Billy Idol on the prophecies of his forgotten Cyberpunk album and staying true to his vision against all odds.

In a grainy YouTube video with scarcely 5,000 views, a 38-year-old Billy Idol—complete with sunglasses and signature bleach-blonde spikes—grins while late LSD advocate and cyberdelia spokesperson Timothy Leary mutters, “Turn on brain, turn on brain. Activate galaxy within.” Around them, a handful of people flail about— waving audio-emitting speakers and whispering to a microphone shaped like a human head. A lower-third graphic overlay describes the noisy ritual as “Feeding the Cyberhead 3D sound recorder.” If it wasn’t for the picture quality and the decidedly ‘90s lava lamp cameo, you might mistake it for some kind of pseudo-spiritual rehearsal for next year’s Burning Man.

This behind-the-scenes footage is only a small part of the expansive multimedia universe constructed around Idol’s Cyberpunk record, drawing on New Wave science fiction and released to critical failure in 1993. “I don’t think people really understood what I was talking about,” he explains via Zoom, thirty years after releasing the narrative concept album inspired by the speculative literature of the likes of William Gibson and Neal Stephenson, as well as the then-nascent cyberdelic counterculture of the early ‘90s. “There was only a small clique of people who were really into it, so we were seeing the future.”

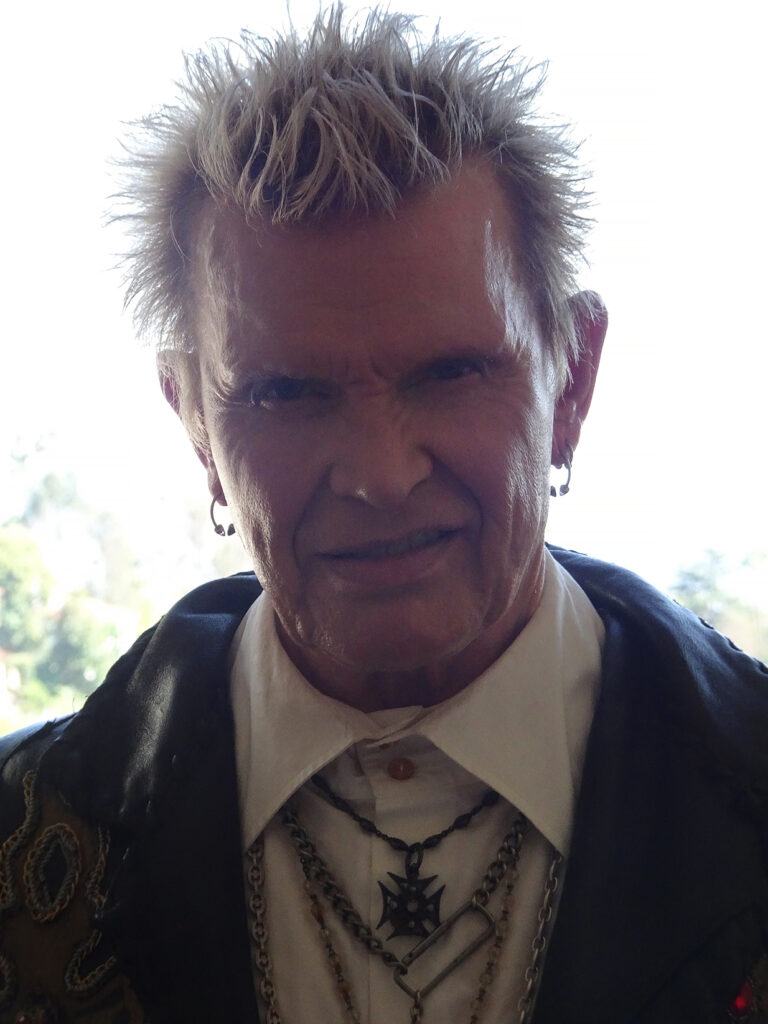

Better known for his beloved ‘80s glam-punk classics, like ‘Rebel Yell’ and ‘White Wedding,’ Idol had reached a career peak following the commercial success of 1990’s Charmed Life. But there was more going on in the background—beyond the fresh mullet and steampunk aesthetic of that album’s cover art—which ultimately led Idol toward the biggest gamble of his career. “I was also trying to get hold of my life, in a way, and get a hold of my drug addiction, things like that. So there’s a lot of things in the album. There’s stuff about the climate crisis. There’s stuff about what we’re doing to our bodies. There’s stuff about me even trying to use meditation and go to a higher self. And, I get it, people aren’t going to go from Charmed Life to that,” Idol adds with a chuckle, now in his late 60s, his still-textured hair poking out from the blurred background of a browser window. “I was trying to go from this kind of super rock ‘n’ roll life into, ‘Wait a minute, I’ve got children.’ I’m trying to take stock, in a way. I’m trying to develop, and this is how I was doing it.”

Coat BILLY’S ARCHIVE Shirt VINTAGE VIVIENNE WESTWOOD Necklaces LOREE RODKIN and BILLY’S ARCHIVE

Consisting of thirteen tracks, and a handful of audio interludes, Cyberpunk is what Idol calls a sample record, made up of dance and industrial influences and synthesised vocals, as seen in songs like ‘Power Junkie,’ ‘Tomorrow People,’ and the album’s second single, ‘Shock to the System.’ The chiptune-sounding motion of ‘Wasteland’ features an excerpt from Mad Max, courtesy of Warner Bros.; and Brett Leonard—who directed four of Cyberpunk’s five accompanying music videos (using a graphic technique called ‘Blendo’)—incorporated samples and snippets from his famous 1992 The Lawnmower Man horror-film adaptation of Stephen King’s CyberGod screenplay. A spoken-word intro to the album has Idol reciting the words to technology and cyberculture writer Gareth Branwyn’s 1992 manifesto, ‘Is There a Cyberpunk Movement?’ His voice is pitched, distorted, and submerged in heavy reverb, as he proclaims: “The computer is the new cool tool.”

“It really happened because of the recording machines they were starting to make, which were starting to be computer-driven,” Idol says about one of many factors that led him toward making one of the least understood but, arguably (or retrospectively), most interesting projects of his career. “A lot of things happened after the recording of Charmed Life, and that led to me doing something like this Cyberpunk album. I was saying, ‘How long can I live the way I’ve been living?’ It was fun, the way I’d been living, but also, it was weird. Through MTV, I’d become a television star,” he says about the newly established music video channel’s impact on his public profile. There was the stark close-up of Idol staring back through the camera lens at his viewer in eerie soft-rock ballad ‘Eyes Without A Face,’ or the swaggering hard rock of ‘Rebel Yell’—filmed on a stage in a cowboy shot frame. “It’s totally different from being a cool musician that people know. It’s like every asshole in the world knows what you look like because they’d all seen the video. They might not even hear the song.”

In losing touch with one reality, Idol saw a way to connect with another. Cyberspace offered him the possibility of anonymity and transcendence—an increasingly appealing prospect as the price of celebrity took hold. “You start to live in a little room,” he says, recalling how circumstances changed for him as part of the so-called ‘Second British Invasion’ of punk and new wave artists taking the US market by storm in the early ‘80s. “And that’s kind of why all the drugs. You think, ‘How can I travel when I live in a little room all the time?’ That was partly the appeal of the cyber thing. Going, ‘Ah, the way you could travel in a little room is through virtual reality and the internet,’” Idol adds, laughing. “It was all a bit of a revelation of what was possible in the future, or what was even possible at that time.”

Jacket BILLY’S ARCHIVE

Cyberpunk was well ahead of its time in terms of applying those possibilities to the promotional cycle, whether it was in plans for a supplementary CD-ROM (which never materialised due to poor sales following the original album drop), or a limited edition pack containing both a compact disc and a floppy disk artist bio. According to a print advertisement in a 1993 issue of Californian cyberculture magazine Mondo 2000, the storage format was compatible with the “Macintosh Color* with 3MB of RAM.” It also encouraged fans to “Contact Billy in CYBERSPACE” (at [email protected])—quite possibly the very first time a major artist had attempted to connect directly with their audience via email. “I even did an anagram of my name,” he says, moonlighting as Lyl Libido on The Well (Whole Earth ‘Lectronic Link), an early virtual community through which he interacted with journalists, writers, and online technophiles at a distance.

It wasn’t only the communication around Cyberpunk that made it such a portentous artefact of music’s history and future. The very production was as unique then as it is commonplace now, in having been recorded at home on a PC. “You did have a computer screen and everything, it was just very early. The Pro Tools machine was quite small in those days,” says Idol in an attempt to describe what his home studio looked like in 1993. “The ‘punk’ of cyberpunk was this whole DIY thing, so instead of recording in a studio, we brought the Pro Tools here and recorded in this other room that I’ve got. We did the drums, we did the whole album there at my house. It’s a radically different experience to the Charmed Life record—we made that and all the other records in serious studios. This was taking this idea that you could bring your music home. The next minute, that’s what people are doing. They’re all sitting at home. Recording,” Idol adds with a cackle. “That was really, really early on. It was the way music is being made today. Everybody’s making it at home. I don’t think my son goes into real studios.”

Top Left: Jacket BILLY’S ARCHIVE Shirt VINTAGE VIVIENNE WESTWOOD Boots CHURCH Rings MARIANNA HARUTUNIAN Top Right: Belt BILLY’S ARCHIVE Bottom: Hat, ring, and bracelet BILLY’S ARCHIVE

Idol’s aforementioned offspring, Willem Wolfe, along with daughter, Bonnie Blue, were still only toddlers when Cyberpunk was coming into being. It was a time that coincided with his coke and heroin habit famously getting out of hand. Reality, quite literally, hit Idol hard when he suffered a near-fatal motorcycle accident in which he almost lost a leg, a few years before the album was released. “I’d been in a hospital in 1990 for a month on the highest morphine ever. I sort of said to myself then, ‘Man, when are you ever going to be on something as strong, as pure, as this again.’ I was on this lockout, where every 12 minutes you give yourself a hit… You know, I’m a drug addict. So you say to yourself, ‘This is the highest point. You’re never gonna get this high. You’re chasing something that’s not going to happen to you again’.” Legend has it that music journalist and Punk magazine co-founder Legs McNeil inspired Idol’s new cyberdelic direction, having referred to the sight of an electronic muscle stimulator on his broken limb as “cyberpunk” during an interview. Thus began Billy Idol’s interest in the subculture surrounding computers and the internet. “It was just kind of fun to think about it. As opposed to, you know, how many records can I go on saying it’s fantastic being high and having sex with a million girls. It’s great, but how many records can you make like that?”

As a voice that emerged with the punk of the ‘70s—among The Sex Pistols, The Clash, and Idol’s own band, Generation X—that the grunge artists of the ‘90s had by then already started referring back to, Idol was interested in finding out what the next truly revolutionary sound was going to be. Evidently, it wasn’t the aforementioned guitar-heavy rehashes of a bygone era. “It’s 1993. I better wake up and be part of it,” Idol famously told The New York Times on the release of Cyberpunk. “I’m sitting there, a 1977 punk, watching Courtney Love talk about punk, watching Nirvana talk about punk, and this is my reply. It’s just my own way of saying, ‘Wooo! What about that? Hey, I’m Lollapalooza too! I’m the cyberpunk.’”

A lot of the pop culture that preceded Cyberpunk was uncannily prescient, touching Idol’s life personally and inevitably shaping what would later become the album. He was initially tapped to play the main antagonist in James Cameron’s classic Terminator 2: Judgment Day blockbuster, but his motorcycle crash ultimately prevented him from taking on the role. “There’s one bit where the T-1000 comes to life,” Idol explains. “Robert Patrick [runs] behind the car. I [had] this terrible limp, there was no way I could do it. It’s such a shame, because it would have been fantastic.”

Left: Jacket BILLY’S ARCHIVE Shirt VINTAGE VIVIENNE WESTWOOD Boots CHURCHS Rings MARIANNA HARUTUNIAN, Right: Coat and boots BILLY’S ARCHIVE Shirt VINTAGE VIVIENNE WESTWOOD Necklaces LOREE RODKIN and BILLY’S ARCHIVE

A cult classic and box-office smash when released in 1991, Terminator 2 and its story of an advanced ‘Skynet’ algorithm represent for many a foreshadowing of the potential dangers of self-aware artificial intelligence systems, who might eventually view humanity as a threat. “People are scared of AI and everything. The robots are gonna take over. And, yeah, a lot of it is going to happen. They’re creating robots that sweat. It’s just like The Terminator. In fact, Jim Cameron even said, ‘I warned you,’ the other day. And I went, ‘Yeah, you fucking did!’ They’ve probably got Skynet going now.”

The same could be said for Cyberpunk. In drawing from the fragmented and expansive underworld of ‘80s and ‘90s internet culture, the album is its own futuristic time capsule of people, ideas, and references; social conditions and contexts still relevant today. On ‘Neuromancer’— named after Gibson’s 1984 novel—Idol growls “Only from space, can you see/ How much earth is burning,’ as Mark Younger-Smith’s glam rock guitar sweeps over producer Robin Hancock’s funky acid house production. “Back then, you couldn’t see the Amazon burning from space,” Idol laughs, referring to those 1993 lyrics of prophetic doom. “And when we talk about toxins and the way the climate is, there’s the ‘toxins of my own demise.’ There’s all this stuff in it.”

In fact, in the same year that Idol released Cyberpunk, environmentalist and then-vice president Al Gore was warning the world about climate change as temperatures soared in the US. “The majority of scientists have been telling us for years that the long-term warming trend greatly increases the odds that any given year will produce a much larger number of 100-degree days,” Gore told NBC talk show Meet the Press. “And that trend has been borne out over the last several years. We’ve seen records broken with regularity.”

Left: Rosary BILLY’S ARCHIVE Right: Jacket VINTAGE JEAN PAUL GAULTIER FROM BILLY’S ARCHIVE Sunglasses and hat BILLY’S ARCHIVE

At the same time, the peak hedonism of the ‘80s, as Idol sees it, had given way to the sobering realities of the crack cocaine epidemic and the rise of heroin chic. Even Cyberpunk touched on the latter with its new beat cover of The Velvet Underground’s controversial avant-garde folk number ‘Heroin.’ That was just one reality in a collision of many that made the album such a fabulously important artefact of popular culture. “In ‘82, AIDS was starting to be around but it hadn’t really infected everything until the ‘90s, until Magic Johnson got it,” Idol explains. “That’s when it really kind of hit. That’s when everything ground to a halt. The free love sexual revolution thing that had been going on since the ‘60s was still going on in the ‘80s… but it was all coming to a grinding halt by 1992.”

As both a product of, and exception to, his time, Idol’s Cyberpunk is a testament to his battle with his own demons, as much as with the rest of the world’s. For all that, its notoriety as the forgotten failure of the Billy Idol catalogue should certainly be reassessed. “They were telling you without saying it: ‘you’ve got to be yourself,’” he says about the artists he grew up with and admired; people like Lou Reed and David Bowie. “Whatever you are, you’ve got to own it and be it, and that’s a little bit of what was happening with us, even in punk. We wanted our own version of it. We didn’t want to copy each other 100%… We were all influenced by The Ramones, where we all sped our music up, but at the same time, you looked beyond that. Like, ‘We’re going to be Generation X. I’m going to be Billy Idol. I’m going to find out who that is and put it into my music.’”

Jacket BILLY’S ARCHIVE

Talent Billy Idol

Photography Kristie Muller

Styling Shandra Dyani & Megan Kelley

Hair and make-up Mitzi Spallas

Production Justin Trevino

Photography Assistant Alicia Vasquez

Retouch Sam Retouch

Talent Management Laurence Freedman at Another Planet