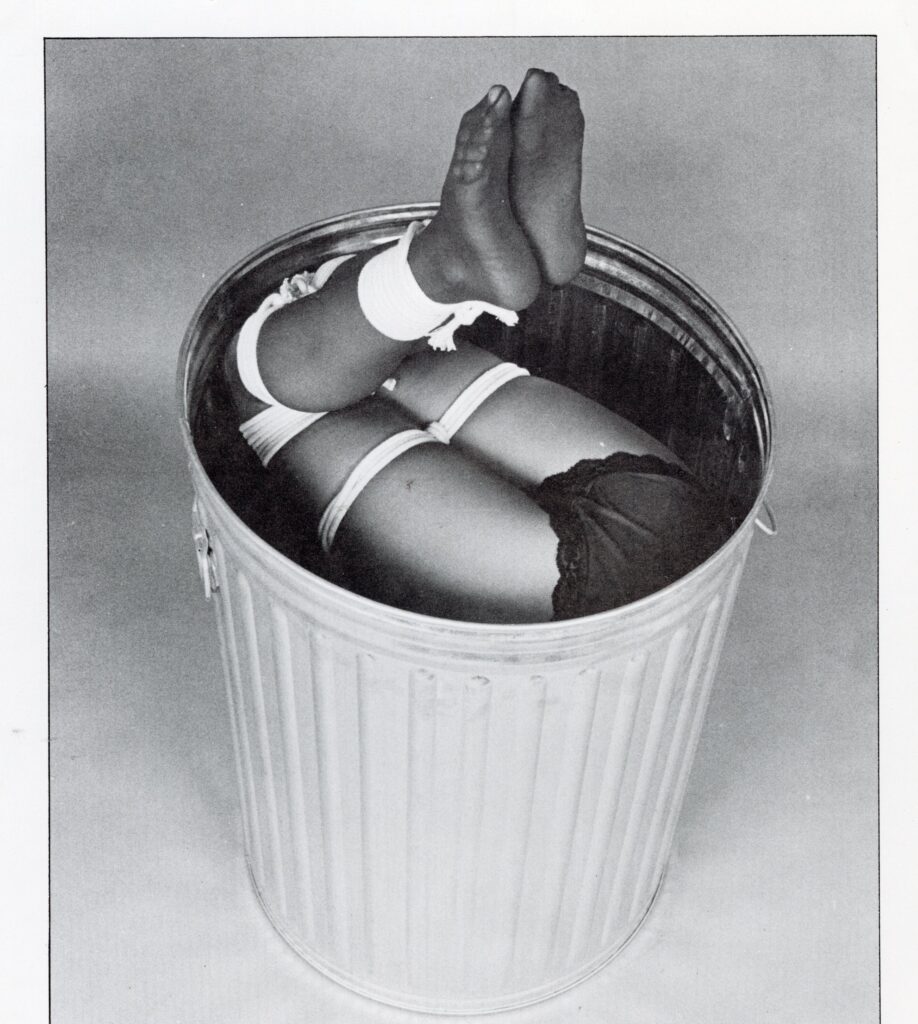

Much of what exists in the archive is male-authored and of heterosexual persuasion, and a significant portion of it not only lacks alignment with today’s standards of political correctness but also raises significant ethical concerns when examined from a contemporary standpoint. Misogyny runs rampant, and much of its material reinforces racial stereotypes, bolsters the fetishisation of Asian women, and endorses harmful transphobic narratives. But, as Dickers affirms, such artefacts serve as essential educational resources that vividly depict the evolving perspectives on LGBTQIA* and fetish culture, shedding light on the broader shifts in British social and cultural history. In curating workshops, lectures, and dialogues led by prominent professors, academics, and artists, Bishopsgate endeavours to foster a profound comprehension of the complexities encapsulated within these records and encourages a nuanced exploration of how these materials contribute to our understanding of societal progress and change.

The issue of diversity is one that Dickers is acutely attuned to, but the archive’s lack thereof can be traced in the shadows cast by the historical persecution of homosexuality in the UK, where it was only partially decriminalised in 1967, and was still considered a mental illness by the World Health Organisation as recently as 1992. “People will come in and ask, ‘what have you got of lesbians in the Second World War or gay men in the ‘20s?’ and it’s like, well, not a lot. You didn’t keep love letters and photos of you snogging your lover because you’d go to prison if they were found.”

Coincidentally, a few days prior, Dickers had received a phone call from someone who had discovered a series of fetish photograph negatives bricked into a wall while renovating their new house in Horwich, near Bolton. After some investigation, it turned out they belonged to a former ice cream man who had been convicted in Operation Spanner. In the late 1980s, the Spanner case saw 16 men put on trial for over 100 offences after authorities discovered a video of them engaging in consensual same-sex sadomasochistic activities, in a legal saga that has become historicised for its homophobic handling. Unfolding against the backdrop of the AIDS crisis, at a time where 75% of the UK population believed homosexuality was always or mostly wrong (according to the British Social Attitudes Survey of 1987), the investigation and court ruling were lambasted for their homophobic sentiment. Eight of the men were sentenced to prison for ‘occasioning actual bodily harm’ and ‘unlawful wounding’. “It was just absolute bollocks,” says Dickers. . “[The video] was all very innocent and consensual, but these men were sent to prisons that housed serious and dangerous criminals.”

These recovered fetish photographs will now join Bishopsgate’s continuously-expanding archive, which also houses the collection of Roland Jaggard, one of the most infamous convicts in the Spanner trial, and the Rebel Dykes, a group of radical post-punk London lesbians whose activism effected tangible societal transformation in the ‘80s. “It’s becoming more and more queer,” says Dickers, “and with the contemporary collections, we’re really focussing on being more representative.” Bishopsgate has also recently inherited the entire contents of Centurian, the US’ oldest fetish archive, founded by fetishist Jeri Lee (creator of the ballet boots) in Reno, Nevada.

And while Bishopsgate’s fetish account fights a near-constant battle against Instagram’s community guidelines, and its basement boasts graphic book-fulls of pierced penises, not all of the archive’s material is explicit or X-rated. “The first fetish collection we ever got [from a motor sports club in Birmingham] was like the most intricate minutes I’ve ever seen of any organisation ever,” says Dickers. “Vol au vent preparations for Ken’s birthday at the Green Man, newsletter notes, editorial committee meetings…” Somewhat ironically, it’s actually these kinds of unspectacular, unsexual, and everyday items that end up embodying the fetish archive’s greatest achievement: humanising those who have historically been dehumanised.

Images THE BLACK COLLECTION & UK FETISH ARCHIVE courtesy of BISHOPSGATE INSTITUTE